Why Nobody Knows How Many Species Live on Earth

The Unseen Majority Still Awaits Discovery

Names were one of the first uses of language. Say apple, and every English-speaking person can conjure up an image of the fruit. So why is the species name not the most crucial label?

Standing in my backyard last weekend, watching a pair of honeyeaters dart between bottlebrush flowers, I wondered how many other species were sharing this small patch of suburban life with me.

The birds I could name, some of the plants too, but what about all those insects buzzing around, the microbes in the soil, the countless organisms I couldn't see?

As an ecologist with over four decades of research experience who taught undergraduates biodiversity, I should know how many species exist on Earth. My colleague Chris and I have spent countless hours discussing this question while doing fieldwork or, more recently, helping landowners restore native vegetation.

The truth is wonderfully humbling… nobody knows exactly. Not even a close approximation.

This uncertainty might seem shocking in our age of big data and precision science. But for a mindful sceptic, it opens up fascinating questions about how we understand nature.

Why did humans become so focused on naming things? What happens when we can't count something? And most intriguingly, what matters more than names when protecting biodiversity?

In this issue, I'll share insights from scientific literature and my personal experience about why ‘How many species on earth?’ remains unanswered and why that matters for everyone who cares about nature's future.

Whether you're studying ecology or want to better understand life in your backyard, this exploration will change how you think about species, science, and our relationship with the natural world.

Join me as we unravel this mystery and discover why sometimes the most important things about nature aren't the names.

How Many Species Are There on Earth?

This is a deceptively simple question that even experts can't answer definitively.

The truth is, nobody knows exactly, not even the scientists who dedicate their careers to cataloging Earth's biodiversity.

Their best guess?

Perhaps 9 million species, give or take a few million.

This uncertainty might seem strange given that taxonomists, the nerdy types who catalogue, classify and name species, have been at it for nearly 300 years, ever since Carl Linnaeus, the "father of modern taxonomy," developed our current system of scientific classification in the 1700s.

His elegant binomial nomenclature—giving each species a two-part Latin name—revolutionised how we organise life's diversity.

Today, scientists have formally named and described about 1.9 million species.

That sounds impressive until you realise it might represent only 20% of what's out there. For every species we've catalogued, four or five more could be waiting to be discovered.

‘But surely we've found all the big stuff?’ you might ask.

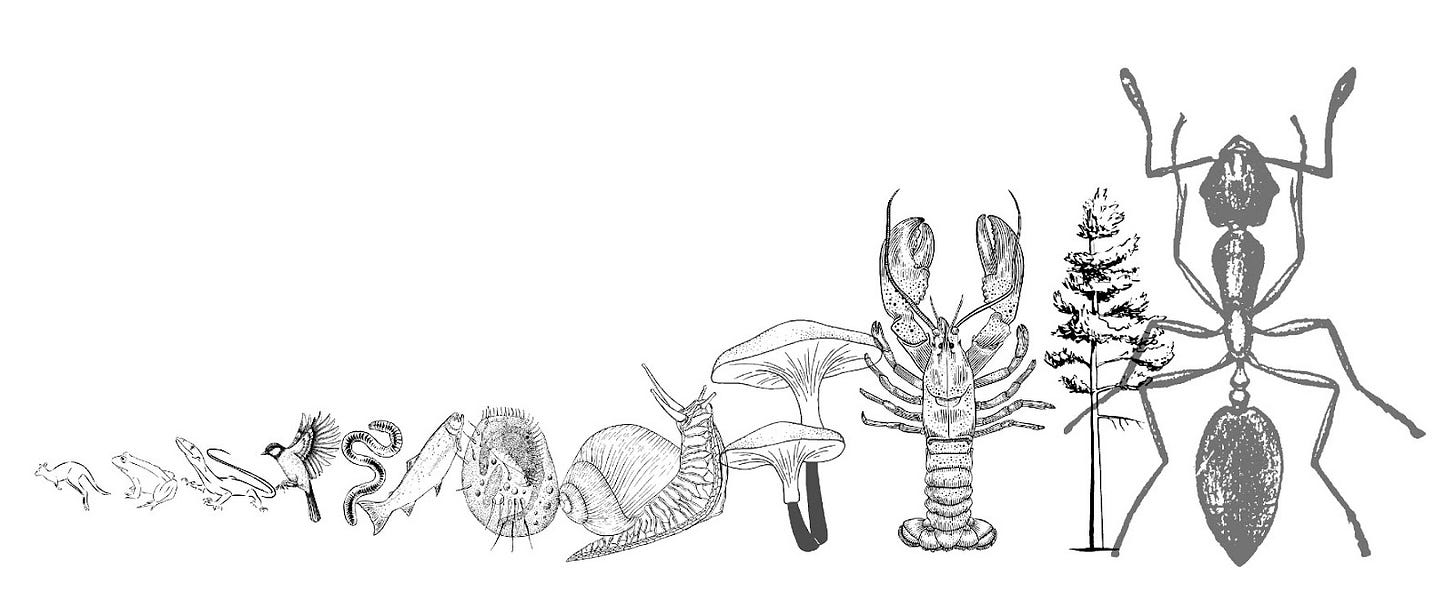

You're partly right. Most mammals, birds, and flowering plants are known to science. But we're still mainly in the dark when it comes to insects, other invertebrates, and microorganisms—the hidden bulk of Earth's biodiversity.

This knowledge gap has real consequences.

As my colleague Chris and I often discuss, you can't protect what you don't know exists. When a forest is cleared or a reef bleaches, we might lose dozens of species before we even know they existed. It's like having rare books burn in a library before anyone can read them.

Back to that question.

How many species are on earth?

Because we still don’t know how many species are on the planet. It makes lamenting the loss of a single species harder, given that there might be a dozen disappearing nameless for every named species that goes extinct.

The scientific species name

I’m guessing most people will know at least one Latin name for a species, maybe Panthera leo, Canis familiaris, Pan troglodytes, Orcinus orca, Homo sapiens, Platyarthrus hoffmannseggii… well, maybe not the last one, a tiny woodlouse that lives in ants nests.

Maybe you only know that Homo sapiens, ‘wise human,’ the primate species to which modern humans belong.

I do know that no one person knows all 1.9 million species with a description and a species name.

So, let’s do some historical digging.

Carl Linnaeus (1707 – 1778), the "father of modern taxonomy", was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician who formalised the modern system of naming organisms. Although what we now call binomial nomenclature was partially developed by Gaspard and Johann Bauhin almost 200 years earlier, Linnaeus was the first to use it consistently.

Linnaeus took long, complex names, such as "Physalis annua ramosissima, ramis ankylosis glabris, foliis dentato-serratis", and condensed them into "binomials", composed of the genus name, followed by a specific epithet for the specific name.

The genus and the epithet combine into the name of the species.

The complex long name becomes a simplified species name Physalis angulata that identifies a herbaceous, annual plant belonging to the nightshade family Solanaceae with the common name Wild Gooseberry.

Binomials became the standard label to refer to the species. The scientific name became the international code of nomenclature understood everywhere, where the first letter of the genus name is always capitalised and the whole binomial italicised. The system of binomial nomenclature with a genus name and specific epithet meant more than just a name; it was also the basis of a simple and orderly classification system.

Linnaeus published these new names and classifications in a book. The first edition of Systema Naturae, published in 1735, was just 12 pages, but by the time it reached its 10th edition in 1758, it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants.

Work on the 12th edition became so complex that Linnaeus needed a new invention—the index card—to track classifications and the names of animals and plants.

Today, 250 years later, taxonomists still use binomials in taxonomic zoological nomenclature to give each species a formal scientific name for some 1.9 million species to date—too many species for one book.

But there is still a lot of work left to do.

The catalogue remains incomplete despite all the hard work of taxonomists and natural historians over the centuries.

The task is daunting, and periodically, there are calls for more resources and expertise to tackle the challenge of binomial names like this one from the Australian Academy of Science, asking for $824m to complete the catalogue of species in Australia.

Do we need the binomial nomenclature for scientific names?

The main reason for naming species is that names are unique, with each type of organism having only one scientific name presented in a common language no longer spoken. A unique name helps avoid confusion created by multiple common names, and everyone anywhere can know the scientific name because they are in Latin, standardised, and accepted universally.

Each species name has a formal description for that species tagged to a curated specimen, the type specimen.

The type specimens are preserved and curated in museums and herbaria. They are used to make formal descriptions of species, the raw material for classifying and understanding evolutionary relations among species.

At this point, a mindful sceptic’s antenna begins to twitch.

How exactly? And why species? What is a species anyway? What makes that level of classification the root? Didn’t Professor Dawkins say selfish genes delivered on natural selection?

I hear you.

What is a species?

It’s species because they are the organisms that humans can mostly see and therefore describe in attributes of size, shape, and colour in collected specimens and behaviour, phenology and sounds in the live versions.

Because the attributes can be described and given values, they can also be compared for similarity, a mechanism for determining differences. So, species are not the root of the evolutionary tree but a convenient and measurable root of the international code of nomenclature.

Another mindful question is, do we need to know names?

Chris was out on a property the other week helping a client improve the vegetation on their land. Two days of planting tube stock was a lot of work, and the owners, a retired couple who had spent their careers as public servants, were very grateful.

“Thank you for being here for two days,” they said. “We have learnt so much from you people. It’s been great”

I’ll let Chris take up the story.

“One of the things I said to her as we stood talking about this and that plant, giving names away like confetti, and we're looking at a plant that's covered in fruit, a cheese tree.

So we're talking about that and I said ‘look, you know, this is good stuff because really one of the least interesting things in here is the names of all the plants’.

She looked a little bemused so I said, ‘really the most important things here about how it functions. You know, one of the things we've done is put Lomandra on your stream because it's really unstable and that plant can help hold onto the banks, it's about what we get from it. It's about how it functions. That seed there will be eaten and spread by something and provide nourishment and it'll move the seed around and that's what we want. The cogs and wheels that turn rather than the names of the cogs and wheels’.

She got it straight away.

She said, ‘well that makes terrific sense. Yeah, I get that.’”

People who have come to land management or farming from another career get ideas like this easier than those brought up with all the conventions. What Chris said was critical, even if it made Linneaus turn in his grave.

Names are helpful, and the international code for scientific names is essential to build descriptions of the evolutionary tree, but in the real world, the function is critical. What the organism does in its habitat is what we really need to understand.

Binomial nomenclature does wonders for classifying and naming entities, especially species, but it doesn’t capture function.

And that is unfortunate.

Being a Mindful Sceptic on Scientific Names and the Scale of the Challenge

Knowing names through formal taxonomy is very useful for understanding evolution, the distribution of organisms, who hangs around with whom, and the rules that allow assemblages of species to gather and remain stable.

Chris and I favour inventories of biodiversity, which means naming entities, usually species. It’s a shame that function is not part of the binomial.

But it is a momentous task.

A push for taxonomy gets to the heart of modern biodiversity science. Yes, we need to continue the crucial work of discovering and naming species. However, we must also understand how they fit into the more extensive web of life including their functions, relationships, and roles in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

As mindful sceptics in ecology, we recognise the importance and limitations of taxonomic work. The binomial system is essential for scientific communication and understanding evolutionary relationships. But it's just one piece of the puzzle in understanding and protecting Earth's remarkable biodiversity.

So next time someone asks you how many species there are on Earth, you can tell them the honest answer is we don't know exactly. And when they grimace at you, say, “No worries, exploring uncertainty is one of biology's great adventures.”

And while we continue discovering and naming new species, let's remember that knowing a species' name is just the beginning of understanding its place in the magnificent tapestry of life.

Mindful Momentum

The Field Guide Challenge

Next time you're outside, pick one small area—maybe a garden bed or patch of park—and try to count every living thing you can see.

Don't worry about names yet; just notice differences in form and function. What pollinates what? Who eats whom? Keep a simple journal noting how many different organisms you spot and what they do.

After a week, research the names of three species that intrigued you most. You'll start seeing the difference between naming nature and understanding how it works.

If you prefer, try this one…

The Ecosystem Story

Choose one familiar species—your backyard bottlebrush tree or local magpie—and spend a month building its relationship web. Watch who visits it, what parts they use, and how it changes with weather and seasons.

Draw a simple map showing connections to other species.

This shifts focus from "What is it called?" to "What does it do in the ecosystem?

Key Points

Humanity has only catalogued and named about 1.9 million species - potentially just 20% of Earth's total biodiversity. While most large, visible species like mammals and birds are known to science, most undiscovered species are likely insects, invertebrates and microorganisms that form the hidden foundations of Earth's ecosystems.

The binomial naming system developed by Linnaeus in the 1700s revolutionized how scientists classify and communicate about species. However, this focus on naming and categorising organisms misses something crucial - their ecological functions and relationships. Understanding how species interact and contribute to ecosystem processes is often more important than their formal scientific names.

The challenge of cataloguing Earth's species remains immense, with efforts like the Australian Academy of Science requesting $824 million to complete their national species inventory. This knowledge gap has real consequences for conservation, as species may go extinct before we even know they exist. Yet the sheer scale of biodiversity means a complete catalogue remains an elusive goal.

A mindful sceptic's approach recognises that while scientific names and classification are essential tools, they're just one piece of understanding biodiversity. The focus should expand beyond naming to include how species function in ecosystems, their relationships with other organisms, and their roles in maintaining Earth's life support systems. This fuller perspective is essential for both studying and protecting nature effectively.

You Might Also Like

Curiosity Corner

This issue of the newsletter is all about…

A mindful sceptic asks what something is called and what it does—a crucial shift in perspective that could transform how we understand and protect Earth's biodiversity, most of which remains undiscovered.

Here are 5 better questions that emerged as I reflected on what matters in species conservation:

What happens if we flip our whole approach and ask what a species does rather than what to call it? This question is better because it challenges our centuries-old obsession with naming and classification, inviting us to see nature as a beautiful web of interactions rather than a catalogue of Latin labels.

If not even experts can count all Earth's species, how do we know what we lose when habitats disappear? This one is good but also a bit of worry as it points to the heartbreaking reality that we're likely losing species before we even meet them, like burning books we never got to read.

Why do we find remembering scientific names easier than understanding ecological relationships? From my years teaching ecology, I've noticed how we often substitute memorising content for genuine understanding and this question helps us examine that peculiar human tendency.

When we restore landscapes, should we focus more on rebuilding functions than replanting specific species? This builds on Chris's profound insight with the retired couple - it challenges us to think like ecosystem engineers rather than taxonomists.

How might our conservation strategies change if we viewed species through their roles rather than their rarity? This is especially powerful because it suggests a fundamental shift in how we approach biodiversity protection, moving from a museum mindset to an ecosystem perspective.

Each of these questions pushes us beyond just naming things to understand how nature works—they're the kind of questions that could transform how we protect our living world.

What do you think?

Which one resonates most with your experience of nature?

In the next issue

Beyond the Climate Fix

235 million new humans. Three years. One planet.

While politicians promise climate solutions will save us all, population growth alone adds emissions equivalent to three European nations.

Discover why fixing the climate is just the beginning of our sustainability journey.

Sometimes the most valuable thing we can offer isn't another solution, but better questions.

If this exploration left you more curious than certain, more aware of complexity than convinced of simplicity, then something important just happened. That's mindful scepticism in action.

Your support ensures that I can continue to ask the awkward questions and follow the evidence to all the uncomfortable places it leads.

And for that, I need caffeine.

Lovely meditation on human ignorance, John! 👏

I like your "What happens if we flip our whole approach and ask what a species does rather than what to call it? " Assigning a name is about us. Describing function is about the thing itself.