What causes extinction?

The one word that explains why species vanish forever

Extinction is forever, and there is more of it happening just now than normal, making ‘what causes extinction’ a crucial question.

You'll never see a dodo waddle across your path or peck curiously at your shoes. Neither will your children, their children, or anyone else who will ever live on this Earth. When the last dodo drew its final breath somewhere around 1662, it marked more than just the end of a peculiar flightless bird. It became a powerful symbol of how quickly humans can transform the world around us.

As an ecologist who's spent decades studying how species adapt (or don't) to environmental changes, I've learned that contemplation of extinction is a window into understanding humanity's relationship with the planet we call home.

This week's Mindful Sceptic issue features an edited excerpt from The Mindful Sceptic Guide to Biodiversity Loss.

Several myths are busted in this book, but this one is a doozy.

I'll share a single word explaining why species go extinct. It's not ‘humans’, ’climate’ or ‘habitat’, although all these play their parts. Understanding this concept will transform how you think about biodiversity loss and give you a clearer perspective on our environmental challenges.

You'll learn…

Why extinction is both more straightforward and more complex than most people think

How evolution and adaptation work (hint: it's not what your textbooks might have told you)

What the dodo's story reveals about our current environmental predicament

A practical framework for thinking about species loss in the modern world

Let’s apply some mindful scepticism to one of the most misunderstood phenomena in nature.

Raphus cucullatus

Nobody alive has seen a dodo, the flightless bird endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean.

Nobody knows what this giant pigeon looked like. It’s been a long while since the last widely accepted sighting in 1662, and the descriptions and drawings are hard to verify. Many were made by illustrators who had never seen the animal.

Dodos had not seen humans either and had no fear of them, but there is no evidence that sailors plundering populations for provisions sent them to extinction. Nor was it likely that the resident humans on the island, which never exceeded 50 people in the 17th century, ate them to death.

However, people cleared much of the dodo's forest habitat. They also introduced alien animals to the island, including dogs, pigs, cats, rats, and crab-eating macaques, which plundered dodo nests and competed for limited food resources.

Nobody knows precisely what happened.

We know the species was probably extinct a century after Dutch sailors first reported it in 1598. Indeed, when the Dutch left Mauritius in 1710, the dodo and most of the large terrestrial vertebrates on the island were gone.

So, what causes extinction?

There is a one-word answer, but before we reveal that, let’s examine evolution and when extinction occurs.

All organisms evolve

The dodo was well suited to pre-human life in Mauritius. We know this because it existed as a distinct species to be seen by the intrepid explorers in their wooden ships from far away. It had evolved into its shape, behaviours and habitat over thousands of generations from a slightly different-looking ancestor.

The dodo's ancestors varied in anatomical, physiological, and behavioural attributes generated through genetic mutation and drift.

Some of these attributes were beneficial, and some were hindrances. Benefits are called adaptations to the environmental conditions in which an organism finds itself, which give the individual a better chance of survival, growth, and reproduction. Indeed, a benefit in evolutionary terms only occurs if the individual successfully reproduces.

How much help future generations get from a mutation depends on the environmental conditions and if those conditions are stable relative to the benefits the new attribute brings.

The dodo was flightless.

It had stubby wings, too small to lift the bulky animal off the ground. If the ability to fly offered no advantage to survival, growth or reproduction over not flying, then a mutation that made wings smaller had as good a chance of propagation as fully functional wings.

Meanwhile, if a large body and a big beak gave foraging advantages and no penalty for not flying, before long, dodos without expensive wings and flight muscles had the advantage. Biology sees no need to build and maintain unnecessary structures.

Individuals carrying the genes for functional wings were disadvantaged, and natural selection weeded them out.

It is cruel like that.

Here is another example.

Suppose a tree species evolves a mutation that allows seedlings to survive longer when the soil is dry. This might be a considerable benefit if the climate is warming and the soil dries out faster between rain events.

A mutation for more robust seedlings allows for regeneration and buys some time for future generations of the tree to track habitat change as warmer, drier conditions spread across the landscape.

If the climate changes to colder and wetter, the mutation may have no effect or even be a disadvantage.

When does extinction occur?

Extinction happens when the last individuals of a species can no longer reproduce unaided.

The last lone rhino without a mate might persist for a few decades, and the species is extinct when it dies. The species is extinct when the remaining individuals can no longer reproduce.

Failure to reproduce comes about through

death before reproduction, a failure to survive because the conditions were too severe or the food, water or nutrients were lacking for whatever reason, from competition to a tsunami

insufficient food or nutrients to either grow to reproductive size or channel resources into gametes or both

absence of the necessary gametes, again for a range of reasons from failure to find a mate to a shortage of pollinators

Failure to reproduce for the last remaining individuals is the point of extinction.

Failure to reproduce is about individual organisms' survival, growth, and reproduction. Enough individuals must achieve successful reproduction for the species to persist.

This basic premise applies to everything from microbes to marsupials.

Extinction happens when an organism's ability to gather sufficient resources is compromised to the point that all the remaining individuals fail to reproduce.

What causes extinction in the specific sense is the failure of all remaining individuals of a given species to gather enough resources to survive, grow and reproduce—the specific failure depends on the species and the circumstances.

Extinction is much more likely when the species is rare, has a restricted distribution, or both. The dodo on Mauritius had a restricted distribution and became rare when humans altered its habitat and introduced animals to the island that were unfamiliar predators.

Extinction is also likely when environmental conditions change sufficiently to compromise the ability of individuals to reproduce.

Should environmental conditions change dramatically from what is usual, for example, a human being comes with an axe and chops a bunch of trees down, this is a disturbance outside the norm in terms of extent and intensity. Many organisms are pushed outside their comfort zone and struggle in new conditions.

Any remaining individuals have only three options.

Hunker down in whatever safe place they can find, hoping the disturbance disappears and normality returns.

Move to the nearest patch of intact forest; easy for an eagle, but challenging for an orchid or a dodo.

Die

Adaptation through genetics happens relatively slowly, and extinction occurs when the environment no longer suits the evolved adaptations. So, we are close to the one-word answer to what causes extinction.

I'm just stringing it out a little longer for dramatic effect.

Look at this image from Western Australia that shows an intact eucalyptus forest and a forest cleared for agriculture. Now, it doesn't take a genius to work out that the conditions on one side are very different to those on the other.

Many organisms that exist in the three-dimensional conditions of the forest—places to hide, food to eat, shade from the sun—would struggle to find adequate conditions in the agricultural field.

Figured it out yet?

What causes extinction?

The one-word answer is

disturbance

Specifically, it is a disturbance that alters conditions beyond the tolerance of a species' last remaining individuals, preventing them from reproducing.

Right now, disturbance is everywhere.

In the last two hundred years, humans have harnessed fossil fuels through machinery to transform the landscape radically. Vegetation is cleared and managed, and the organisms that were part of a slow, subtle change from predictable, natural disturbance can no longer cope. Humans have brought about radical, intense, and acute changes.

People can sound incredulous and surprised by this reality, but it shouldn't be surprising. If we disturb such a large proportion of the landscape with axes, chains, fire, and tractors, then we know that we will lose organisms from that landscape.

Any surprise we have at biodiversity loss is misplaced—it shouldn't be a surprise at all.

Biodiversity loss through local and global extinction is an inevitable consequence of human beings acquiring resources and making humans the priority. As we channel nature to our purposes, humans disturb almost everything.

Disturbance causes extinction

Before we get all high and mighty or anthropocentric about disturbances, remember that they have happened at a global scale many times before.

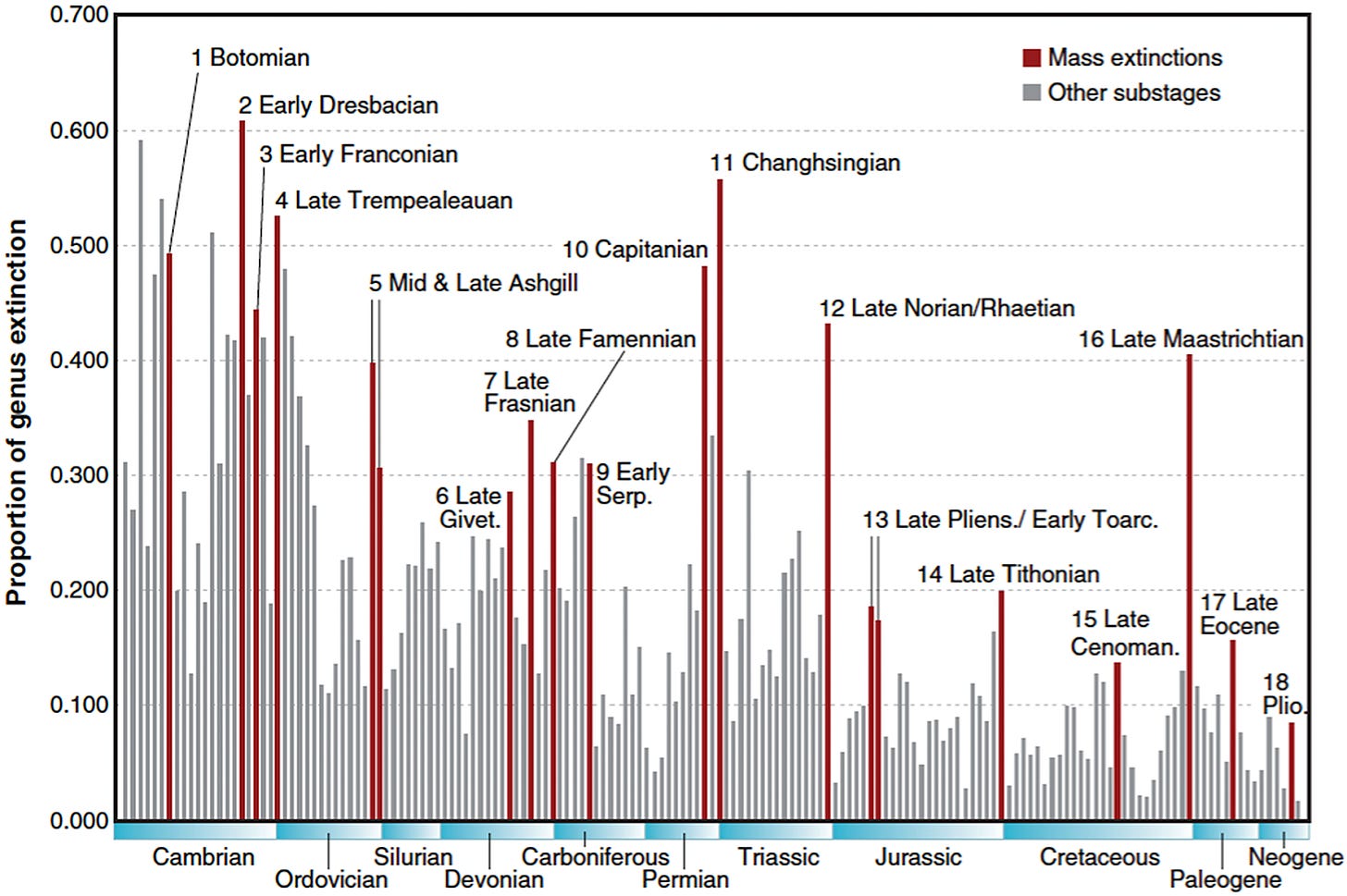

Human-induced mass extinction is at least the sixth big one, and numerous small global extinction events are evident in the fossil record.

Most of them are attributed to climate change, especially ocean warming. Even the famous meteorite strike that created the boundary between the Cretaceous and Tertiary approximately 66 million years ago, which took out the dinosaurs, caused a climate disturbance.

Most of those creatures didn’t die in the blast but starved when the dust in the atmosphere shaded the sun and messed with the plants.

Disturbance is what causes extinction, and disturbances happen all the time.

The current human one is not unique. Nor is it immoral because it is inevitable; it is simply a consequence of adaptation… human adaptation.

Disturbance

Disturbance causes extinction, and the planet is currently disturbed by human activity, specifically activity in the last 200 years.

Extinction can be sad for us. It is tempting to focus on losses as preventable events and a bad thing with a cause and someone to blame. But if disturbance is what causes extinction, then it is going to happen because of what Homo sapiens, the species, has become.

Not only are we swallowers of exogenous energy and able to bend the environment to our own needs, but we are also abundant.

Our challenge is not extinction but to cope with the consequences of rapid population growth. And when we say rapid, we mean rapid to levels that historically, not even Thomas Malthus would have believed possible.

But here we are at 8 billion, with 8,000 extra people added every hour. With this many people, disturbance is inevitable.

Dip into our groundbreaking series, which transforms dense environmental science into compelling narratives. The Mindful Sceptic Guides empower readers to navigate the complexities of our changing world by combining the objectivity of scientific scepticism with the wisdom of mindful awareness.

There is even one on population!

So we shouldn't be surprised by extinction. If 50 people on a 2,000 km2 island and a few visitors in wooden boats can push a flightless bird to extinction, what are 8 billion humans with container ships going to do?

It is time to become more pragmatic about our rhetoric around loss.

Accept it for what it is. Then, make some very tough but essential choices around what types of biodiversity we want to keep and, therefore, what effort it will take.

So don't be surprised when species go extinct.

Be sad, disappointed, and somewhat ashamed that we haven't been able to fix this problem or manage our use of the planet more effectively.

However, we must recognise that humanity faces a monumental challenge with both pessimistic and optimistic outcomes. As we disturb the planet to its sixth mass extinction, remember that extinction is a risk humanity faces.

We have to ask awkward questions, especially this one…

How much disturbance and extinction can we tolerate before it starts to impact our likelihood of survival?

Mindful Momentum

The Habitat Detective Challenge

Choose a small patch of nature near you, perhaps a corner of your local park or garden.

Visit it weekly for a month, spending 15 minutes carefully observing and documenting the life you find there.

Note the plants, insects, birds, and any changes you see.

Then, introduce a slight, controlled disturbance (like trimming one plant or moving a log) and observe how this changes the mini-ecosystem.

This hands-on experience helps you understand disturbance and adaptation at a micro-scale.

Key Points

Extinction occurs when the last individuals of a species can no longer reproduce successfully - a biological endpoint that's both simple and profound. While individual causes of extinction can vary, from habitat loss to climate change, they all represent forms of disturbance that push species beyond their ability to adapt. Understanding this fundamental principle helps cut through the complexity of biodiversity loss.

Historically, disturbance has been a natural driver of evolution and extinction, from asteroid impacts to climate shifts. However, human activity in the past 200 years represents an unprecedented scale and speed of disturbance, transforming landscapes and ecosystems faster than most species can adapt. This accelerated change, powered by fossil fuels and population growth, drives what scientists recognise as the sixth mass extinction event.

The dodo exemplifies how even relatively small human disturbances can lead to extinction. On Mauritius, a population of just 50 people, along with introduced species and habitat changes, was enough to eliminate this unique bird within a century. This case study demonstrates how species with restricted distributions or specialised adaptations are particularly vulnerable to disturbance.

Rather than viewing extinction as a series of preventable tragedies, a mindful sceptic understands it as an inevitable consequence of human development and population growth. This perspective shifts focus from attempting to prevent all extinctions to making conscious choices about which species and ecosystems to prioritise for conservation. The key question becomes not how to stop disturbance entirely but how much disturbance human societies can create before threatening their survival.

You Might Also Like

Curiosity Corner

What this issue is about…

In a world where 8 billion humans transform landscapes at unprecedented speed, understanding extinction through the lens of disturbance helps us move beyond blame to make pragmatic choices about conservation.

1. "How fast is too fast?"

Instead of asking whether extinction is natural (it is), we might ask about the speed of change. If adaptation through genetics happens relatively slowly, what's the threshold between disturbance that drives evolution and disturbance that drives extinction? This reframes the extinction debate around rates of change rather than just the changes themselves.

2. "What do we mean by 'preventable'?"

Rather than asking how to prevent extinction (which may be impossible), we might ask what we mean when we call an extinction preventable. The dodo shows us that even small human populations can trigger extinction, so is delaying extinction the same as preventing it?

3. "Which adaptations become disadvantages?"

Instead of listing endangered species, we could ask which evolved traits—like the dodo's flightlessness or modern species' specialised diets—might become disadvantages under rapid environmental change. This would help us understand vulnerability patterns rather than just documenting decline.

4. "How do we measure disturbance resilience?"

Rather than simply documenting disturbance, we might ask how different species and ecosystems absorb and recover from it. What makes some species more resilient than others? This shifts focus from preservation to understanding adaptive capacity.

5. "What is the human cost of extinction?"

Instead of viewing extinction as a conservation issue, we might ask how the accumulation of extinctions could affect human survival. At what point does biodiversity loss compromise the ecological services we depend on? This connects extinction to human self-interest rather than just environmental ethics.

In the next issue

Breaking All The Rules with a Story of Woodlice and Wisdom

What happens when you hand university students some woodlice and tell them to figure it out? In our next issue, discover how throwing away the traditional teaching script revealed surprising truths about learning, scepticism, and the courage to question everything.

If this analysis helped clarify a complex issue or challenged your thinking in productive ways, I'm grateful you took the time to engage with the evidence.

Creating well-researched content that cuts through environmental spin takes considerable time, courage and coffee.

If you found value in this mindful sceptic approach, consider supporting the work with a virtual brew.

Good presentation, John! 👏 Humans are (so far as we can tell) the only species that can understand when its behavior is threatening to destroy most/all of a species, has some degree of "choice" about doing that, and largely decides "Meh. No big deal. Let's keep on going". A minority of humans can feel compassion for non-human beings (especially the non-cute variety) and grief at their annihilation (eco-depression). The rest view most living beings as an IT to be consumed rather than another center of consciousness. Given our population size and disruptive technologies, more extinctions than baseline are likely going forward.

"The Garden of Eden is upon the Earth, but people will not see it". -- Joseph Campbell