Why you need scientific authority

When Science Shapes Our World And Why It Matters

Scientific authority means a lot to you. You may not know this or you do and take it for granted. Some are even in denial about science when it is time to accept the power of legitimate science for crucial decisions we need to make.

We're all scientists now, whether we realise it or not. We live in a world built by scientific authority, from the smartphone alarm that woke you this morning to the carefully engineered coffee that helped you start your day.

But here's the fascinating part and why this matters deeply to you. While we readily trust science for weather forecasts and headache tablets, we often struggle when scientific evidence challenges our beliefs about more significant issues like climate change or biodiversity loss. And heaven help you if there is a value involved.

As someone who's spent decades straddling academic research and practical environmental solutions, I've seen how this tension plays out in universities, the civil service and especially commerce.

Whether you're a student trying to navigate an overwhelming flood of environmental data or a concerned citizen working to make informed decisions about your community's future, learning when and how to accept scientific authority is becoming an essential life skill.

In this newsletter, we'll use mindful scepticism to develop this balance, helping to…

Cut through information overload to find reliable evidence

Recognise when (and why) to question scientific claims

Make confident decisions about complex environmental issues

Bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and practical action

Think of this as your guide to becoming a more discerning consumer of scientific information—without losing your mind or your curiosity in the process.

Confidence in science

The device that brings you this issue of Become a Mindful Sceptic is a product of science. As is the paracetamol tablet you took for that nasty headache that just melted away, not to mention my hip replacement surgery.

Science also helps you get the $5 burger from your favourite outlet. The supply chain that delivered that morsel of deliciousness is up to the cow’s eyeballs in technology.

Yes, folks, the scientific method is not just used by geeks.

All of society, from health professionals to toothpaste manufacturers, uses science and the evidence it generates.

The scientific method—in its common form, the logic of hypothesis testing through experimentation—is the best way to find out what works and what does not. This allows knowledge to make leaps that would take too long by trial and error and to explain how nature works, especially for our benefit.

An advantage of presumption from this understanding is that we don’t always have to start from scratch whenever we need a solution to one problem or another. Modern engineers use a pile of laws of nature that were first figured out by the likes of Galileo, Newton, Einstein and their mates, all scientists. What these authoritative fellows and those who followed discovered made it easier and safer to construct buildings, railways, bridges, ships and eventually rockets that made it to Mars and beyond.

Undoubtedly, the Industrial Revolution was about energy, coal and then oil, and the mobilisation of capital that became possible on the back of it, but science gave the revolution impetus.

Science helped us understand and tackle the COVID-19 pandemic and will help us with the next one. Science helped create your car, your phone, the wi-fi signal in your house, the streaming service you enjoy so much, the microwave oven, the uniform colour and size of the capsicums in your fridge, not to mention the milk.

Who knows where the fundamentals applied to technology will take us next?

In short, science matters to us all.

Some practical examples

I recall a in one of my ecology classes two students were in a heated debate on how to evaluate competing claims about local wetland restoration. I was always excited when this happened. I would pat myself on the back and pretend I was doing something right.

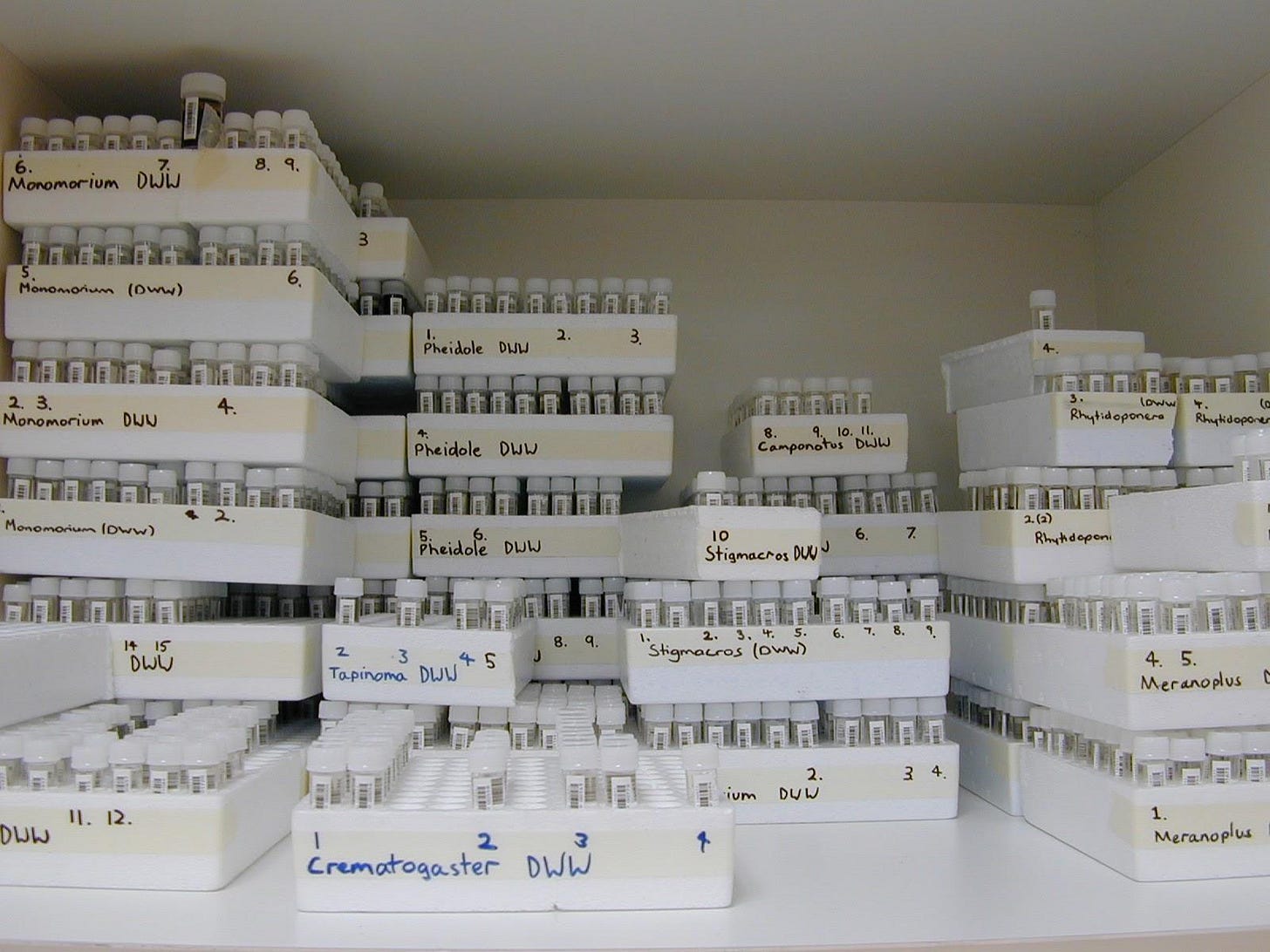

One student had sourced a systematic review of 50 similar projects, while another shared dramatic before-and-after photos from a single site and a copnversdation they had with the landholder. The visual evidence was compelling in the ‘worth a thousand words’ way but the dense systematic review—a comprehensive research study that methodically identifies, evaluates, and synthesizes all available research on a specific question using predetermined criteria and protocols to minimize bias and provide reliable conclusions—had way more evidence.

Resolving the debate required evidence evidence hierarchy thinking because not all evidence is created equal. Some is weak and some immutable. The skill is understanding what you have and evidence hierarchies help making the call.

We will look closely at hierarchies in later newsletters but to resolve the debate between my students, I simplified the hierarchy to…

Systematic review—multiple sites, peer-reviewed methods, controlled comparisons

Single case study—compelling visuals but limited scope

Local anecdotes—important context but lowest evidence tier

The students used this framework to resolve their conflict. Anecdotal and visual evidence was useful but the value came from repeated application of the scientific method compiled into a review.

Here are a few more claims that need some mindful sceptic questions to determine their scientific authority

Tree planting reduces urban temperatures by 2-4°C

What tree species were studied?

Over what timeframe?

In which climate zones?

What about maintenance costs?

Reusable bags are better for the environment

Life cycle analysis data

Production energy costs

Actual reuse rates

Local recycling capacity

Alternative energy solar farms are more environmentally friendly

Check energy output claims against local weather data

Compare habitat impact studies

Review community benefit calculations

Examine maintenance requirements

Scientific authority has become part of the furniture

The authority of science has been an important part of how Western culture has developed.

Indeed, it is tempting to cede authority to scientists, given they generate and have the facts, the scientific knowledge. Plus they have the training to interpret the facts into evidence. They know what the average Joe cannot.

Joe is more than happy to defer to the scientific authority when this evidence is about how to send a rocket into space and predict the weather from data beamed back down from the satellite that the rocket deposited up there.

It makes sense; he cannot know it on his own, and he verifies the evidence every day he forgets to take his umbrella to work.

Where evidence has solidified into the laws of physics that work and align with common sense, ‘drop an egg, and if it falls onto the floor tiles it will break’, these laws that science generates are immutable to even the sternest sceptic.

We will never understand some scientific authority, especially evidence not yet consolidated into a natural law, and this is easily ignored without too much of a problem. Quantum mechanics, we don’t need to know how it works. Whatever happens in the world of tiny particles, it doesn’t matter as long as the egg breaks when it’s dropped on the kitchen floor or doesn’t when eased gently into the frying pan.

The reality is that some science has to be taken on faith by the non-specialists, those not trained in the intricacies of the method. This is a good reason why the logic of the scientific method has to be on every high school curriculum and taught well so that the approach is understood. Even if I don’t understand algebra or know one tail of a bell curve from another, I can understand the logic of the scientific method and be confident of the outcomes that scientists tell me are likely.

All I have to do is make sure the scientists with the evidence have followed the scientific method—they have authority.

A public ceding authority to an agreed process makes more sense than giving it up to an individual, especially when the process is tried and tested and delivers so much technological progress. And this is what has happened. We even invented and built scientific institutions to house the scientific community and our trust in science. Almost everywhere and for much of the time, scientific authority is a given: a comfy leather chair with a remote perched on its smooth arm.

If only the real world were so comfy.

Values trump authority from research

Suppose a science nerd comes along and, with only objective intention, wields the power of scientific authority and tells me that if I convert the 5,000 ha of virgin forest to a palm oil plantation, it will destroy biodiversity and many vital ecosystem services, not to mention the addition of millions of tons of carbon to the atmosphere.

I might not be so happy accepting his authority if I stand to make a handy profit from the palm oil.

Likely, I will trump his scientific claims with my economic ones.

In the blink of an eye, we are into values territory, and this is not an argument over evidential authority but one of opinion and choice of moral authority.

This problem of competing values is at the root of much science denial. Sometimes, we don’t like what evidence tells us.

The chance to spin

Science is good at evidence. Done well, science is very good at it, but there will always be uncertainty around any evidence generated and how that evidence is interpreted. The laws of nature hold as far as we know, but they only easily explain some of the attributes and behaviours of complex systems with any certainty.

Nature is massively complex, with myriad organisms interacting with each other and the environment, generating patterns and attributes that can look like randomness. This makes full, fearless explanations difficult. It is why you will often hear a scientist sitting on the fence, unable to give a definitive answer, yes or no. Systems exhibit patterns that can be described with a likelihood. They may happen today or at some time in the future, or they may not. Complex systems still hold many secrets from us.

Complexity is hard to pin down with the reductionist logic of the scientific method. And as soon as there is even a hint of hesitation, uncertainty or cause-and-effect connections break down, all bets are off.

A crack appears, and spin enters. Suddenly, the koala is going extinct before the end of the next election cycle, and the smart folk are out looking for black swans.

Typically, when spin is around, the evidence is corrupted, and the uncertainty in the wind makes denial inevitable.

Denialism

The denial of science and undermining of scientists is as old as science itself. Our modern examples of post-truth, alternative facts, and fake news sit alongside the biblical prophets, the church through the ages, and the need to believe in miracles.

It used to be that people questioned scientific authority because science is a head-on challenge to all faith-based religions and mysticism, the beliefs that gave people some stability and hope when times were tough, and the average citizen had no education and spent their time in a struggle to stay alive.

Denial of science was the prevalent paradigm until the Enlightenment. This period of history in the 1600s, also known as the Age of Reason, illuminated intellect and culture from the darkness of the Middle Ages through concepts such as reason, liberty and the scientific method.

You can sum up the logic from the processes in science that gave us the Age of Reason fairly simply.

Why fight over religion?

It must be more enlightening to voyage far and wide to discover the world and use deduction—the scientific method—to look into how the world works with the singular motive of truth. Surely, this is better than the ‘bible tells me so’ explanation.

Enough people thought this way to go against the mainstream and question the traditional thinking that mainly came from religious texts and the culture built around them. In time, what they found out changed the mainstream.

Applied correctly, deduction through the scientific method generated facts and put facts together into evidence. The world became round, revolved around the sun, and many of nature’s wonders were understood.

The accumulation of facts generated authority and with it the ability to influence others. In 1947, the German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber defined authority as ‘power wielded legitimately’, bestowing some moral high ground on influence. In reality, the ‘facts’ were handy if you owned the coal mine or the shipyard that could now build vessels made of steel and powered by steam. Not only could you take dominion to the next level, you could make money.

However, there is more to modern science denial than a challenge to our deep dependency on deities or the economic corruption of objectivity.

Contemporary science deniers have not one (religious) motive but many—greed, fear, bias, convenience, profits, politics—to which they cling with various degrees of sincerity and cynicism.

Robert P Crease

This great quote from Robert Crease comes from an article talking about his book The Workshop and the World: What Ten Thinkers Can Teach Us About Science and Authority Robert P. Crease, W. W. Norton (2019)

A mindful sceptic suspects that the motives he lists are very powerful.

They extend the religious imperatives to the psychology of the individual. Here, we deal with fear, ego and insecurity, a heap of negative energy in the world that manifests in motives of profit, politics and power.

If denial helps achieve the fruits of these motives, then it will happen, no matter how much science has provided to society. If scientific authority gets in the way of these powerful motives, it will be brushed aside, and denial is a handy and practical brush.

Being a mindful sceptic with scientific authority

Science and technology are the main reasons humanity has generated so much material success. It has helped us build technologies and any number of engineering solutions to improve our daily lives.

We use evidence from science to feed, clothe, shelter and power close to 8 billion souls and will need it more and more to keep these folk sufficiently resourced not to fight each other all the time.

Given all the obvious uses and benefits of science to society, what’s with science denial? Why deny the obvious? Denial of scientific authority makes no sense, given what it has done for us. It also makes no sense to deny science when faced with global and local problems that can’t be wished away but have to be solved.

A self-respecting sceptic readily accepts the power of legitimate science and uses the evidence it generates wisely, even recognising the cultural authority of science because it might just stop us from killing each other.

But a mindful sceptic knows that evidence is insufficient; scientific authority is inadequate. She knows that humans are at the mercy of their greed, fear, bias, convenience, profits, politics and the genetics that give us our lizard brains.

And nothing is more valuable than knowing that.

Key points

Science's reach extends far beyond laboratories and textbooks, touching virtually every aspect of our modern lives—from our morning coffee to space exploration. This ubiquitous influence often goes unnoticed, yet it fundamentally shapes how we live, work, and understand our world. It's not just about rocket science; it's about the everyday technologies and conveniences we take for granted.

The relationship between scientific authority and human values creates a fascinating tension in our society. While we readily accept scientific evidence for weather forecasts or smartphone technology, we often struggle when scientific findings challenge our deeply held beliefs or economic interests. This dynamic plays out in everything from climate change debates to local environmental decisions, revealing how personal values can trump even the most robust scientific evidence.

Scientific authority, while powerful, has inherent limitations when dealing with complex systems and human behaviour. Nature's intricate web of interactions often defies simple cause-and-effect explanations, which creates space for uncertainty and misinterpretation. This complexity, combined with our tendency to bend evidence to fit our preexisting beliefs, means that even the most rigorous scientific findings can be misused or misunderstood.

The path forward lies in mindful scepticism—a balanced approach that acknowledges both the power of scientific evidence and the reality of human nature. This means learning to navigate between blind acceptance and reflexive denial, understanding that while science provides our best tool for understanding the world, it must always be interpreted through the lens of human values, limitations, and biases. In essence, it's about being both critically minded and mindfully aware of the broader context in which scientific knowledge operates.

In the next issue

The Uncomfortable Truth About Environmental Solutions

Everyone loves a silver bullet. But what if our search for perfect solutions is part of the problem? Next week, we'll examine why the most popular environmental fixes keep failing, what cognitive biases blind us to better alternatives, and how being a mindful sceptic can help us embrace the messy reality of real progress.

Warning: sacred cows will be questioned