Why Everything We Know About Healthy Eating Might Be Wrong

The Evolutionary Mismatch Between Modern Dietary Guidelines and Human Metabolic Health

Here is Chris to tell you all about some dietary guidelines.

The hospital cafeteria serves low-fat meals with whole grains while patients recover from metabolic diseases on the upper floors.

School lunch programs follow government guidelines as childhood obesity rates climb.

Something doesn't add up.

How did we arrive at dietary recommendations that seem increasingly disconnected from both our evolutionary history and current health outcomes? What happens when we apply critical thinking and evidence-based analysis to challenge conventional nutritional wisdom?

This week's Mindful Sceptic offers you more than just another perspective on diet.

You'll gain practical tools for evaluating scientific claims, understanding how complex systems like human metabolism interact with modern food environments, and recognising when seemingly authoritative guidelines deserve deeper scrutiny.

As we examine the surprising disconnect between official dietary guidelines and human health outcomes, we'll draw on evolutionary biology, metabolic science, and population health data to understand why reaching a consensus on the "perfect" human diet remains so elusive.

Whether navigating campus dining choices or advising grandchildren about healthy eating, this mindful sceptic approach will help you cut through nutritional noise with greater confidence and clarity.

More importantly, you'll learn how to apply critical thinking skills to make more informed decisions about your nutrition in an environment of conflicting advice and commercial interests.

Let's begin by considering a startling reality…

For 290,000 of our 300,000 years as humans, we thrived without any official dietary guidelines.

The Modern Diet Paradox

Google ‘healthiest diet for humans’ and you will get over a million hits in less than a second.

Mostly plants, healthy grains, paleo, low-carb, vegan, Mediterranean…?

Do we actually know?

Let’s pretend for a minute that we are going to feed everyone in the world with the best diet. How would we inform that choice?

There is a range of authorities, (governments, dietitian associations, World Health Organisation, etc.) offering recommendations about what to eat. Most countries have some form of official dietary guidelines.

Many of the recommended diets include plenty of vegetables, fruit, grains, low-fat meats, and dairy. This is pretty common across wealthy countries, including all the countries on the chart below with a high average calorific supply. We could see this as the ideal as these countries have the resources to use science to determine the best diet, right?

Maybe, so why are obesity rates going through the roof in these countries? Rates are similar in these countries for diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

The US Food and Drug Administration clearly relates diet and disease:

“Each year, more than a million Americans die from diet-related diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes and certain forms of cancers. In 2020 alone, an estimated 800,000 people died from cardiovascular disease, an even greater number than the horrific toll of COVID-19 during that same year. And obesity, which is both a disease and a condition that increases the risk for other diet-related chronic diseases, has increased to historic levels in children and adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Ah, you might say, people are just bad and lazy, and they don’t follow the guidelines.

Well, maybe.

This is the official advice, so schools, hospitals, defence forces, nursing homes, and food programs for the poor follow it. It is also the advice most doctors will give their patients.

Maybe some are not following the guidelines, but many are. Having a choice of what to eat is a luxury not enjoyed by many in the global south. Even in wealthy countries, we know that diet-related disease increases as incomes decline.

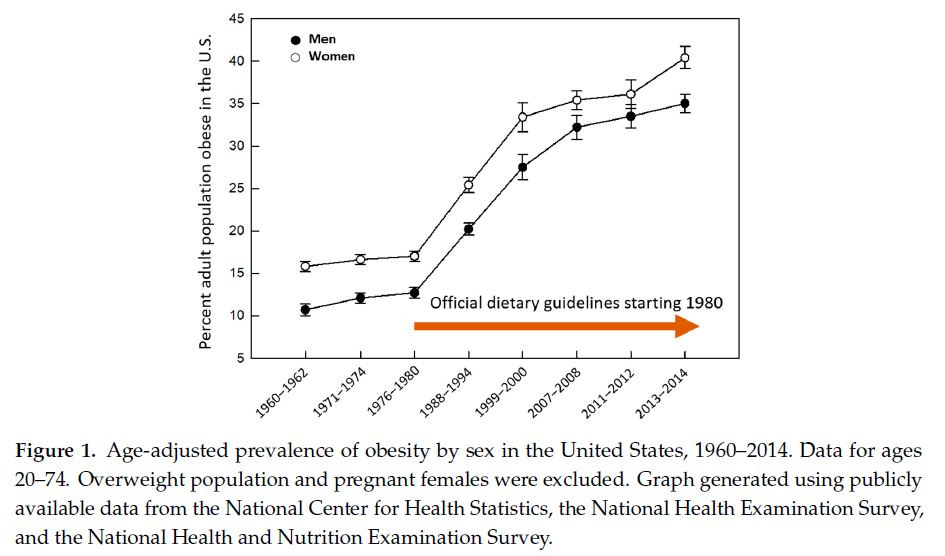

Here is another chart illustrating the correlation between the introduction of dietary guidelines and the rise in obesity in the US.

It is true that in these wealthy countries, so-called ‘obesogenic’ food abounds, so temptation and even addiction lurk in every mall, every drive-thru.

In the UK, food companies spend 30 times more on advertising processed food than governments spend on healthy diet promotion.

But what about countries with developing economies?

It’s well established that as developing countries adopt a ‘Western lifestyle’ including the diet, they develop the diseases of these wealthier countries—obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, autoimmune diseases, Alzheimer's disease, and many more. These diseases are rare or virtually absent in hunter-gatherers and other non-Westernised populations.

Is the increasing availability of junk food worldwide solely to blame?

Historical Perspective

For the vast majority of the time humans have been humans, we managed without published dietary guidelines.

No doubt there was general knowledge about the good and the bad in the available food, but generally, we ate what we found, and we thrived.

We were innovative and adaptable. We ate a variety of plants and animals, made tools, and used fire to cook food, making nutrients more readily available.

It's hard to determine exactly what we ate back then, but what we do know is that the foods recommended in the dietary guidelines we just discussed were not available.

Some of the ancestors of modern fruits and vegetables, fibrous and probably not very sweet, without decades of plant breeding, might have been available seasonally. Grains (grass seeds) might have been harvested laboriously by hand, again at certain times of the year.

The food that would have been available throughout the seasons would have been animals. With the additional difficulty presented by the need to catch and kill, large herbivores to small rodents, insects, reptiles, fish, and crustaceans would have all been on the menu.

This is how we ate for 290,000 of the 300,000 years we've been humans.

Very little ‘whole grains’, surgery fruits or vegetables, and plenty of animal protein and fat.

We remain innovative and adaptable. So, even with this dramatic shift in our diets in the last 3 or 4% of our history, we are still here. There are now 8 billion of us, and we collectively dominate and co-opt the Earth's resources.

But our health is declining. There are clearly other factors, but our diet is likely a major one.

A big rethink

Perhaps we need to fundamentally rethink our approach to dietary recommendations.

Rather than pursuing universal guidelines, we might better serve human health by understanding diet as part of a complex adaptive system, one that encompasses our evolutionary heritage, individual metabolic variations, and modern environmental contexts.

The evidence suggests that rigid dietary prescriptions, however well-intentioned, often fail to account for the sophisticated interplay between human physiology and nutrition. A more nuanced, evidence-based approach that acknowledges both our biological heritage and individual variation might better serve our journey toward optimal health.

What would a mindful sceptic do?

A mindful sceptic would begin by acknowledging the profound complexity of human nutrition while remaining grounded in empirical evidence.

Rather than pursuing universal prescriptions, we might structure guidelines around fundamental principles that reflect both our evolutionary heritage and modern scientific understanding.

Key Considerations for a big rethink might be…

Evolutionary Context

Examine the metabolic flexibility that allowed humans to thrive across diverse environments

Consider the timeframes of human adaptation to different food sources

Understand seasonal and geographical variations in historical diets

Individual Variation

Account for genetic diversity in metabolic responses

Recognise age-related nutritional needs

Consider microbiome variations and their dietary implications

Acknowledge cultural and environmental contexts

Evidence Quality

Prioritise long-term observational studies of diverse populations

Evaluate intervention studies for practical applicability

Consider the limitations of nutritional research methodologies

Examine funding sources and potential biases

Systems Integration

Map relationships between diet, environment, and health outcomes

Consider food production sustainability

Evaluate economic accessibility and cultural acceptability

Understand social determinants of dietary choices

The path to more effective dietary guidelines requires a fundamental shift from prescriptive rules about macronutrients and rigid food group servings.

Instead, we might reimagine guidelines as dynamic frameworks that acknowledge the sophisticated interplay between individual biology and nutrition. This approach would prioritise understanding how different bodies respond to various foods, recognising that metabolic flexibility—our remarkable ability to adapt to other fuel sources—has been key to human survival across diverse environments and epochs.

Consider how our ancestors naturally adapted their eating patterns to seasonal availability and local conditions. They intuitively understood their bodies' responses to different foods through necessity and experience.

Modern guidelines could draw inspiration from this adaptive capacity, offering tools and frameworks that help people explore and understand their own metabolic responses rather than prescribing universal solutions. This might involve teaching principles of self-experimentation and careful observation, enabling individuals to develop personalised nutrition approaches that respect their biology and circumstances.

Quality and processing methods emerge as crucial considerations in this framework, moving beyond simply categorising foods as "good" or "bad."

Understanding how food processing affects nutrient availability and metabolic response provides more profound insights than counting servings or calculating macronutrient ratios. This nuanced approach acknowledges that the same food might affect different individuals differently, depending on their genetic makeup, gut microbiome, activity level, and numerous other factors.

The Mindful Sceptic's Framework for Dietary Research might look something like this…

Question Assumptions

"Is this recommendation based on robust evidence or historical accident?"Examine Context

"Under what conditions does this dietary pattern promote health?"Consider Complexity

"How do various factors interact to influence nutritional outcomes?"Evaluate Evidence

"What is the quality and relevance of supporting research?"Acknowledge Uncertainty

"Where are the gaps in our understanding?"

The path to more effective dietary guidelines requires striking a balance between scientific rigour and practical applicability.

A mindful sceptic's approach would prioritise:

Evidence-based flexibility over rigid prescriptions

Individual adaptation over universal rules

Systems thinking over reductionist models

Critical evaluation over authoritative acceptance

This framework challenges us to move beyond simplistic nutritional narratives while maintaining scientific credibility and practical utility.

It suggests that the most effective dietary guidelines might teach people how to think about food rather than simply telling them what to eat.

Mindful Momentum

Transform your relationship with food by adopting an investigator's mindset.

Rather than accepting or rejecting dietary advice wholesale, maintain a research journal to document your body's responses to various foods and eating patterns. Notice how energy levels, mood, and digestion fluctuate under multiple conditions.

This systematic self-observation, combined with understanding broader nutritional evidence, creates a robust framework for personal discovery.

Consider tracking not just what you eat, but environmental contexts, stress levels, sleep quality, and physical activity. These observations often reveal patterns that generic guidelines miss.

Remember…

You're not testing yourself against an arbitrary standard but gathering data to understand your unique metabolic responses.

Key points

Modern dietary guidelines present a paradox: despite unprecedented access to nutritional information and advice, wealthy nations face escalating rates of obesity and diet-related diseases. This disconnect raises fundamental questions about our approach to nutrition and highlights the need for more nuanced, evidence-based analysis of dietary recommendations.

Historical perspective reveals that humans thrived for 290,000 of our 300,000-year existence without formal dietary guidelines, adapting to diverse food environments through metabolic flexibility. This evolutionary context suggests our current prescriptive approach to nutrition may overlook crucial aspects of human dietary adaptation and individual variation.

Evidence suggests that adopting Western dietary patterns is associated with higher rates of metabolic diseases, even in developing nations. However, this relationship extends beyond simple food availability, suggesting deeper systemic issues with current nutritional frameworks and their underlying assumptions about human dietary needs.

A mindful sceptic's approach to nutrition emphasises understanding individual metabolic responses, questioning established guidelines, and recognising the complex interplay between biology, environment, and diet. This framework suggests that effective dietary guidance should teach critical thinking about food, rather than prescribing universal rules, and acknowledge both evolutionary heritage and modern scientific insights.

You Might Also Like

Curiosity Corner

This issue of the newsletter is all about…

The paradoxical rise in diet-related diseases despite increased nutritional knowledge suggests we need to fundamentally rethink dietary guidelines through a systems-based lens that acknowledges both our evolutionary heritage and individual metabolic variation.

Better questions on this topic might include…

How did human metabolic flexibility evolve before modern food processing, and what does this reveal about our current dietary guidelines?

What systemic factors beyond individual food choices drive the paradoxical increase in metabolic diseases across cultures adopting Western dietary patterns?

If current dietary guidelines are based on scientific research, why do populations following them experience declining health outcomes?

How might understanding individual metabolic variation transform our approach to nutritional advice?

What can we learn from the 290,000 years of human dietary adaptation that preceded formal nutritional guidelines?

In the next issue

The Two Kinds of Knowledge We Can't Reconcile

What do a voting booth and a grocery store have in common? They both reveal a peculiar gap in how we perceive our world.

Join us next week as we unravel the curious disconnect between what we think matters (hello, election promises!) and what keeps our civilisation running.

We'll explain why this matters more than ever for both your personal choices and our shared future.

Useful evidence

Dey, Moul, and Purna C. Kashyap. “A Diet for Healthy Weight: Why Reaching a Consensus Seems Difficult.” Nutrients 12, no. 10 (September 30, 2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12102997.

Herforth, A., Arimond, M., Álvarez-Sánchez, C., Coates, J., Christianson, K., & Muehlhoff, E. (2019). A Global Review of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Advances in Nutrition, 10(4), 590–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy130

Kopp, W. (2019). How Western Diet And Lifestyle Drive The Pandemic Of Obesity And Civilization Diseases. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 12, 2221–2236. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S216791

Hint: humans were taller and had bigger brains and fewer dental caries during the pre-agrarian (hunter-gatherer) period.

Great info! Thanks!