TL;DR

Western liberal democracy governs just 13% of humanity, yet we’ve built our entire worldview assuming this minority experience defines universal political aspiration. Democracy emerged during the era of fossil fuel abundance and promised perpetual growth for a billion privileged people. Extending this model globally would require 400% more resources, even though we’ve already breached six planetary boundaries. The mathematics are brutal. Meanwhile, 7 billion people navigate life under alternative governance systems that evolved strategies for resource scarcity rather than abundance fantasies. These systems feature stronger state coordination, fewer consumption promises, and cultural adaptation to limits. The uncomfortable reality is that our democratic institutions become brittle when defending their form against resource constraints, thereby consuming energy that would otherwise be used for practical adaptation. Because the polycrisis operates according to physical laws, not political preferences, we need governance that enables legitimate decision-making, adaptive capacity, distributed experimentation, and fair resource allocation, all within ecological limits. But the governance systems we cherish most may not be the ones humanity needs when abundance ends.

After Donald Trump won his second term, I stopped listening to political podcasts. I had been an avid consumer, soaking up all the analysis and gossip from the pundits as though they were genuine gurus; the real deal.

The Rest is Politics was one of my favourites, and for months, the 2024 UK election held sway with its prospects for a landslide into power for the left in a country that has always thought it was right. No matter that it had been run for years by pathological liars and the ultra-privileged, with all traces of empathy gone.

Will they do it? Surely they must. Can it be? Yes.

I felt the anticipation and the relief all the way from the Antipodes.

When the podcasts had milked all the tension, they swiftly transitioned. Soon they were asking, ‘How would the Democrats go? ’ in the US. And when the US results came in, my gurus were stunned, near speechless, and wrong. They had assumed that the process of democracy was proper and would deliver a sensible result. When it didn’t, they were speechless and couldn’t admit why their hubris failed them, and I ghosted them all in dismay.

But my cold turkey on the commentary didn’t negate the political turmoil or my emotional exposure. I had to do something. So I thought about it, had a few conversations with the chatbots and came to a realisation… I, they, we, don’t know the half of it.

Because we are not even half of it.

The billion or so people in mature economies, which we refer to as Western or the Global North, have a consolidated worldview of capitalism dressed in a dark grey suit of democracy. I have been indoctrinated into this framework, using it to view the entire world order. This is both naive and stupid. There are 7 billion other humans who don’t have this specific experience of neo-liberalism and its entitled leadership. What do they think?

But before I could explore the social contracts employed by the vast majority of humanity, I had to start with the fear that my worldview—the trick that is liberal democracy—was in trouble.

Because I write about them all the time, I know the threats. They cascade across ecological, financial, and social systems, with each crisis making subsequent crises harder to solve. The polycrisis represents a new emergent condition of global vulnerability that requires understanding systems as a whole rather than addressing each crisis in isolation. It is the collective consequence of material progress and energy risk.

I can summarise it for you like this…

The global population of 8 billion people, increasing by 8,000 every hour, relies on a daily supply of 23 trillion kilocalories of food energy, generated through a fragile mix of subsistence farming and fossil fuel–driven industrial agriculture that, while sufficient in volume, is undermined by inefficiencies in distribution, waste, and nutritional quality. And it all has to follow the second law of thermodynamics.

We have ourselves a people problem.

https://open.substack.com/pub/mindfulsceptics/p/the-polycrisis-problem?r=4o0vy1&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

Writing about food security, population, biodiversity loss, and the myriad consequences of polycrisis in the Mindful Sceptic newsletter and various books is scary, borders on illegal, and readily brings on anxiety and depression. But it helps me to see the patterns. One is that more and more people are living in and seeking to join a system that exploits nature for human benefit because it offers comfort, safety, and luxury.

At the same time, many people in the Global North feel that the fruits are under threat or becoming increasingly scarce and hard to obtain. They somehow sense that the neoliberal economic system that has underwritten them for decades is being disrupted by the prospect of slower growth and the reality that Earth’s resources are finite.

One way out of such fear is to attach yourself to anyone brave enough to question the status quo, especially if they can identify with your tribe and promise a return to the good old days of plenty. This has, among other things, brought various right-wing political ideologies to power or to the brink of power.

So here is my first premise…

The disruption of Western democracy and its underpinning neoliberal economic model, driven by slowing growth and finite resources, has contributed to the rise of right-wing political movements.

For much of the post-World War II period, Western democracies operated within a broadly neoliberal economic framework built upon free markets, deregulation, and global trade. When all those factories that used to churn out munitions and warplanes were retrofitted for cars, tractors and whitegoods, it, for a time, delivered sustained growth and rising living standards.

When I was a kid in the UK, a colour television was a requirement for living above the poverty line. Now, everyone who wants one has at least two. They can go to a supermarket with 30,000 different food products and be told these wonders are theirs for a little hard work.

However, growth rates have slowed, inequalities widened, and the ecological limits of Earth’s resources have become undeniable. The neoliberal growth model’s assumptions are exposed. Its promises have become increasingly hollow. Voters disillusioned by stagnant wages, diminished opportunities, and environmental degradation question the legitimacy of political and economic elites who champion the old order.

If your wages have been declining in real terms, your landlord raises the rent, and all your utilities cost more, maintaining your living standard is becoming harder every day. A spike in egg prices, however temporary, becomes more than trivial. It signals a bleak future and a present marked by struggle.

In this uncertainty, right-wing political movements have found fertile ground. They offer simple, often nationalist, narratives that blame “outsiders”, especially immigrants, supranational institutions, or global corporations, for declining national prosperity and autonomy. They promise to restore control to the people, albeit through exclusionary or authoritarian means, positioning themselves as defenders against the failures of neoliberal globalism and liberal democratic institutions. In some countries, such groups have already attained power; in others, they are major opposition forces shaping national discourse.

In 2016, Donald Trump’s America First platform explicitly rejected free trade agreements like NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, criticised globalisation for harming American workers, and promised to restore manufacturing jobs. His appeal to economic nationalism and anti-immigration sentiment resonated, especially with voters who felt abandoned by both traditional conservative and liberal elites. In 2024, he came around again with more of the same, then carried out and carried on.

In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party consolidated power through an illiberal democracy that prioritised national identity and border control, and rejected supranational governance, particularly that of the European Union. Orbán’s government frames its policies as a defence against economic globalisation and demographic change, often blaming external forces for Hungary’s social and financial challenges.

Similarly, Italy’s right-wing parties, such as Lega and Brothers of Italy, have gained significant support by opposing EU fiscal rules, promoting strict immigration controls, and appealing to voters disillusioned with low wages and bureaucratic governance from Brussels.

All this is populism, less a fixed ideology than a political style or logic that sets up a binary conflict between the pure people and the corrupt elite. In these examples, it is right-wing populism, grounded in nationalism, cultural identity, and opposition to immigration or global institutions. It works through the rhetorical appeal to the will of the ordinary people, who are portrayed as morally superior to those in power.

While many find solace in the rhetoric, others are nervous. Some people see all this as new, disruptive and a threat to the liberal democracy that they were born into. But students of history can be more sanguine. None of this is new. It has happened before, to varying degrees. For example, in Europe between the wars and during the 1970s oil crisis. Even the Romans had populist leaders.

History prompts a second premise…

Historically, periods of economic disruption, perceived resource scarcity, and declining trust in political elites can fuel the rise of nationalist and authoritarian movements, reshaping or destabilising existing democratic systems.

Between the two World Wars, particularly during the 1920s and 1930s, many European nations experienced profound economic hardship, exacerbated by the Great Depression. One minute, you are partying hard through the Roaring ‘20s, and the next, 15 million Americans are unemployed—a quarter of the labour force. Traditional liberal economic models failed to restore prosperity, and democratic governments appeared incapable of solving massive unemployment, inflation, and social unrest.

In this environment of instability and fear, authoritarian nationalist movements, such as Mussolini’s Fascists in Italy and Hitler’s Nazis in Germany, rose to power. They offered simple, emotionally charged narratives that promised economic revival, national restoration, and the identification of scapegoats (minorities, immigrants, foreign powers) for the nation’s problems. There was endless hardship and tragedy before they were replaced.

In the late Roman Republic, as Rome’s expansion slowed and the costs of maintaining its vast empire increased, wealth became concentrated among a small elite. At the same time, ordinary citizens faced declining economic security. Political institutions that had once managed competing interests became gridlocked and corrupt, creating space for populist leaders like Julius Caesar to mobilise discontent against the traditional ruling classes. The Republic ultimately gave way to imperial autocracy, a transition primarily driven by the erosion of economic and social stability.

A more recent, yet instructive, case is the 1970s energy crisis. When oil prices quadrupled and economic growth slowed sharply, faith in post-war liberal economic management eroded, setting the stage for the rise of new political ideologies, including neoliberalism itself, championed by Reagan and Thatcher. While short of authoritarianism—although coal miners in the UK might disagree—neo-liberalism was a political shift to the right in an economic sense towards free markets and deregulation. The current shift extends further to the right, rejecting free-market orthodoxy, favouring economic nationalism and social conservatism.

So, something like modern populism has happened before. But surely this one is different. Today, there are more people with more crises in a highly interconnected world with an addiction to fossil fuels.

‘But today is different’ prompts a third premise…

While today’s political disruptions echo past crises, global interdependence, environmental constraints, and widespread digital communication make the current situation more complex and less predictable than historical precedents.

Today’s world is deeply interconnected economically, technologically, and environmentally. In the 1930s, it was much simpler. Back then, nations could retreat behind tariffs and nationalism without immediate global repercussions. They were somewhat self-sufficient, and their people had lower expectations of what would be available.

Today, supply chains, financial systems, and even basic resource distribution are tightly interlinked. For example, in 2023, the UK imported half of the food it needed to feed its population, at a cost of approximately £61 billion (US$76 billion) for food, feed, and drink. The trade gap between exports and imports was £37 billion (US$46 billion).

This is big money, equivalent to the GDP of Bulgaria ($77.8 billion), Myanmar ($76.2 billion), Ghana ($74.3 billion), or Oman ($74.1 billion). Attempts to radically decouple from globalisation, while politically appealing to some, risk causing immediate and severe domestic and international disruption. Unless you can be sure where the food is coming from, pause before you mess with your suppliers. It can get ugly fast.

The environmental context is also radically different.

Previous political crises were primarily human-driven and reversible through policy changes or economic recovery. Today, humanity faces irreversible ecological thresholds related to climate change, biodiversity loss, freshwater scarcity, and the transition from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources. Ecological limits impose rigid boundaries on economic and political choices. Leaders cannot promise unlimited growth or the exploitation of resources without worsening systemic risks. No amount of political rhetoric, however hard they lie, can ultimately dismiss this limit to growth.

The digital information environment changed the game. Mass media once moved slowly and sat in the centre. Now social platforms fracture discourse, speed polarisation, and give fringe ideas reach. Grassroots groups gain power, but extremists do too. Gatekeepers no longer mediate because they are also after clicks. Outcomes swing fast on emotion and, as a result, political outcomes have become increasingly difficult to predict. Not least because they can shift rapidly in response to emotionally charged narratives that often lack factual grounding.

This is just the helicopter view.

As you get closer to the ground, more nuance emerges. Here are a few for added flavour…

Automation, AI, and other technological changes are fundamentally restructuring labour markets and contributing to economic anxiety. This technological transformation is happening alongside resource constraints and may be equally important in driving political realignment.

While economic factors are important, many right-wing movements gain significant support from cultural anxieties about changing demographics, immigration, and perceived threats to traditional values and national identity. These cultural motivations often operate independently from economic concerns.

The effects of globalisation and neoliberalism have been unevenly distributed not only between social classes but also within regions of countries. This regional inequality (urban/rural divides, deindustrialised areas vs. tech hubs) often maps closely to political divides.

Populism is portrayed as primarily grassroots. Still, many right-wing movements have been actively cultivated by segments of existing elites for strategic purposes, from wealth creation to control.

Right-wing nationalism may be the primary response to neoliberalism’s challenges, but there are multiple competing visions emerging from progressive internationalism, green new deal proposals, digital libertarianism, renewed social democracy, to various forms of localism. The competition between these alternatives is a crucial dynamic shaping our political future.

And then there is the elephant of inequality pooping all over the carpet.

According to the UBS Global Wealth Report, as of 2023, the top 1% of the global population, encompassing individuals with a net worth exceeding $1 million, collectively own about 47.5% of the world’s total wealth, amounting to approximately $214 trillion. While the ultra-wealthy accumulate vast resources, a significant portion of the global population struggles with minimal wealth. For instance, adults with less than $10,000 in assets constitute nearly 40% of the world’s population (over 3 billion people), but hold less than 1% of global wealth.

From here I could, and have, disappeared down into the rabbit warren to try and comprehend the patterns, learn and predict the future. All the while, assuming that the helicopter was hovering over a liberal democracy somewhere in the Northern Hemisphere.

I have a myopic view of the world.

And because I have such a narrow view, the next premise becomes…

The paradigm of disruption that describes the political and economic reality for the billion or so people living in mature economies that identify as liberal democracies must be the dominant paradigm that defines the other 7 billion souls, especially given that they face similar global resource constraints.

Does this premise hold?

No, not even close. I find it hard to believe that liberal democracy is the only one everyone knows, just because it’s what I’ve come to understand and internalise through decades of experience. Far from it.

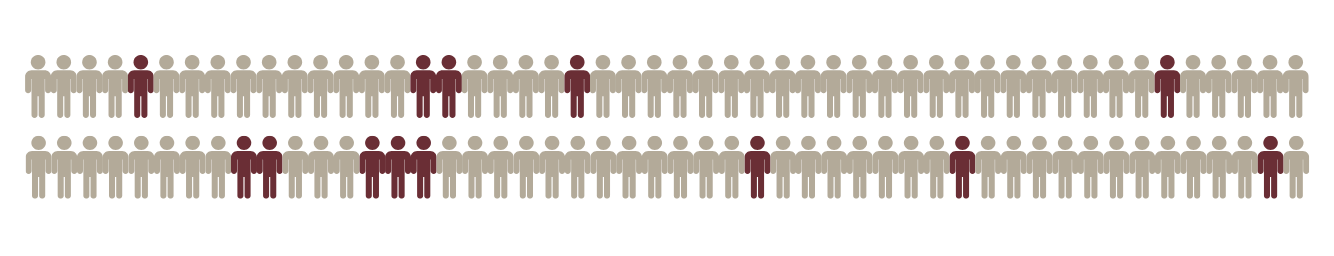

As of 2023, approximately 13% of the global population lives under liberal democracies, according to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute. This is around 1 billion. So the vast majority of people in the world, the other 7 billion people, are governed by design or choice, under an alternative to Western liberal democracy and neoliberalism.

It would take a while to cover the alternatives, but here is a shortlist of the obvious ones…

State-led developmental capitalism, most prominently represented by China, but also visible in Vietnam, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and others. This model features a strong central authority directing economic development, prioritising stability and growth over individual liberties, and engaging strategically in markets while maintaining state control of key sectors. It’s often described as “authoritarian capitalism” and has gained legitimacy through delivering material improvements and national pride.

Religious-cultural governance models are seen in various forms across the Middle East, parts of South Asia, and elsewhere, where religious values shape political institutions and economic priorities. These systems usually reject Western secularism while selectively adopting economic liberalisation.

Neo-patrimonial and clientelist systems are common across parts of Africa, Central Asia, and Latin America, where formal democratic institutions exist alongside informal power networks based on patron-client relationships. A significant proportion of economic resources is distributed through personal connections rather than market mechanisms or formal state structures.

Post-colonial resource economies exist where nations remain primarily defined by resource extraction, with wealth concentrated among elites connected to global markets. International corporations, foreign governments, and multilateral institutions heavily influence the economic and political systems of their countries.

Subsistence and informal economies are the social governance system for billions in rural areas and urban slums. Neither the state nor formal market institutions significantly shape daily life. Instead, local community arrangements, traditional practices, and informal economies predominate.

Unlike Western democracies, which are experiencing disruption after decades of relative stability, many of these alternative systems emerged from colonial legacies and have long been adapting to resource constraints, international pressures, and internal challenges. They are a response to regular disturbance, risk, and uncertainty, and have evolved a complex tapestry of adaptation strategies developed with, rather than despite, resource limitations.

For example, many non-Western nations are pursuing aggressive resource nationalism, tightening state control over critical assets while simultaneously engaging strategically with global powers to leverage geopolitical advantages. Regional economic integration has gained momentum as countries seek collective resilience against external shocks.

Population approaches vary dramatically across these nations. Some implement pro-natalist policies to maintain demographic strength, while others pursue aggressive family planning to reduce resource pressures.

Perhaps most pragmatically, many selectively adopt green technologies, not necessarily out of environmental conviction, but because such innovations offer competitive advantages or resource security in an increasingly constrained world.

So, not only is the ‘liberal democracies must be the dominant paradigm’ false because the numbers don’t stack up, but also because resource constraints and environmental challenges ultimately reinforce rather than undermine many of the alternative governance models. Most of them already incorporate a stronger state direction of resources and make fewer promises about unlimited individual consumption than Western liberal models.

The point here is that my experience of democratic primacy might feel good, and indeed may even be good if it were true, but it is not.

Here is another way to see it…

Take 100 people at random from the global pool, and just 13 of them will be living under a Western-style democracy. Numerically, at least, people like me are in the minority. I’ll come back to this crucial point.

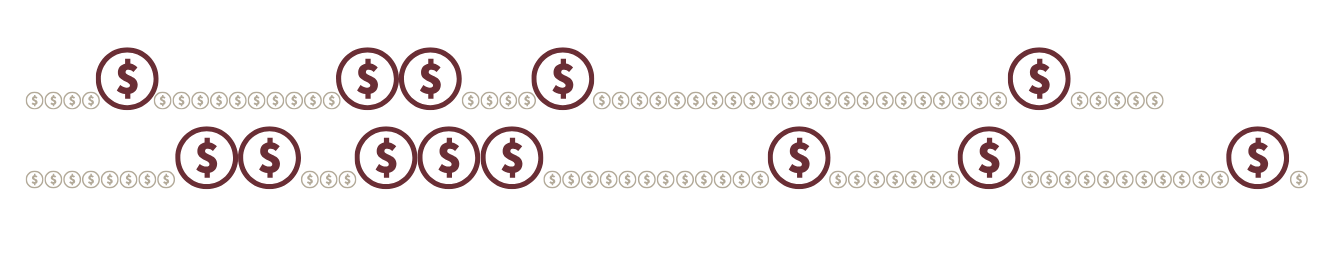

Of course, if I selected based on economic grunt, a very different proportion appears. According to the Global Wealth Report 2023 by Credit Suisse, North America and Europe together account for a substantial share of global wealth, with North America alone accounting for approximately 29.4%. When combined with the wealth held in Western Europe and Oceania, the total share held by Western democracies rises to an estimated 60% to 70% of the total.

If I simplify the issue and assume there are 100 units of wealth globally, then those 13 folk hold 65 of them, roughly 5 each. The other 87 share the remaining wealth, 0.4 units each.

This is the well-established north-south divide, which is in no small part why I prefer it if the helicopter flies only over my patch. From this view, I see the majority of folk with the 5 units and can ignore the majority with their 0.4 units.

But what if I see the proportions and realise that numbers and the impact are very different?

Perhaps I succumb to the guilt of my good fortune and decide that denying the majority a fairer share is unjust. But rather than give up my share, which is hard to do, I decide that the Western paradigm should prevail and spread out to the other 7 billion to see everyone at 5 units of wealth.

This approach is morally sound, makes me feel good, and still leaves me in possession of my SUV, but it requires an initial 100 units of wealth to increase by 400 units.

How awesome is this? If Western democracy and its underpinning neoliberal economic model spread to everyone on Earth, how much money could be made?

Sound familiar?

Except that every dollar is attached by the umbilical to a unit of energy and, by extension, physical resources. Energy use and resource use have to quadruple to increase the 100 to 400 units. But you already know the problem and what comes next.

The concept of planetary boundaries, developed by a team of Earth system and environmental scientists led by Johan Rockström and Will Steffen, defines limits within which humanity can safely operate to avoid destabilising the Earth system. The nine boundaries include climate change, biosphere integrity, land-system change, freshwater use, biogeochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus), ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol loading, stratospheric ozone depletion, and novel entities (e.g. chemical pollution). Each boundary represents a threshold or tipping point beyond which abrupt and potentially irreversible environmental changes could occur.

According to the most recent data from 2023, six boundaries have been transgressed:

Climate change results from greenhouse gas emissions exceeding safe levels.

Biosphere integrity is marked by accelerating species extinction and loss of ecosystem functions.

Biogeochemical flows are primarily from the overuse of nitrogen and phosphorus in agriculture.

Land-system change resulting from large-scale deforestation and agricultural land conversion.

Freshwater change through over-extraction and disruption of natural water flows.

Novel entities such as plastic pollution and synthetic chemicals, including PFAS, are pervasive and often persistent in the environment.

These breaches interact and amplify one another, creating compounded risks. For example, biodiversity loss undermines the resilience of ecosystems needed to adapt to climate change, while pollution exacerbates freshwater stress and harms aquatic life. The planetary boundaries framework warns that continued pressure in these domains risks tipping Earth into a less hospitable and more unstable state.

If current human activity strains the planet’s capacity for available energy, resource use and waste to produce the equivalent of 100 units of wealth, raising that amount by 400 is impossible without collapse.

Feeling a little nauseous, I ask the pilot to land the helicopter.

Once back on the ground with soil under my toes, I came up with a new heretical premise.

Alternative paradigms and ideologies to liberal democracy are better positioned to address a global resource crisis.

Does this premise hold?

“Wo’ah, hold on there, buddy,” said the pilot, taking off his sunnies to better stare into my face. “We can’t have any commies here.”

I smile and ignore my inclination to grasp the yolk of capitalism for dear life because certain aspects of non-Western paradigms may indeed be better positioned to navigate resource constraints. Non-Western governance models often feature centralised decision-making capacity that enables rapid, coordinated responses. They avoid the political gridlock common in liberal democracies, allowing long-term planning and swift crisis management when needed.

Many societies outside the Western sphere haven’t constructed their social contracts around promises of perpetually increasing material consumption; their citizens often have cultural practices that emphasise collective adaptation and greater familiarity with resource limitations.

In regions where formal institutions have historically been limited, informal community networks have developed remarkable skills at distributing scarce resources and adapting to changing conditions. These social technologies represent significant adaptive capacity that formal systems often lack.

Additionally, many developing nations are building infrastructure now rather than decades ago, allowing them to incorporate resource-efficient designs from the outset rather than face the costly challenge of retrofitting aging systems built during an era when resource abundance seemed limitless. This timing advantage may become increasingly significant as global resource constraints tighten.

Alright, so I might not like the idea of authoritarian control, but I have to admit that versions of the social contract exist that do not have growth baked into them.

But it is not all roses.

Population pressure remains a critical concern, with several regions experiencing ongoing demographic growth that intensifies competition for essential resources such as water, arable land, and energy. Authority and realistic social contracts might better manage shortages, but they can’t conjure food security, clean air and general well-being from thin air. Apparent advantages in centralised decision-making may not be enough if economic activity sufficient to meet the more modest social expectations becomes ecologically impossible.

The post-colonial economic structure presents another vulnerability, as many nations remain heavily dependent on exporting raw materials or agricultural commodities. They lack local value-add capabilities and are exposed to market volatility in raw materials and to resource depletion.

Aside from constraints on liberties, history suggests that authoritarian systems can be fragile. The balance between expectation and delivery is a fine one, no matter the governance system. ‘Better placed’ might not be the right question, as it sets up a comparison rather than an assessment of what will make an economic and governance system robust in a time of crisis or, as now, a polycrisis.

Instead, here are some features that the most resilient systems will likely possess…

Strong state capacity for coordination and planning

Distributed local adaptation capacity

Cultural flexibility to accept changing consumption patterns

Technical innovation capacity

Legitimate governance that can maintain social cohesion during difficult transitions

These combinations exist across different governance paradigms. Success in the face of resource constraints may depend more on specific implementation than on broad ideological categories. You can have these features in more than one flavour of government and economy.

When abundance ends, a liberal, money-making free-for-all is unlikely to persist for long, but neither would a draconian ruler or a fully social ideology. What works might not even exist just yet.

The helicopter pilot tuned out long ago and is passing the time flirting with the receptionist. I pull him away to take one last flight above liberal democracy for the last premise that I can’t shake…

Fear and anxiety over the risks to liberal democracy hinder the ability of the 1 billion in the West to cope with the polycrisis

Does this premise hold?

Yes, it does.

When political discourse fixates on threats to democracy, it compounds the short-term thinking inherent in election cycles. Planning becomes increasingly difficult. Politics turns even more to symptoms rather than underlying systemic challenges, and policy is forgotten in the heat of the political battles.

The us-and-them mentality pervades and transforms resource allocation, turning pragmatic problem-solving into zero-sum political warfare. As citizens divide into camps viewing the “other side” as an existential threat to democracy itself, collaborative action becomes nearly impossible. Even basic infrastructure decisions that could enhance resilience become battlegrounds for identity politics, preventing the unified response that resource constraints demand. Climate adaptation strategies are particularly affected by this problem.

Democratic institutions often become brittle.

Rather than experimenting with novel approaches, they become rigid and defensive, even at the cost of preserving existing structures. This institutional calcification reduces the capacity for learning and evolution precisely when flexibility becomes most crucial. The irony is that in defending democracy’s form, we risk sacrificing its essential adaptive function.

Then the people lose faith in the system just when resource constraints require difficult trade-off decisions. Inevitably, some consumption patterns must change, some industries must transform, and some comfortable habits must evolve. When citizens no longer trust democratic institutions to distribute these sacrifices fairly. People resist even necessary changes as illegitimate impositions, and soon we see vicious cycles of institutional failure.

Perhaps most insidiously, battles over democracy’s future consume social energy that might otherwise be devoted to practical adaptation to environmental challenges. These democracy-centred debates, while undeniably important, can function as sophisticated displacement activities. Chairs on the Titanic are moved, rearranged and moved back again, perhaps replaced with recycled plastic ones, and we feel like we engage with critical issues, while avoiding the more uncomfortable material realities of planetary boundaries.

But democratic systems also possess unique strengths that resilient systems possess…

The capacity for decentralised innovation and problem-solving

Robust feedback mechanisms that can identify failures quickly

The ability to build broad legitimacy for difficult transitions when done well

Transparency that supports accountability and learning

Of course, instead of contemplating alternatives to liberal democracy and its neoliberal economics, we could hold on to all the good bits and realign the wealth differently.

The 13 folk in the west among the 100 in the world could go from 5 units of wealth each to one unit, still a full 60% more than the current wealth of those not in a liberal democracy. If the 52 units of wealth this liberates are spread evenly, everyone gets 1 unit.

This sounds fanciful and is the exact opposite of what capitalism has delivered for the last 50 years, but we could. We could change the relationship between democracy and resource constraints, making them interconnected rather than in competition.

For this premise, protecting democracy is essential precisely because navigating reallocation on such a scale requires legitimate governance that can distribute sacrifices fairly and adapt quickly.

“Can we land now, buddy?” said the pilot, “I have a date.”

The helicopter touches down, and the pilot heads off, leaving me with uncomfortable realisations.

I’ve lived within a worldview representing just 13% of humanity, believing it to be universal. And I’ve worried about threats to liberal democracy without questioning whether its current form suits our resource constraints. But the truth is that the polycrisis we face doesn’t care about our political preferences. Climate disruption, resource depletion, and ecological breakdown operate by physical laws, not ideological ones.

Perhaps the most mindfully sceptical position isn’t defending liberal democracy against all alternatives, but asking the more fundamental question…

What governance features, regardless of their ideological packaging, best support human flourishing within planetary boundaries?

This isn’t about abandoning democratic values but expanding our field of vision. When we obsess over protecting our familiar systems against change, we burn precious adaptive capacity that could be directed toward the underlying resource challenges. Meanwhile, billions of people already navigate life under different governance arrangements, some of which may be better attuned to resource constraints.

Rather than viewing this through the binary lens of “liberal democracy versus everything else,” a mindfully sceptical approach suggests focusing on specific governance capabilities that foster resilience…

Legitimate decision-making processes that can distribute necessary sacrifices fairly and maintain social cohesion during transitions

Decentralised experimentation that allows communities to develop context-appropriate solutions

Long-term planning capacity that can transcend electoral cycles and market short-termism

Cultural narratives that define prosperity beyond material consumption

Transparent accountability mechanisms that prevent corruption and maintain public trust

These features can exist within various governance frameworks; some more democratic, some less so. In the coming decades, hybrid approaches will likely emerge as societies pragmatically adapt to ecological realities regardless of ideological purity.

For those raised in Western liberal democracies, this requires intellectual humility. We must acknowledge that our systems were developed during an anomalous period of resource abundance and may require profound evolution. Yet this needn’t mean abandoning core values like human dignity, transparency, and accountability.

The mindful sceptic’s approach isn’t to defend democracy’s current form at all costs or abandon its essential virtues, but to engage in the messy, creative work of evolving governance for a resource-constrained world.

This means learning from diverse systems globally while applying the best aspects of democratic feedback, legitimacy, and adaptation.

Perhaps what emerges won’t neatly fit into our current political categories, precisely as it should be. The challenges ahead demand something new.

Quick point. We've breached seven planetary boundaries, not six. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/news--events/general-news/2025-09-24-seven-of-nine-planetary-boundaries-now-breached.html

Even breaching one planetary boundaries means we've gone too far in abusing the planet. Now we've breached seven and few people seem to think there will be dire consequences as a result. Talk about denial.