The Calorie Paradox

Why feeding humanity better than ever before might be our biggest vulnerability

The average daily energy consumption is above the 2,500-kilocalorie threshold required to maintain human body weight in all world regions, which is a remarkable achievement.

I have always been on the tubby side of the ideal weight.

My BMI of 26.9 technically puts me in the "overweight" category according to general guidelines. I have always been a little disappointed in this because getting my endomorph body into the ‘healthy’ range has proven challenging.

Endomorphs tend to have a larger bone structure and a higher body fat percentage. They often carry more weight around the belly, hips, and thighs and may have a rounder body shape. That’s me.

So, I have to live with a slower metabolism, an efficient storage of nutrients as fat, and the ability to gain weight by just looking at a vanilla slice.

Imagine my excitement when I discovered that research indicates that a BMI between 25 and 27 might benefit older adults, offering protection against conditions like osteoporosis and better recovery from illness.

Bring it on.

But this issue of Mindful Sceptics is not about me. It’s about the remarkable reality that the energy consumed in food by the average global citizen has increased steadily in the last 60 years and is 35% higher than when I was born in 1961.

A global average, John and Jane Wang consume more energy than they need for maintenance. They are not starving because humanity grows enough food.

This is remarkable given that in those decades the human population has increased by approximately 5.17 billion people, an average annual rate of change of approximately 2.63%.

As you read, the global population increases by another 8,000 people every hour.

But thanks to the incredible efforts of a relative handful of farmers and a large energy subsidy from fossil fuels, on average, over 8 billion people receive 2,957 kcal of energy from food daily, for a total worldwide of 23.9 trillion kcal.

That represents a lot of food.

This issue of Mindful Sceptic is an expanded version of a chapter in our Mindful Sceptic Guide to Growing Enough Food because this week, I want to examine energy consumption and production more closely.

Is it enough, and can it last?

Getting enough energy

In 2023, the global average daily energy consumption for all humans was 2,957 kcal, or approximately 23.91 trillion kcal for everyone.

Single metrics hide many sins, but the average global citizen is above the threshold for energy intake, a good indicator of food consumption. For energy needs, at least, the average human is getting enough food.

And the trend in food consumption is rising.

That global average is 747 kcal, or 35% higher than when I was born in 1961.

Comparisons with historical food consumption are also revealing. Here is a curious quote I came across recently

‘the energy value of the typical diet in France at the start of the eighteenth century was as low as that of Rwanda in 1965, the most malnourished nation for that year in the tables of the World Bank’.

Fogel, R. W. (2004). The escape from hunger and premature death, 1700-2100: Europe, America, and the Third World (Vol. 38). Cambridge University Press.

This sounds like a remarkable statistic. Even as the population tripled, it took just 200 years to double the French citizens' energy consumption.

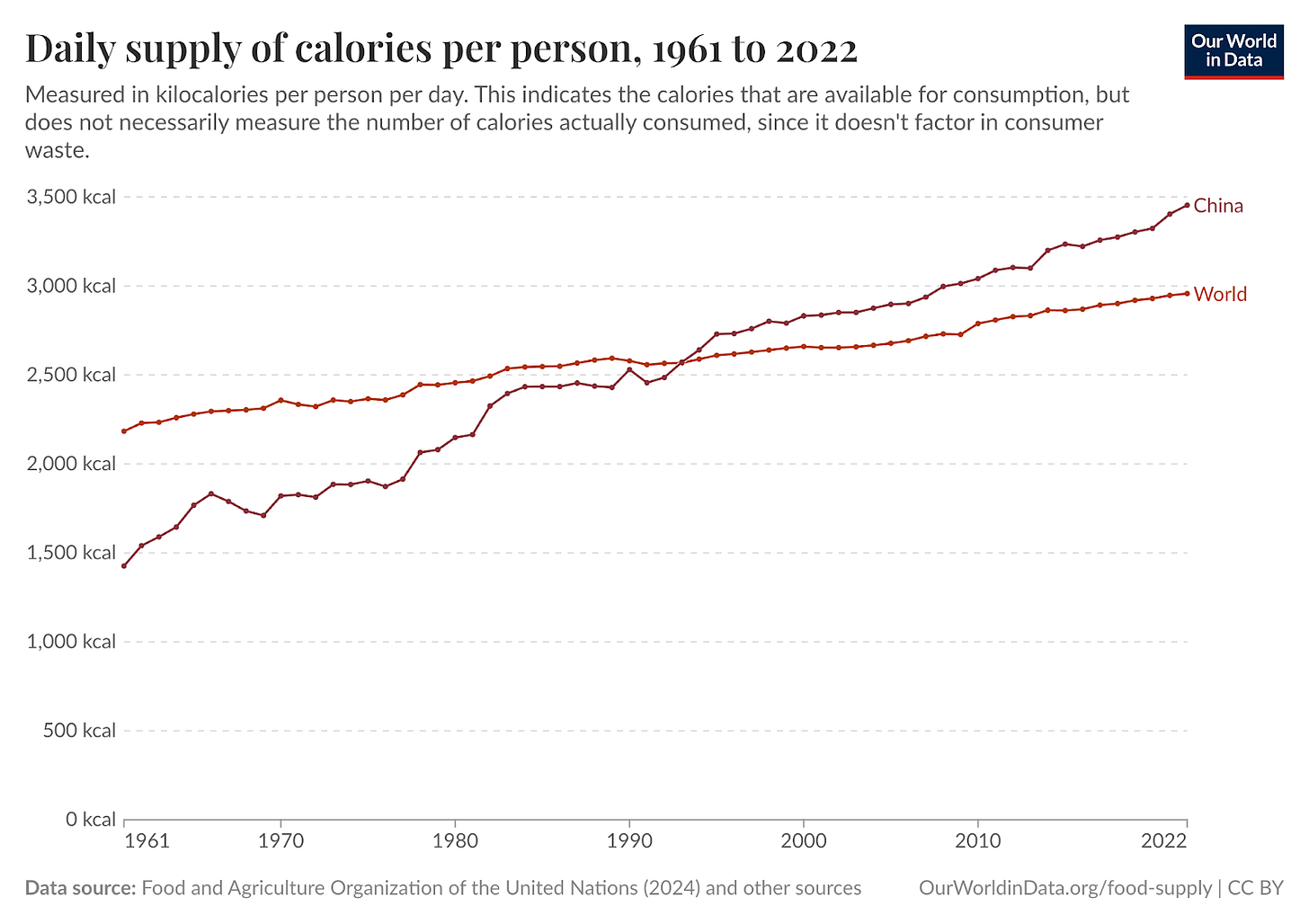

The same can be said for China.

In the 1960s, the daily per capita supply of calories was below 1,500 kcal. Today, China supplies over 3,100 kcal per capita, with a population of 1.39 billion (2018), again more than double the number in 1960.

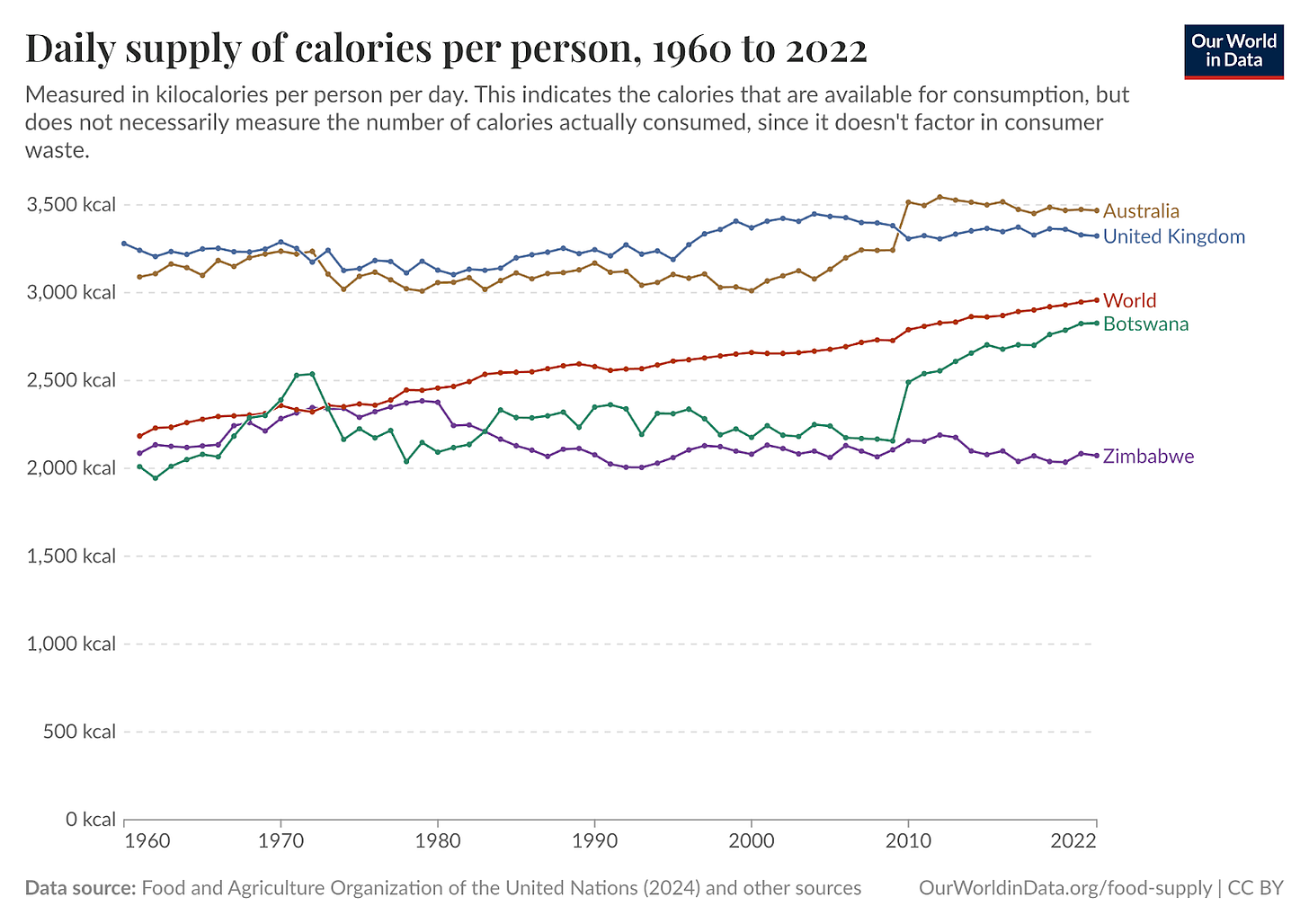

The point of these comparisons is that the availability of food measured as calories consumed per person per day generally increases over time, as this graph from the Our World in Data website shows for the world and the countries I have lived in over my 63 years.

There are regional differences, with some losses, particularly in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and some declines in North America in more recent times. And it is always wise to be cautious with averages, especially in the absence of any variance measure, but overall, food availability worldwide has improved.

This is a good thing and truly remarkable. No other organism has been able to do anything like it.

So what happens next? Does the trend continue to rise, stabilise or reverse? Do we even know what should or could happen?

The Fine Line Between Enough and Too Much

Humans are heterotrophs, organisms that obtain their energy and nutrients by consuming other organisms or organic matter. Unlike autotrophs (like plants), heterotrophs cannot produce their own food; we have to eat.

All things being equal, an average woman needs to eat about 2,000 kilocalories per day, and an average man needs 2,500 kilocalories to maintain body weight. Given that the global and regional averages are above 2,500 kilocalories, there is enough food to meet this energy need.

In the aggregate, the average daily energy consumption meets this requirement almost everywhere. Also, the kilocalorie trends are positive.

This means the global trend has been for increased food production and availability, at least in the aggregate.

The number of people who are short of food is indeed declining. The Chinese example, in particular, is a remarkable story of maintaining growth in food per capita that now stretches to protein consumption. For instance, pork has been a big part of Chinese cuisine as far back as 7,000 BC, and by the 1900s, at least 70% of animal calorie intake in China came from pork.

Today, consumers in China devour roughly 54 million tons annually, the highest total worldwide. This is no surprise given the size of the population, but per capita consumption has also grown steadily since the early 1980s.

When I was born in 1961, per capita pork consumption in China was roughly 5kg per year, whereas by 2023, it was over 40 kg per annum.

Daily energy from food in China was just shy of 1 trillion kcal in 1961, in 2023 it was just shy of 5 trillion kcal… per day.

However, an ever-higher average daily energy consumption can create problems.

For example, France went from famine and malnutrition 200 years ago to approximately 17% of French adults classified as obese in 2022, with nearly half the adult population (47.3%) falling into the combined overweight and obesity categories. The latest 2024 estimates push this figure even higher, with obesity now affecting 18.1% of the French adult population.

Our relationship with food security has fundamentally transformed. In mature economies, the public health priority has gone from ensuring adequate nutrition to managing overconsumption.

Current OECD estimates suggest that over half the global population will be living with overweight and obesity within the next decade, potentially by 2035, if current trends persist. This fundamental dietary pattern and lifestyle shift will affect over 4 billion people.

Many of us eat a caloric surplus because of several factors…

The proliferation of ultra-processed, energy-dense, and nutrient-poor foods that are readily available, often inexpensive, and heavily marketed products contributes significantly to excess calorie intake.

Sedentary lifestyles exacerbate the imbalance between calorie intake and expenditure.

Economic development and urbanisation combine to shift diets towards more processed foods and higher animal product consumption, while urban environments can limit opportunities for physical activity.

Many of us live in an "obesogenic environment" that includes food pricing, marketing strategies, urban planning that discourages walking or cycling, and socio-economic disparities that limit access to healthy food and active living options.

The consequences of this trend are far-reaching.

Beyond the immediate health impacts like increased risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, certain cancers, and musculoskeletal disorders, the economic burden is immense.

The OECD estimates that obesity and overweight-related diseases could reduce life expectancy by nearly 3 years and cost health systems a significant portion of their budgets, potentially reaching hundreds of billions of dollars annually. This also translates to reduced productivity and lower GDP due to increased absenteeism and presenteeism (reduced productivity at work).

There is too much of a good thing.

And then there are the people who are malnourished because they cannot get enough food, because not everyone is a John or a Jane.

Plenty of food but millions still hungry

According to the latest State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report, jointly produced by the FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO in 2023, around 2.33 billion people globally still experienced moderate or severe food insecurity.

This figure has remained stubbornly high since the sharp upturn observed in 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Within this group, over 864 million people experienced severe food insecurity in 2023, meaning they went without food for an entire day or more at times.

In 2022, over 3.1 billion people could not afford a healthy diet. Even for those with some access to food, the quality and nutritional adequacy of their diets are often severely compromised.

Here is the stark reality.

Despite adequate global food production, around 750 million people, approximately one in eleven people worldwide, faced hunger (undernourishment) in 2023.

There are many reasons for this.

Conflict and insecurity disrupting local food production, climate extremes, economic shocks, high food prices, and forced displacement are interconnected crises, making achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger) by 2030 increasingly challenging.

In other words, nearly a third of the global population is food insecure, and not all live in poorer countries.

As of Fiscal Year 2024, an average of 41.7 million Americans receive monthly benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps. To put this into perspective, Canada's current estimated population in 2025 is approximately 40.1 million people.

Hunger is one thing, adequate nutrition is another.

Over half of the global population is estimated to consume inadequate levels of at least one essential micronutrient.

But you get the point.

Then there is the elephant in the room.

Maintaining the average daily energy consumption

The challenge for the next 50 years is to let the average daily supply of calories plateau even as the net demand for food grows due to global population increases.

If we let energy intake increase, we end up with malnourished, overweight people.

Equally, we must address distribution and food access for those who do not get enough calories.

It is not smart to increase the average daily energy consumption from food without addressing the variability. If the average goes up and the variance is maintained, we end up with ever-larger numbers of people malnourished—some get too many calories and some too few.

Then we see the elephant.

Every calorie that kept me plump through six decades and every one of those 23.9 trillion kilocalories feeding humanity daily comes with an invisible fossil fuel shadow.

Think about it.

The wheat in your morning toast required diesel-powered tractors, natural gas-derived fertilisers, and petroleum-based pesticides. The truck that delivered it to your local shop burned more diesel. Even that "organic" banana travelled thousands of miles on fossil-fueled container ships.

We've created the most successful feeding system in human history that would make our hunter-gatherer ancestors weep with envy. But here's the catch that should make any mindful sceptic pause… we're eating oil.

Roughly half of humanity (4 billion people) depend entirely on intensive agriculture's fossil fuel-powered magic trick. Remove the energy subsidy, and there simply isn't enough arable land, human labour, or traditional fertilizer to maintain current yields using pre-industrial methods.

This isn't environmental hand-wringing; it's systems thinking.

When I started my career studying soil ecosystems, I believed technology would seamlessly solve our resource constraints.

This particular elephant isn't just in the room, it's supporting the entire building.

No more oil might sound good on the climate marches, but if oil is eliminated, there will be insufficient food.

Intensive agricultural systems rely on inputs designed around healthy, productive soils. However, intensive production depletes the nutrient and organic matter content, and they degrade. The yield gap is closed when machines and inputs replace traditional systems, but there is no guarantee that yield can be maintained.

Global food production is precarious as it relies on long supply chains, is overly complex and vulnerable to shortages of critical inputs.

In short, global food production could go down.

What a Mindful Sceptic Thinks

A mindful sceptic is wary of curves that continually go upwards.

This is not because of innate pessimism, but from understanding natural systems. Resilient systems cycle; they don't go on exponential benders without eventual corrections.

When I see humanity's calorie consumption climbing steadily for sixty years, my ecological training whispers the uncomfortable truth that the trend could quickly pivot into a plummet and fall off the cliff.

This isn't doom-saying; it's pattern recognition.

The UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, captures this systems perspective perfectly….

"We are hurtling toward disaster, eyes wide open, with far too many willing it on wishful thinking, unproven technologies, and silver bullet solutions. It's time to wake up, and step up."

UN Secretary-General, António Guterres

I agree, but here's where mindful scepticism diverges from mere alarm. We're keen to find innovations that acknowledge both the mathematics of our predicament and the ingenuity of human adaptation.

Maintaining average daily energy consumption at a reasonable level that reduces malnutrition in both directions while maintaining food production as the climate changes represents a huge challenge that demands systems thinking, not silver bullets. We need more resilient food production systems that can still produce and equitably deliver 22 trillion kilocalories daily.

Such a delicate balance requires what we might call pragmatic radicalism, fundamental changes in how food is grown, what we eat, and how social structures deliver nutrition to dinner plates.

These transformations will not be easy, but they are possible. Unlike finding another planet to inhabit, reshaping our food systems is within human capability.

Fortunately, every challenge contains an opportunity.

We must find people with the energy, imagination, and intellectual courage to link the two.

The Mindful Sceptic's Conclusion

The story of our daily 2,957 kilocalories reveals humanity at our most paradoxical… triumphantly successful yet perilously vulnerable.

We've achieved something no species has ever managed. We tapped exogenous energy to convert nature’s resources into a human breadbasket capable of feeding billions more people than the planet's natural systems could traditionally support. Yet this triumph rests on foundations we're simultaneously trying to abandon.

This tension embodies the mindful sceptic's sweet spot of holding complexity without surrendering to paralysis. We can simultaneously celebrate our achievement while acknowledging its fragility. We can appreciate fossil fuels' role in preventing mass starvation while working toward alternatives. We can honour farmers who feed the world while questioning industrial agriculture's sustainability.

The path forward requires neither denial nor despair, but disciplined curiosity about what's actually possible.

Every time you open your refrigerator, you're participating in humanity's greatest logistical achievement and its most vulnerable dependency. That awareness becomes your starting point for meaningful engagement.

Mindful Momentum

The Fossil Fuel Food Audit

Track one meal from farm to fork this week. Pick something you eat regularly—morning coffee, sandwich bread, evening rice.

Spend 20 minutes researching its journey…

Where was it grown?

How was it processed?

What machinery, fertilizers, and transport were involved?

Don't aim for perfect accuracy; aim for awareness. You'll quickly discover how diesel, natural gas, and petroleum thread through even the simplest foods.

This isn't about guilt, but you might feel a twinge. It's about understanding the invisible energy infrastructure that feeds us.

Key Points

Global food energy availability has reached unprecedented levels, with the average human consuming 2,957 kilocalories daily in 2023—35% more than in 1961 despite population growth from 3 billion to over 8 billion people. This remarkable achievement represents humanity's most successful resource appropriation in evolutionary history, with countries like China transforming from near-famine conditions (1,500 kcal per person in the 1960s) to over 3,100 kcal today. Historical comparisons reveal the magnitude of this shift: 18th century French diets contained as few calories as Rwanda in 1965, yet within 200 years, France doubled its citizens' energy consumption while tripling its population. This trajectory demonstrates an unprecedented biological and technological triumph in feeding our species.

Despite adequate global production totaling 23.9 trillion kilocalories daily, a stark paradox emerges between abundance and scarcity, creating two distinct forms of malnutrition. While regions above 3,000 kilocalories per person face rising obesity rates—with France seeing 47% of adults classified as overweight or obese—approximately 2.33 billion people globally experience moderate to severe food insecurity, and 750 million face hunger. This distribution problem manifests even in wealthy nations, with 41.7 million Americans requiring food assistance through government programs. The challenge extends beyond calories to micronutrient deficiency, affecting over half the global population despite apparently adequate food supplies.

Modern food security rests entirely on fossil fuel dependency, creating humanity's most successful yet vulnerable system. Intensive agriculture that feeds 4 billion people requires diesel-powered machinery, natural gas-derived fertilizers, and petroleum-based pesticides, essentially making the global population dependent on "eating oil." This energy subsidy enables remarkable productivity increases but creates systemic fragility. The complex supply chains, degraded soils, and input dependencies mean that removing fossil fuels would immediately threaten food production for half of humanity, as traditional agricultural methods lack sufficient arable land and labor to maintain current yields.

Maintaining food security while transitioning away from fossil fuel dependency requires fundamental systemic transformation rather than incremental improvements. The mathematical reality is that current consumption trends will create billions more malnourished people in both directions of obesity and hunger. Solutions demand coordinated changes in agricultural methods, dietary patterns, distribution systems, and social structures around food access. This challenge represents both humanity's greatest vulnerability and its most critical opportunity for innovation, requiring systems thinking that addresses the interconnected nature of energy, environment, and nutrition rather than treating them as separate problems.

Curiosity Corner

This issue of the newsletter is all about…

Humanity has achieved the remarkable feat of increasing global food energy consumption by 35% since 1961 while adding 5 billion people, yet this triumph masks a dangerous paradox where billions face malnutrition in both directions—obesity and hunger—while our entire food system depends on the fossil fuels we're trying to eliminate.

5 Better Questions from this issue of the newsletter…

What does "enough food" actually mean when one in eleven people face food insecurity despite producing 23.9 trillion kilocalories daily?

This question pushes beyond the simplistic "is there enough food?" to examine distribution systems, access barriers, and the gap between production and consumption—revealing that food security is fundamentally about equity, not just quantity.

How might our fossil fuel-dependent food system respond to energy price volatility or supply disruptions?

Rather than asking whether we can "go renewable," this explores the immediate vulnerability of feeding 4 billion people who depend on intensive agriculture, forcing us to consider transition pathways rather than absolute solutions.

Why do we measure food security success through rising calorie consumption when it simultaneously creates both obesity and hunger?

This challenges the assumption that more calories equals better outcomes, highlighting how single metrics can mask complex systemic problems and the need for distribution-focused rather than production-focused solutions.

What assumptions about agricultural productivity am I making based on my own food experiences?

This personalizes the inquiry beyond abstract global statistics, encouraging sceptical examination of how our individual relationship with abundant food might blind us to the fragility of the systems supporting us.

How do we distinguish between agricultural innovations that reduce fossil fuel dependency and those that simply shift it elsewhere in the system?

This moves beyond surface-level "green" solutions to examine whether proposed alternatives address root dependencies or merely relocate them, demanding systems-level evaluation rather than component-focused thinking.

In the next issue

The Personal Discovery

What does a quest for Australia's perfect fish and chips reveal about global food systems?

Next week, I will take you from coastal caravan parks to industrial fish farms, exploring how aquaculture now provides over half our seafood and copies troubling patterns from land-based agriculture.

We'll unpack when "sustainable seafood" claims hold water and when they're just marketing spin.