TL;DR

Sustainability sounds good, feels good, and mostly allows the human enterprise to continue on its merry way. It’s a floating signifier that is morally coated and operationally vague, used to defer hard choices and decorate business-as-usual. Behind the rhetoric lies a psychological balm for professionals and the public who want to feel responsible without disruption. But entropy doesn’t care. Real sustainability would demand radical material restraint, cultural deflation, and systemic redesign. Instead, we’ve built a mood around a word. Thermodynamic, ecological, and political precision is what’s missing. Until then, sustainability is less a plan and more a sedative.

Some topics are tense. You can see the furrowed brows, darting eyes, and feel the crackle before the conversation begins. Already, you know that the balance between critical analysis and constructive engagement will be delicate.

Sustainability.

There, you felt it. The room inexplicably moves to the left and the right, the polemic silent but present, an elephant seal in a confined space. Mention sustainability, and everything becomes especially delicate.

The tension is eased a little with a reminder of sustainability’s conventional definition, which originates from the 1987 Brundtland Report by the United Nations. This definition frames sustainability as…

development that meets current needs without compromising the capacity of future generations to meet theirs.

Such a forward-looking ethic links environmental stewardship with social equity and economic viability. It implies and embraces a systems-thinking approach that integrates ecological health, human development, and economic resilience.

A system to ensure there is always a cake to eat when all our hard work deserves a treat.

At its core, this version of sustainability is built on the conviction that human well-being is fundamentally dependent on the health of natural systems. This belief acknowledges planetary boundaries as finite ecological limits, and it hints that entropy (the expression of the Second Law of Thermodynamics) is a real phenomenon, even for humans. Humans operate under the thermodynamic constraint that all systems require ongoing energy input to maintain order, meaning sustainability is less a state to achieve and more a process of continual energetic upkeep, bounded by the laws of physics.

‘Meeting future needs’ from the laws of thermodynamics makes the strongest case for preserving biodiversity, reducing pollution, and conserving resources such as water, soil, and energy. Simultaneously, it promotes social justice by advocating for equitable access to resources, opportunities, and decision-making processes. An ability to shape shared futures.

While interpretations and applications vary, the common assumption behind sustainability remains the creation of conditions in which humanity and the planet can thrive in the long term.

However, I've witnessed a fundamental problem in this environmental discourse throughout my career. There is a gap between aspirational language and transformative action. I think you know it. There is a disconnect between the lofty goals or commitments often expressed in policies, corporate statements, or public discourse and the meaningful, systemic changes that are actually implemented. While rhetoric may signal progress, it frequently lacks the power to challenge entrenched systems or deliver measurable impact.

There are plenty of instances, attempts, and genuine efforts to be sustainable from individuals, groups, and even whole towns. The occasional company even makes an effort. But structurally, for the general populace, is sustainability a paradigm to structure the social contract around? Not so much.

And this is an existential problem. In thermodynamic terms, social systems that aren't structured to renew complexity are bound to drift toward disorder, just as isolated systems succumb to entropy when energy inputs falter.

What if the real function of sustainability rhetoric isn't to enable environmental protection at all, but to sustain our current systems? The intent might be true, especially for individuals feeling their dissonance, as will the talk that eases that emotional discomfort. It could even be argued that sustainability is an idea that buys time for technological or social breakthroughs to emerge. For instance, somebody will invent fusion power to provide the energy essential to keep everything going.

Whether all the sustainability talk and no action is misguided comfort or necessary bridge-building might depend on whether such breakthroughs materialise and whether we have time to wait.

Something like there is a new Ye Olde Bakery coming to the high street, you know, where the tobacconist used to be.

Everyone talks a big game, but no one wants to say what sustainability actually means. It is time to take a scalpel to that comforting vagueness, exposing how the word has become a placeholder for virtue while dodging the hard questions. Real sustainability should be a reckoning. Saying the word out loud should force us to name what we’re trying to preserve, admit what we’re willing to sacrifice, and confront the systems that cannot be both comfortable and enduring.

It might even question the validity of cake in a healthy diet.

Let’s start with the premise that we lack a clear understanding of what sustainability entails…

The term 'sustainability' is now a dominant buzzword in politics, business, and culture that is used broadly but rarely defined with clarity or accountability.

The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that while 72% of Americans consider themselves "environmentally conscious," fewer than 30% can provide a coherent definition of sustainability when prompted.

The business world exemplifies this definitional chaos. Sustainability appears in corporate reports 340% more frequently than it did two decades ago, yet regulatory frameworks still lack standardised metrics for what constitutes sustainable practice. A 2023 study by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive found that among Fortune 500 companies claiming sustainable operations, 87% used different metrics to define their sustainability goals, making meaningful comparison impossible. Some companies measured carbon intensity per dollar of revenue, others focused on absolute emissions, while others emphasised recyclable packaging under the same sustainable business banner.

An academic analysis of sustainability discourse across policy documents, corporate communications, and media coverage revealed that the term functions more as what linguists refer to as a floating signifier. This is a word that carries emotional weight and social approval, yet lacks a fixed meaning. When meaning floats, it allows actors across the political and economic spectrum to appropriate the term without committing to specific, measurable outcomes.

Biodiversity is another good example of a floating signifier.

Sustainability gets a mention all the time, but it means what you want it to mean. Political speeches, corporate marketing, and academic papers all invoke the concept of sustainability with the ease of adding a slice of banana bread to your coffee order. Yet, when it gets real, there are endless disagreements about what we're trying to sustain and how we might measure progress.

And hardly anyone has an inkling of entropy’s tough truth.

Sustainability as a fuzzy floater has consequences that bring us to the second premise…

Vagueness in the use and definition allows a wide range of actors to adopt the language of sustainability without committing to meaningful change or measurable outcomes.

Organisational behaviour research confirms symbolic adoption, where institutions adopt popular terminology and frameworks without implementing substantive changes. A longitudinal study by MIT's Sloan School of Management tracked 200 companies that adopted sustainability reporting between 2010 and 2020. It found that 73% showed no significant change in resource consumption patterns despite extensive sustainability communications. These companies successfully captured the reputational benefits of sustainability rhetoric while maintaining business-as-usual operations.

Political science research reveals similar patterns in policy domains. Environmental economist Herman Daly's analysis of sustainable development policy frameworks revealed that governments often employ sustainability language to justify conventional economic growth strategies. The concept becomes what political scientists call a consensus concept, appealing precisely because it means different things to different stakeholders. A mining company and an environmental NGO can both support sustainable development while pursuing fundamentally incompatible goals.

I just call it an oxymoron.

Psychological research also demonstrates that individuals who engage in symbolic environmental actions subsequently feel permission to engage in more environmentally harmful behaviours. Buy a "green" product, get one free. This suggests that vague sustainability commitments may actually impede meaningful action, as all we need to do is feel good about it; no behavioural change is necessary.

When ExxonMobil launched its "algae biofuels" research program in 2009, the company invested $600 million over a decade while spending $3.5 billion annually on oil exploration. The biofuels research generated extensive sustainability communications and favourable media coverage, effectively deflecting attention from the company's core business model expansion. This pattern of small symbolic investments enabling large, unsustainable operations appears consistently across resource extraction industries.

Overall, multiple research domains confirm that definitional vagueness enables symbolic adoption without substantive change, often with counterproductive effects on genuine environmental action.

Here, have this doughnut. It has green icing.

All this may allow some smug CEOs to up their annual bonus, but there is a more insidious effect of psychological comfort described in the following premise…

The ambiguity of the term sustainability offers psychological reassurance, enabling individuals and institutions to feel responsible while avoiding discomfort or sacrifice.

Cognitive psychology research established that we use abstract concepts to manage anxiety about complex, overwhelming problems. For example, ethnographic studies of climate change response in Norway documented how communities embraced sustainability rhetoric as a form of socially organised denial. Participants in the survey expressed strong support for sustainability while dismissing specific policy measures that would affect their lifestyles.

Here is another example. Terror Management Theory, developed by Sheldon Solomon and colleagues, demonstrates that when people feel threatened by existential risks like environmental collapse, they gravitate toward cultural symbols and narratives that restore a sense of control and meaning. Sustainability rhetoric serves as a cultural worldview defence, helping to protect psychological well-being by suggesting that responsible action is being taken without requiring personal sacrifice or uncomfortable changes.

All cakes are good.

Studies by Yale's Cultural Cognition Project found that individuals presented with clear, specific environmental challenges experienced significant anxiety and defensiveness. However, when the same challenges were framed using sustainability language, emphasising gradual improvement and technological solutions, participants reported feeling more optimistic and less personally responsible for dramatic changes. This suggests that the sustainability discourse serves as an anxiety management tool, rendering serious environmental challenges psychologically tolerable.

Given these responses, it is no surprise that corporations use sustainability initiatives for similar psychological functions. Management scholar Joel Gehman's research on green organising found that companies often implement sustainability programs not primarily for environmental outcomes, but to maintain employee morale and organisational identity during periods of environmental criticism. Employees reported feeling more positive about their work at companies with visible sustainability initiatives, even when those initiatives had a minimal environmental impact.

We know that sustainability rhetoric serves essential anxiety-reduction functions that can impede confrontation with necessary changes. We like the feeling and have become addicted to sustainability in its vague form, which gives us the following premise…

In practice, many so-called 'sustainable' strategies maintain existing consumption, extraction, and inequality patterns under a green veneer.

A comprehensive study by the International Energy Agency found that while renewable energy installations increased 260% between 2010 and 2020, global energy consumption rose 18% during the same period, with fossil fuels still comprising 84% of total energy use. This pattern of absolute growth despite efficiency gains appears consistently across resource domains, suggesting that sustainability initiatives appear to enable rather than replace unsustainable practices.

The concept of sustainable intensification in agriculture, promoted by major agricultural companies and development agencies, promised to increase crop yields while reducing environmental impact. However, research by the University of Minnesota's Global Landscapes Initiative found that in practice, sustainable intensification typically involves increased input use, especially fertilisers, pesticides, and machinery, which may improve efficiency per unit of output but increase total resource consumption and environmental impact.

For me, it is another oxymoron.

Green growth strategies are another furphy. Efficiency doesn’t escape entropy; it speeds it up. Like adding fuel to a fire, increasing throughput without changing the system’s aim merely accelerates the burn. A meta-analysis of 835 studies by the European Environment Agency concluded that no country has achieved the level of resource consumption reduction necessary for global sustainability while maintaining economic growth patterns. Countries implementing green growth strategies typically improve their resource efficiency while increasing total resource consumption. This is Jevons Paradox named after the 19th-century economist who first documented how efficiency improvements often increase rather than decrease total resource use.

Oxfam's research on carbon inequality found that the richest 10% of countries account for 65% of consumption-based carbon emissions. This is quite the discrepancy. But the sustainability initiatives disproportionately focus on efficiency improvements that allow high-consumption populations to maintain their lifestyles. Meanwhile, World Bank data shows that 2.8 billion people still lack access to clean cooking fuels, and 760 million lack access to electricity.

Research indicates that sustainability initiatives often perpetuate or even exacerbate unsustainable consumption and extraction patterns, particularly when they fail to address questions of scale and distribution. Some of us are eating real and virtual cake every day and can’t wait for the Ye Olde Bakery franchise to open a store in our local shopping mall.

In short, sustainability isn’t cutting it, which brings us to the next premise…

Truly sustainable systems would require radical transformations, including rethinking economic growth, energy use, resource distribution, and societal values.

Planetary boundaries research provides the clearest evidence for this premise.

The Stockholm Resilience Centre's comprehensive analysis indicates that humanity has already exceeded safe operating limits for four of the nine planetary boundaries (climate change, biodiversity loss, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, and land use change), with others approaching critical thresholds. Calculations suggest that achieving global sustainability would require reducing per-capita resource consumption in high-income countries by 50-90% while improving resource access for the world's poorest populations, changes that are incompatible with current economic growth models and cake consumption.

Studies by the Institute for New Economic Thinking demonstrate that renewable energy systems, although essential, cannot simply replace fossil fuels without fundamental changes to energy consumption patterns. Limited substitution, combined with storage and transmission challenges, suggests that sustainable energy systems would require not just technological substitution but dramatic reductions in energy demand, particularly in high-consumption societies.

Ecological economics supports this premise. The aforementioned Herman Daly's work on steady-state economics and Tim Jackson's research on prosperity without growth demonstrate that sustainable systems would require abandoning GDP growth as a primary policy objective, implementing resource caps, and developing alternative measures of social progress. Jackson's mathematical modelling shows that any feasible rate of economic growth, when compounded over decades, generates resource demands incompatible with planetary boundaries.

But you don't really need complex modelling. Just gaze out the window on your next flight or train journey and imagine doubling what we have already done. That idyllic painting of Hampstead Heath couldn’t be replicated today. That ‘vale of health’ has buildings on it.

If the economics research sounds like bunkum, as it often can, social psychology research has demonstrated strong correlations between materialistic values and environmental degradation, as well as reduced well-being. Sustainable societies would require cultural shifts away from consumption-based status systems toward what psychologists call intrinsic values, typically of community, personal growth, and meaningful relationships. This aligns with anthropological research on past sustainable societies, which typically featured strong social institutions that limited individual accumulation and promoted resource sharing.

Our ancestors on the savanna did not eat cake.

All the serious research concludes that genuine sustainability requires system-level transformations that extend far beyond current policy approaches. Unfortunately, cake is not the foundation for a healthy diet.

So what is it precisely that we should sustain? Not knowing gives us the following premise…

The failure to confront what we are trying to sustain, be that lifestyles, ecosystems, economies, or power structures, limits our capacity for genuine progress.

Here is the contrary zinger.

Sustainability discourse avoids questions of power and distribution by framing the issue as a technical rather than a political problem. This approach, sometimes called post-political ecology, enables sustainability initiatives that address symptoms while preserving the economic and political structures that generate environmental problems in the first place.

Cake and eat it. Sorry, too much.

For example, sustainability communications often employ passive voice and abstract subjects, which can obscure agency and responsibility. Phrases like "emissions must be reduced" and "resources need to be managed sustainably" avoid specifying who should take which actions, effectively shielding existing power structures from scrutiny. This linguistic pattern appears consistently across corporate, governmental, and NGO sustainability communications. The blame game is a short step from this refusal to take responsibility.

There is also a status quo bias. Research on nature-based solutions has found that conservation initiatives routinely prioritise approaches that create new markets (such as carbon trading, ecosystem services, and sustainable finance) over approaches that would constrain market activities (such as resource caps, extraction moratoria, and consumption limits). More evidence for not confronting fundamental tensions between conservation and economic growth. I know this first hand as I pimped out my ecology skills to the carbon markets for a while.

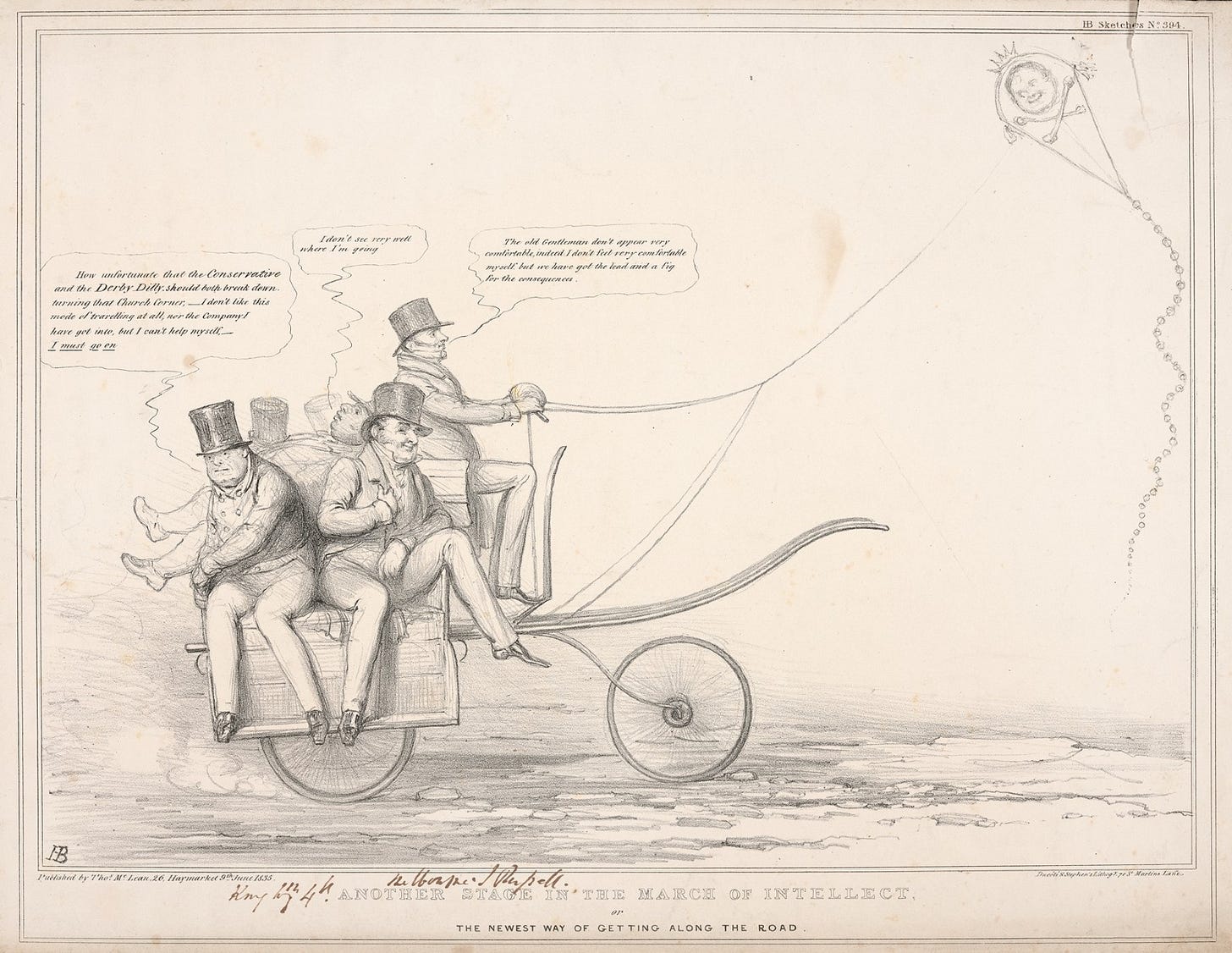

We are very good at this obfuscation and have been for a long time. Agricultural sustainability efforts in the 1930s Dust Bowl in the U.S. failed specifically because they avoided confronting the underlying economic structures driving soil degradation. Similarly, an analysis of Pacific Northwest timber policies reveals that ‘sustainable forestry’ initiatives have consistently failed to address the financial incentives driving overharvesting. These historical patterns suggest that avoiding core questions about what we're trying to sustain and at whose expense has been a persistent limitation of sustainability approaches for a long time.

It can be political ecology, communication studies, conservation biology, environmental history or any subdiscipline of your choice; they all avoid core questions about priorities and power structures that systematically limit the effectiveness of sustainability initiatives.

We are using sustainability to avoid sustainability.

This is cute and, for some, clever, but if the definition ‘meets current needs without sacrificing the capacity of future generations to meet theirs’ has any chance at all, then we need the final premise to hold…

Sharper, more honest language and frameworks that define sustainability in ecological limits, social equity, and long-term viability must replace aspirational branding.

Fortunately, there are alternatives to cake.

One alternative sustainability framework, the doughnut economics model (delicious irony), developed by Kate Raworth, provides concrete metrics that balance ecological limits with social foundations. Versions have been implemented in cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen, and initial assessments by Oxford's Environmental Change Institute suggest measurable environmental improvements compared to cities using conventional sustainability frameworks. This is largely because the doughnut model requires explicit confrontation with resource limits and social equity.

Precision and clarity in sustainability metrics can also produce better outcomes than aspirational frameworks. A study by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis compared the effectiveness of different sustainability measurement approaches across 150 cities globally. Cities using biophysical indicators (land use per capita, material footprint, carbon budgets) showed significantly greater environmental improvements than cities using composite indicators that combined environmental, economic, and social factors without clear prioritisation.

Precision applies to companies as well. MIT's Sloan School studies of corporate sustainability implementation found that companies using science-based targets (specific emissions reductions aligned with climate science) achieved substantially greater environmental improvements than companies using voluntary sustainability commitments. The conclusion was that science-based targets created external standards that enabled stakeholder evaluation, while aspirational commitments remained effectively unverifiable.

This can be happening to you right now. For example, hotel guests responded more strongly to specific requests ("reuse your towels to save 25 gallons of water") than to general sustainability appeals ("help us protect the environment"). Precise, honest frameworks not only enable better measurement but also motivate more effective action.

Do not eat that vanilla slice.

Research across multiple domains suggests that precise and honest sustainability frameworks yield better environmental outcomes than aspirational approaches, although the transition to such frameworks faces significant institutional and psychological obstacles.

We could do a lot better.

Sustainability isn’t.

It has become simultaneously ubiquitous and meaningless in public discourse. What we say about sustainability may not only be ineffective but also actively counterproductive, but it does provide psychological comfort that reduces motivation for necessary yet difficult changes. We like how it sounds as we continue to make more of everything.

All seven premises presented here hold when examined against empirical research, though, admittedly, with varying degrees of strength. The convergence of evidence across disciplines from cognitive psychology to biophysical sciences to political ecology suggests that being critical of how we use the term sustainability is not merely academic but identifies a fundamental obstacle to environmental progress.

The most compelling evidence stems from the disconnect between the psychological functions of sustainability rhetoric (anxiety reduction, moral licensing, symbolic adoption) and the radical changes that biophysical research indicates are necessary for genuine sustainability.

We are getting diabetes from all the cake.

Sustainability rhetoric is a sophisticated anxiety management system. The convergence of research from cognitive psychology, organisational behaviour, and environmental science suggests that this isn't accidental, but rather an emergent property of how humans handle overwhelming, systemic challenges.

The psychological research is particularly compelling. Moral licensing and terror management theory explain why vague sustainability language can feel so appealing, yet potentially be counterproductive. Our brains tend to overlook complexity, which is a standard lament of the mindful sceptic.

And yet, the biophysical evidence is stark. Planetary boundaries research leaves no wriggle room for incremental approaches. When Rockström calculates 50-90% reductions in high-income country consumption, he's not being dramatic; he's doing the math. We have several mindful sceptic guides that explore these biophysical limits.

The evidence also suggests that more precise and honest frameworks are both possible and more effective, although implementing them faces significant institutional and psychological obstacles.

The emergence of precise alternatives gives me hope. The Amsterdam doughnut economics implementation and science-based targets research suggest that when we get specific about what we're sustaining and at what cost, we make progress. We can return to a definition of sustainability that is closer to its original meaning, which is something that persists.

And in thermodynamic terms, to persist is to manage entropy through feedback, redundancy, and structures that channel energy wisely rather than wastefully.

However, all this suggests that we need intellectual honesty to reshape our approach to environmental challenges.

We have to be truthful. Mostly with ourselves.

When we define sustainability as something that persists, it forces us to confront energy, complexity, and feedback. It becomes less a virtue and more a function of thermodynamic discipline. The Second Law doesn’t negotiate. If our strategies require infinite substitution or behavioural stasis, they’re not strategies. They’re stalling tactics.

Entropy will collect the debt.

I think most people shy away from accepting the true meaning of sustainability because of the implications. Of course, it depends on the meaning but I take the basic meaning of being able to continue indefinitely. Of course, nothing can continue for ever (the planet itself has a lifetime) but if it cannot continue indefinitely, it will end.

For a way of life to continue indefinitely, two things must be true:

1. It must use no resource beyond its renewal rate.

2. It must not damage the environment beyond the environment's ability to assimilate the damage.

Number 1 means that no non-renewable resource can be used. Perfect recycling could enable some fixed size of economy to persist, as in steady-state. But perfect recycling is impossible. The easy to get minerals have been gotten. It now becomes harder and destroys habitat as it goes, transgressing the second rule, anyway.

Even renewable resources are currently being used at about, on average, 1.7 Earth's per year. Clearly unsustainable. Some countries are far worse than that, some use less than an Earth's worth but few people want to live like the average in those countries.

The conventional definition of not compromising future generations of the ability to meet their needs does get close. Obviously using more that a planet's worth of primary productivity is not sustainable and would compromise future generations. Using non-renewable resources would also compromise future generations, since it gets harder and harder to obtain those resources. But the word "need" requires definition. The only true needs are food, water and shelter.

True needs are met by a hunter-gatherer lifestyle (and, by all accounts, they were happy lives) and that is probably the only life-style that can be truly sustainable. This is why the word sustainable has been given so many definitions, definitions which stand some chance of keeping modernity sustainable. Except it isn't truly sustainable and, so, must end.