Overshoot Displacement Activity

Population Discourse Lets Us Dodge Ecological Reality

TL;DR

The stale binary of “population is a problem” versus “population isn’t a problem” is reframed through energy systems, ecological limits, and thermodynamics. From pre-agricultural times to the Green Revolution, modern population growth emerges not from human exceptionalism but from a temporary fossil energy surge. Technological advances have delayed collapse in some regions, yet planetary boundaries and entropy remain inescapable. Much of the population debate functions as displacement activity, allowing avoidance of the harder truth that civilisation rests on a one-off energy windfall. Replacing abstract headcounts with analysis of energy flows, carrying capacity, and systemic resilience is essential to confronting the limits that shape our future.

I am a population ecologist. Well, I used to be, for ‘woodlice numbers’ is where I began my ecological career. How many were there in the chalky grasslands of eastern England, and could they regulate their numbers as the theory of density-dependence said they should? After a PhD's worth of research, I said that they could. It was a brave assertion, very Malthusian.

When a post-doctoral scholarship took me to Zimbabwe, I was distracted by termites, millipedes, the occasional elephant and especially how organisms contributed to soil fertility. And because soil biology was a systems problem, I drifted from population ecology and was eventually captured by biodiversity, the trendy new topic of the mid-1990s. My woodlouse research continued, but it found new hypotheses to test in evolutionary ecology, specifically whether a female woodlouse should invest in fewer large or many small offspring, and provided any insights into population dynamics through this proxy.

Hindsight tells me that this was fortunate because of population, a word that in my time was a neutral descriptor in demography and planning had acquired a controversial edge, especially in environmental and political discussions. Historically linked with Malthusian warnings about overpopulation and famine, it became a shorthand for fears that rising human numbers would outstrip Earth’s resources.

These concerns resonated during the 1960s and 70s in popular works like The Population Bomb, and it didn’t help that I met and liked its author, Paul Ehrlich. Partly as a consequence of these warnings, ‘population’ now carries undertones of racial and geopolitical bias, often targeting growth in the Global South. As a result, the word now evokes not just demographic concerns, but ethical debates around power, control, and whose lives are deemed burdensome.

In politics, population surfaces in debates about immigration, housing, and infrastructure, often serving as a coded term for social unease or xenophobia. In countries like Australia, the UK, and the US, concerns about ‘population pressures’ tend to mask deeper fears about changing demographics, economic insecurity, or cultural identity. More than one white man is scared of being in the minority.

Like many scientifically neutral terms, including biodiversity, sustainability, ecosystem services, and resilience, the term population is now an ambiguous floating signifier. It means whatever is on your mind. More often than not, the resource constraint debate becomes a binary issue between "population is a problem" and "population is a boon".

It is a risk to speak constructively about population today. Somehow, you must be sensitive to historical misuses and more than a little woke, making sure rights-based, equitable, and context-specific perspectives are given plenty of attention. Even then, you will get flamed by either side for no reason.

Even speaking the word requires courage. It’s not the number of people that scares us, it’s what counting them forces us to admit about how we live.

But before I dust off my PhD thesis and tackle human numbers with the objectivity of a population ecologist, I do need to remind you of a few details.

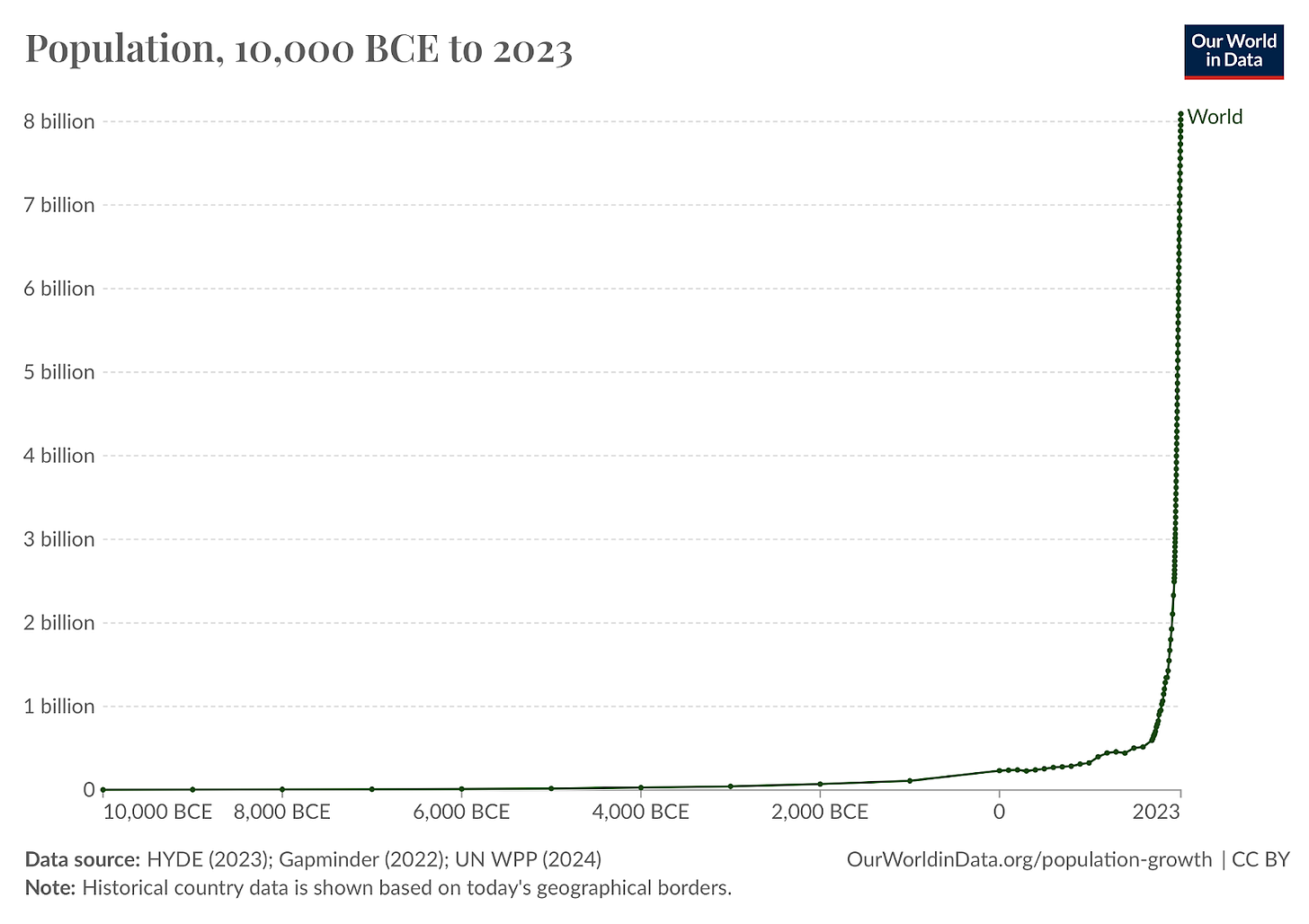

For around 290,000 years, Homo sapiens were few, perhaps 10 million across the world and often fewer, into the tens of thousands at times.

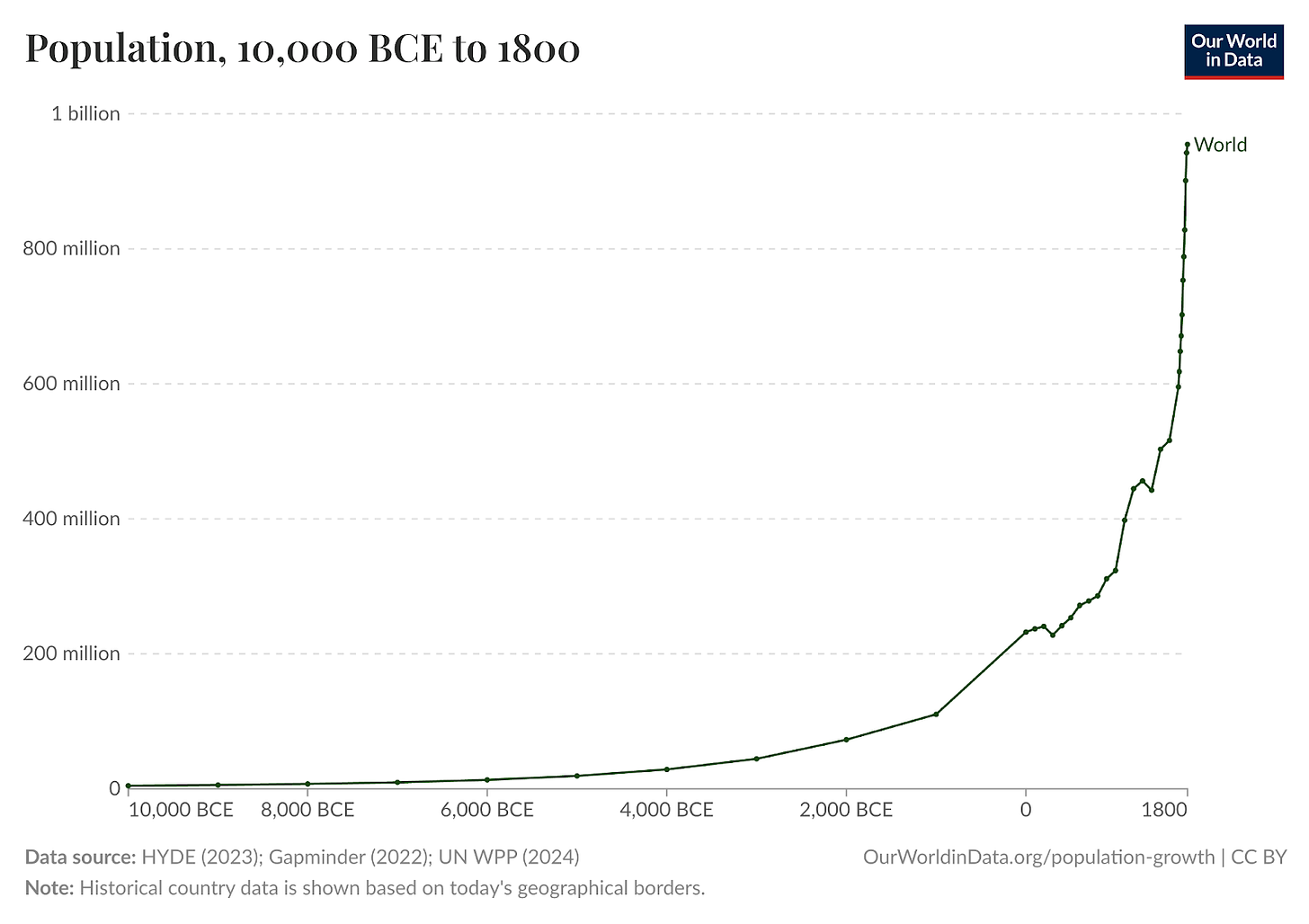

When we cleverly invented agriculture 12,000 years ago, there were 5–10 million people mainly in Asia. …that is million with an “m.”

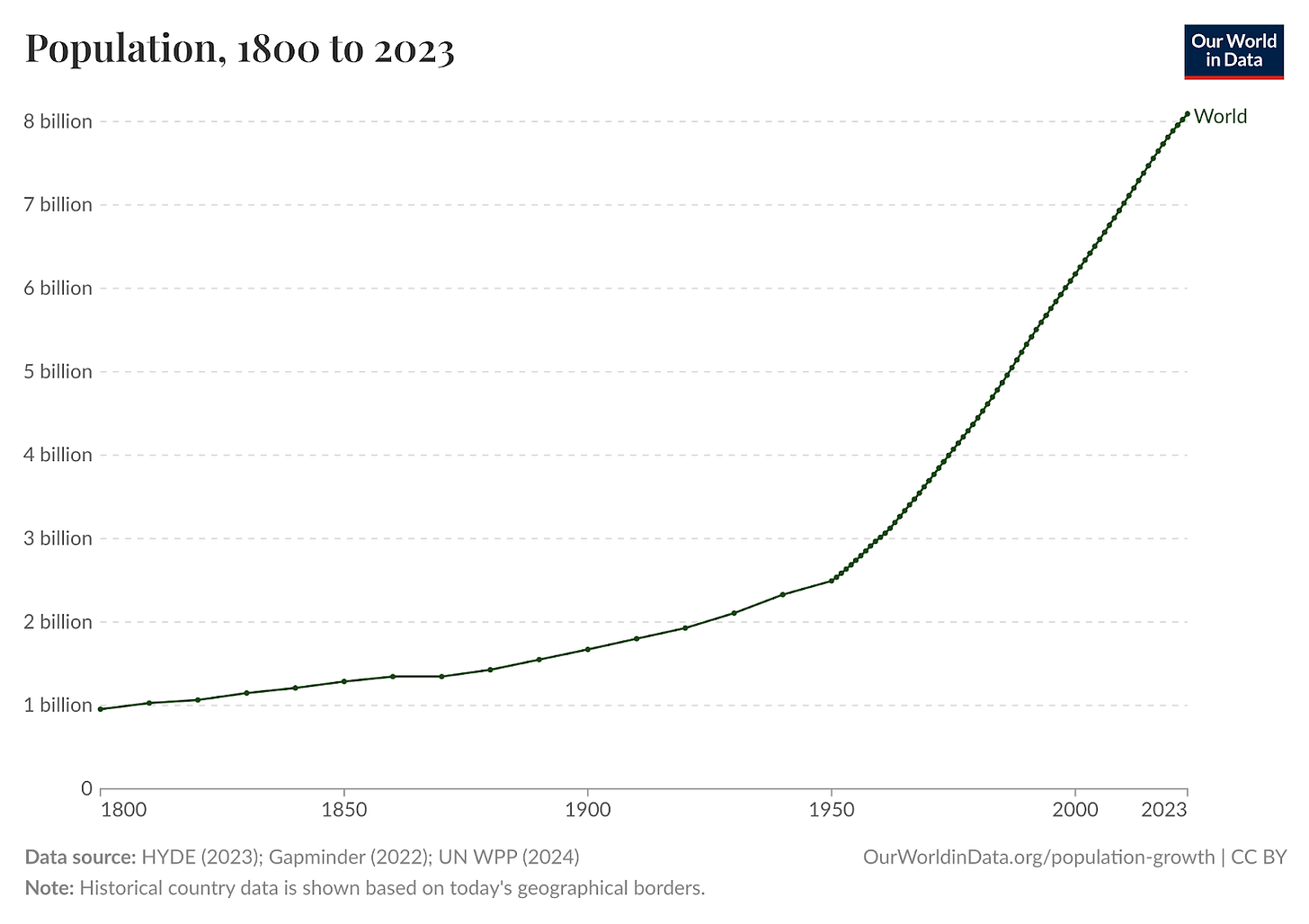

Agriculture gave us an energy boost, and we increased in number to 1 billion by 1800, an exponential increase to 1,000 million with an exponent that would have seen 2 billion by 2025 if it had followed the historical trend. It didn’t because we cleverly found fossil energy and ploughed it, quite literally, into the intensification of agriculture, which in less than 200 years created a highly efficient global food system that, along with some clever healthcare, produced a population spike.

Since 1800, the population has quadrupled to 8.1 billion by 2025. That is 8× more people in 7 generations.

A population over 8 billion requires a minimum of 23 trillion kilocalories per day in food energy just to stave off hunger.

Contrary to popular opinion in the global north, where the demographic transition has led to lower fertility and, for some countries, negative population growth, the global numbers are still rising at 8,000 an hour. In a year, the net increase in the global population is about 70 million, many times more than the total population 12,000 years ago.

Now that you have the population consequences of a fossil energy pulse to hand, there is one more detail before the first premise.

What looks like an orderly leap in capacity is, in thermodynamic terms, a spike in the rate of energy dissipation. Agriculture didn’t just feed more mouths; it pushed more low-entropy sunlight through human systems at a speed nature hadn’t budgeted for, accelerating the disorder we’d later have to reckon with. In thermodynamic terms, every added calorie of low-entropy input not only builds temporary human order but also hastens the breakdown of the wider ecological order. The faster we run energy through our systems, the quicker we strip away the gradients that make life possible.

So here is the first premise…

The dominant population-resource narrative is rooted in Malthusian assumptions that no longer reflect current technological and social realities.

The classic narrative, originating with Thomas Malthus in the late 18th century, posited that population growth would inevitably outstrip food supply, leading to widespread famine and societal collapse. This assumption was based on Malthus’ idea that populations grow geometrically while resources, particularly food, increase only arithmetically. Malthusian ideas, both for and against, have dominated population discourse for over two centuries, influencing everything from colonial policies to modern environmental movements.

At first glance, Malthus got it wrong. Historical data reveal a profound disconnect between Malthusian predictions and reality. The global population has increased from 1 billion in 1800 to nearly 8 billion today, largely due to improvements in per capita food availability.

You can't have exponential population growth in any animal without an excess of food because, without food, the animal dies or its offspring do. It can't make its own energy. Apologies for being trite, but it is fundamental to any understanding of density dependence.

The Green Revolution of the 1960s-80s exemplifies how technological innovation shattered Malthusian constraints. High-yielding crop varieties, combined with synthetic fertilisers and improved irrigation, increased cereal production by 250%. Countries like India and Mexico, once facing predicted famine, became food exporters.

Not only was more food grown, but it was also harvested, processed and transported to where people lived, over 50% of them in urban areas. With the help of exogenous energy, human ingenuity could fundamentally alter the population-resource equation through institutional changes, knowledge transfer, and coordinated global action.

And then there was a demographic transition.

In some countries, urbanisation, women's education, access to healthcare, and economic development contributed to a slowing of population growth into a demographic transition. At the same time, resource use became more efficient, and innovations in recycling, synthetic biology, and renewable energy suggest that absolute scarcity is not a given. As such, the simplistic equation of more people equals less to go around no longer captures the nuanced dynamics at play in modern systems.

The seductive demographic transition theory suggests that development typically leads to lower birth rates, not resource collapse. Studies by demographers like Hans Rosling demonstrated that the relationship between population and well-being is mediated by factors Malthus never considered, including education, healthcare systems, economic institutions, and social cooperation. And where the Malthusian narrative of resource constraint persists in climate discussions, migration debates, and conservation efforts, it is heavily criticised for ignoring the institutional and technological transformations of the past two centuries. The evidence is that simplistic population-pressure assumptions are unrealistic. It is remarkable what can be done with a six-continent supply chain.

However, dismissing the Malthusian perspective entirely would be premature. While we have mostly avoided the famines Malthus feared, the unsustainable overuse of ecological resources, biodiversity loss, and climate change reveal that technological progress alone cannot decouple human activity from environmental impact. There is an energetic and a resource degradation cost of 8 billion souls and their livestock.

Many recognise these consequences and decide to shift the population issue to be less about the number of people and more about patterns of consumption, inequality, and the biophysical limits of certain ecosystems. Thus, many consider the Malthusian model to be obsolete as a universal law, but it might retain analytical value, especially to help understand the uneven distribution of risk.

Not that it ever was a law. Malthusian assumptions have indeed been repeatedly contradicted by historical experience. The number of people has risen to levels that Victorian gentlemen could have barely imagined. And with the demographic transition kicking in to slow population growth, the new conventional wisdom on population is captured in the following premise…

Technological innovation and institutional complexity have largely decoupled population size from direct resource scarcity in many global contexts.

Since 1961, when I was born, global cereal yields per hectare have increased by over 180% while the total harvested area expanded by only 12%. This means the global food system is feeding nearly three times as many people using roughly the same amount of farmland. Clearly, population growth does not ‘inevitably outstrip food supply,’ and thus, it doesn't automatically translate to proportional resource pressure.

The Netherlands has one of the world's highest population densities of over 400 people per square kilometre. Yet, it's also the world's second-largest agricultural exporter by value, achieving this through advanced greenhouse technologies, precision agriculture, and sophisticated logistics.

Modern global trade networks allow regions to specialise based on comparative advantage rather than attempting local self-sufficiency. Singapore, with virtually no natural resources and extreme population density, maintains one of the world's highest living standards through strategic positioning in global supply chains. Similarly, urban planning innovations have enabled cities to house billions efficiently. Manhattan, for example, supports a population density of over 25,000 people per square kilometre while providing access to resources that would be impossible in dispersed rural settings.

The knowledge economy represents the most profound decoupling. Software, finance, and creative industries conjure extraordinary wealth from almost nothing tangible. Each innovation, such as GPS, the internet, and blockchain, can ripple across countless domains, reducing resource use while sustaining ever larger populations. Romer’s growth theory shows how ideas, not acres or ores, can fuel compounding productivity. Cleverness becomes capital.

But the illusion has ballast. The cloud is a warehouse of servers, each gulping coal-fired electricity and laced with rare earths torn from fragile soils. Digital tools save paper and airfares, but they also spawn e-waste mountains and train energy-hungry models that consume more watts than entire nations. Every ‘weightless’ app rides on a heavy infrastructure of extraction and entropy.

Any apparent decoupling isn’t complete or universal. Many rural agricultural communities remain closely tied to local resource availability, as shown during COVID-19 when lockdowns caused labour shortages, transport delays, and market disruptions that directly impacted food production. Even in wealthier countries, local and regional food systems proved critical, with U.S. producers adapting more nimbly than national supply chains. At the same time, disruptions to labour, logistics, and just-in-time manufacturing cascaded into widespread shortages, revealing how institutional complexity can rapidly turn into institutional vulnerability.

However, from a population perspective, decoupling appears as real and significant in many contexts, particularly in urban and developed economies.

Over the past century, conventional thinking among economists, demographers, and development theorists has shifted. It used to be rigid population-resource determinism where there were perceived limits. Now thinking is dominated by technology, markets, and institutions in shaping resource availability. Technological innovations and strong governance structures, trade networks, property rights regimes, and regulatory frameworks are expected to allow for more effective resource management and distribution. For example, international grain markets can compensate for localised droughts, and energy grids can stabilise supply despite regional variability in renewable generation. If you or your country has money to buy, there is a producer willing to sell.

Not everyone is free of resource scarcity.

There remain over 750 million people in extreme poverty. That is one in eleven humans and an acute reminder that, for all our cleverness, progress leaves almost a billion people outside the story we like to tell ourselves. So while the conventional wisdom affirms the power of innovation and institutional resilience to mitigate scarcity, it also increasingly recognises the importance of equity, ecological boundaries, and systemic risk.

Most techno-optimists generally hold that science, innovation, and adaptive systems can solve or sidestep many of the environmental and resource limitations that once defined human existence. They point to history and argue that any constraints imposed by nature are challenges to be solved rather than permanent barriers to growth or wellbeing. This mindset sees nature not as an immutable ceiling but as a dynamic set of parameters that can be reshaped through knowledge, engineering, and institutional evolution. For instance, scarcity of arable land may be met with vertical farming or lab-grown meat; freshwater limitations may be solved through desalination and smart irrigation; and fossil fuel constraints bypassed by solar panels, batteries, and fusion research.

In this view, nature provides the canvas, but human creativity offers the tools for constant reconfiguration. As a result, techno-optimism often places its faith in innovation outpacing degradation, and in the resilience of systems engineered by humans. In this view, Malthus overlooked the cleverness of people.

But what if we underestimate ecological feedbacks, tipping points, and the complex interdependencies of natural systems? What if the urgency of living within biophysical thresholds is prudent risk mitigation against the assumption that future breakthroughs will arrive in time?

Here we reach the alternate premise to technological innovation…

Despite technological advances, human societies remain ultimately constrained by ecological limits and planetary boundaries that cannot be indefinitely transcended.

Population ecology is all about the dynamics of species populations and how these are influenced. First of all, the population is the unit of study defined as a group of individuals of the same species occupying a defined area and capable of interbreeding. A population ecologist measures the attributes of population size, density, age structure, birth and death rates, immigration and emigration, and sex ratio to determine and understand how populations change. Often, this information feeds into population growth models, such as exponential and logistic growth, which describe how populations expand under ideal or constrained conditions.

Population ecology examines not just isolated species but how they interact with other species and within food webs through competition, mutualism, predation, or parasitism, not least because these interactions are often the source of impact factors.

A few features are consistent with all populations of any organism.

Populations are impacted by density-dependent factors (e.g., competition, predation, disease) that intensify as population size increases, and density-independent factors (e.g., climate, natural disasters) that impact populations regardless of size. They are ultimately constrained by resources, be that food, space, access to light, water or some critically limiting requirement. In times of plenty when it can seem like a population will grow forever, they never do because, ultimately, the planet is finite. Soon enough, the Water Lily runs out of surface water in the pond.

The reality of an upper limit to population size brings in the concept of carrying capacity, or the maximum population size an environment can sustain over time without degrading the resource base. It suggests there is a clear, quantifiable limit to growth in a complex world. People like this idea because it echoes our desire for predictability, control, and moral boundaries. And a maximum number of individuals an environment can support resonates with intuitive notions of balance and sustainability.

This is population ecology, the integration of empirical observation and mathematical modelling to reveal patterns and processes that govern how life persists and fluctuates. A population ecologist’s role is to predict population stability, boom-bust cycles, or extinction risk.

Still, I have to say that we are easily suckered into the idea that population is regulated. We can easily imagine that these factors combine in some way to keep populations at or below that carrying capacity.

Human populations are no different to any other species. We have always been constrained by the carrying capacity of the habitats in which we lived. This was a heavy constraint for over 290,000 years of foraging on savannas, next to rivers and lakes, or coastal fringes. Agriculture increased the capacity by making more calories available overall and for safe storage of calories during lean times. Livestock was a terrific boon as a larder that kept itself fresh.

But then, almost overnight, we were no longer constrained.

Fossil fuels, combined with technology, have increased the human carrying capacity to such an extent that its exact location remains unknown. From a complexity perspective, this is less a permanent elevation and more a high-wire act. Systems bloated on fossil calories become more intricate but also more brittle, because every new layer of complexity requires constant, high-quality energy to hold its shape against entropy’s pull. In this sense, complexity buys time but not immunity. The trick is to build complexity that can persist within nature’s energy budget, rather than one that collapses the moment the fossil subsidy is withdrawn. Nonetheless, some think carrying capacity has been lifted out of existence, and we are no longer animals. However, the planet is finite. There is only so much space, so much net primary production, so much fresh water, and so much available nutrients. There are physical and ecological limits.

The planetary boundaries framework, first developed by Johan Rockström and colleagues in 2009 and updated by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, provides scientific grounding for these absolute ecological limits. The research identifies nine Earth system processes that regulate the stability and resilience of our planet, giving nine defined environmental limits beyond which Earth’s life-support systems risk destabilisation. These boundaries represent thresholds that, if crossed, could lead to irreversible ecological change and are intended to define a ‘safe operating space for humanity’.

The nine planetary boundaries are:

Climate Change – Maintaining atmospheric CO₂ levels and radiative forcing within limits to avoid runaway global warming.

Biosphere Integrity (Biodiversity Loss) – Preserving genetic diversity and ecosystem function to maintain resilience and life-support capacity.

Biogeochemical Flows – Managing nitrogen and phosphorus cycles to prevent eutrophication of water bodies and soil degradation.

Land-System Change – Avoiding excessive deforestation, urban expansion, and land conversion that disrupt ecological processes.

Freshwater Use – Ensuring sustainable consumption of surface and groundwater to maintain hydrological systems.

Ocean Acidification – Limiting CO₂ absorption by oceans to protect marine ecosystems and carbonate chemistry.

Atmospheric Aerosol Loading – Controlling particulates that affect climate, monsoon systems, and human health.

Stratospheric Ozone Depletion – Preventing loss of the ozone layer that shields life from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Introduction of Novel Entities – Regulating synthetic chemicals, plastics, nanomaterials, and genetically modified organisms whose long-term effects are largely unknown.

As of the latest assessments, boundaries for climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows, and land-system change have already been crossed, indicating that humanity is operating in a zone of increasing risk.

The strength of the framework lies in its systems-based approach, linking environmental integrity to human prosperity and signalling that sustainability is not merely a social or economic issue, but a biophysical necessity. And unlike local resource constraints that technology can often overcome, these represent system-level limits that affect the entire Earth system.

Let’s make this more practical.

Climate change is the boundary that exacerbates all other boundaries. Breach it, and the stress ripples outward, weakening ice sheets, raising seas, pushing weather into chaos. We’ve already warmed the planet by over 1.1°C since pre-industrial times through fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and industrial emissions. These aren’t gentle changes. They’re non-linear, hard to reverse, and capable of triggering cascading crises in food, water, and political stability. Cross thresholds like permafrost thaw or Amazon dieback, and you set feedback loops in motion that no amount of negotiation or geoengineering can easily stop. Perhaps they cannot stop them.

Efficiency gains haven’t slowed the curve. Annual fossil fuel burning still pours more than 35 billion tonnes of CO₂ into the air. Now atmospheric concentrations are above 420 ppm and way past the pre-industrial 280 ppm. This forces more extreme weather, accelerates glacial melt, and lifts sea levels. The scale of our economy keeps outrunning the speed of our efficiency just as William Jevons predicted way back in 1865.

The Second Law ensures that every “efficiency” is only a reprieve if total energy flow increases; the faster we cycle energy through our systems, the quicker we degrade the gradients that keep them running. What looks like progress on the spreadsheet can, in physical terms, be a faster burn of the same candle. Without capping total energy flow, efficiency becomes a sleeker engine for accelerating disorder.

Meanwhile, energy return on investment (EROI) puts a hard limit on our options. Renewables keep improving, but building, installing, and maintaining them takes energy and materials. Charles Hall’s work suggests civilisation needs an EROI of at least 3:1 to keep basic systems running and closer to 7:1 to sustain a complex global economy. Thermodynamics doesn’t care how clever we are because there’s a floor below which systems can’t function.

Biodiversity loss is another slow-burn collapse with fast-burn consequences. Extinctions, habitat fragmentation, and genetic erosion weaken the very networks that keep ecosystems stable. A loss of pollinators, soil microbes, or keystone predators reduces resilience. The extinction rate today is hundreds of times the natural background, signalling a mass extinction in progress. This isn’t just about saving pandas, however cute they might be. This is about protecting the living systems that underpin our food, health, and planetary stability.

The nitrogen and phosphorus cycles are being pushed beyond safe limits, mainly by industrial agriculture. Human activity now releases more reactive nitrogen than all natural processes combined. Fertiliser runoff creates aquatic dead zones, degrades soils, and adds nitrous oxide to the atmosphere. These nutrient cycles connect directly to water use, land change, and ocean health, and they’re being breached faster than most others. Reversing them is challenging because industrial farming is heavily reliant on fertilisers.

And then there’s the quiet boundary most people miss, but any population ecologist recognises in an instant: land degradation. The FAO estimates we lose 10 million hectares of arable land every year, an area the size of South Korea. Technology can boost yields, but often by stripping soil nutrients faster than nature can replace them. It’s the thermodynamic truth of agriculture that you can mine the land for a while, but you can’t break the energy and material laws that govern it. Over-fertilisation drives more nitrogen and phosphorus into rivers and lakes, fuelling algal blooms and creating hypoxic dead zones, like the one in the Gulf of Mexico.

The obvious conclusion to all of this is that there are limits and there is a carrying capacity to human population defined by the ecological consequences of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which succinctly says that nothing can deny entropy. Life doesn’t escape entropy; it amplifies it. Every calorie we channel into sustaining human order, whether in skyscrapers, spreadsheets, or soybeans, multiplies the disorder elsewhere in the system. The only game is pacing that dissipation, so the structures we depend on don’t unravel faster than we can adapt.

However, this is highly inconvenient to humanity, which consists of sentient beings capable of perceiving their mortality, having a brain wired for survival on the savanna, where the desire to acquire, possess, and hold more resources was an evolutionary advantage.

The simple solution is to ignore the demographic facts. Hence, the following premise…

Perceptions of population pressure are shaped more by political, cultural, and economic structures than by demographic facts, with overpopulation narratives often obscuring deeper issues of inequality and consumption patterns.

Population has become the conversation no one wants to have. In academic and environmental circles, even hinting at a link between population and sustainability risks being branded as neo-Malthusian, racist, or misanthropic, sometimes all three and more. Yet we know that voluntary reductions in birth rates in developing countries improve women’s lives, expand economic opportunities, and ease pressure on resources. Feminist scholars are right to warn that population narratives have often been tools of control, deciding whose bodies are deemed “surplus” and whose reproduction is sanctioned.

The politics of population is rarely about numbers alone; it’s about power. Environmental sociology shows how international development agencies historically pushed population control in the Global South while ignoring the vastly higher per-capita consumption in the Global North. A person in the richest 10% consumes around 25 times more resources than someone in the poorest 50%. Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute found that the wealthiest 10% generate almost half of all carbon emissions, while the poorest half contribute less than 10%. In energy, water, and material use, the pattern repeats. In 2020, Oxfam reported that the richest 1% had per-capita emissions more than 30 times higher than the level compatible with 1.5°C climate targets. Yet public discourse keeps circling back to birth rates in poor countries, because it’s easier to talk about African fertility than Western overconsumption.

History makes the pattern unmistakable. Population concerns spike during periods of economic stress, usually aimed at controlling marginalised groups. The eugenics movement in early 20th-century America targeted what they called “undesirable” populations even as growth rates were already falling. Today, anti-immigration rhetoric uses overpopulation language during recessions, regardless of actual demographic data. Jennifer Reid Keene’s research shows how this language is a socially acceptable proxy for talking about race, class, and national identity without naming them. Beneath all this is a deeper cultural anxiety about modernity, autonomy, and control.

Anthropologists note that fertility fears often mask discomfort with changing gender roles and the erosion of traditional power structures. Psychologists call it pseudo-certainty, the comfort of pretending complex, messy problems can be solved with a single neat number. Count the people, cut the number, problem solved. It’s an illusion, but one that keeps returning because it offers both a target and a sense of control.

Once you buy into a social perspective on population, it becomes even easier to ignore the demographic facts. Now it is not a resource limit problem but a social equity challenge, and we arrive at the following premise…

Sustainable futures depend more on how populations adapt, cooperate, and distribute resources than on their absolute size.

Complex adaptive systems theory tells us that population isn’t just about headcounts because in all ecological systems that include the human one, small changes can trigger big, non-linear shifts. And the data are unambiguous. Wealthy industrial nations burn through far more resources per person than poorer ones, regardless of their population density. That makes consumption patterns, not raw numbers, the real driver of ecological pressure.

Resilience science backs this up. What matters most for sustainability is the ability of institutions, communities, and ecosystems to learn, self-organise, and respond flexibly to change. In complex systems terms, such adaptability spreads energy dissipation across many pathways, preventing any single shock from cascading into full collapse. Diversity and redundancy are essential thermodynamic stabilisers. Because of this adaptive capacity, a high population does not automatically mean collapse, but poor governance and rigid systems almost guarantee it. The real test is whether a society can manage change, share authority, and align incentives with long-term survival.

Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) provides powerful evidence. From Nepal’s forest commons to fisheries in the Philippines, small, cohesive, well-organised groups routinely outperform larger, more fragmented ones on conservation and fair resource use. Success depends not on the number of people but on the quality of governance that covers trust, accountability, local knowledge, and inclusive decision-making.

Elinor Ostrom’s groundbreaking work proved that the tragedy of the commons is not destiny. When communities have clear boundaries, participatory rules, conflict resolution, and local enforcement, they can manage shared resources sustainably for generations. Population size or density alone tells you nothing. What matters is the fit between social systems and the ecosystems they depend on. Similarly, Costa Rica, with a population density similar to many African countries, protects biodiversity and fosters sustainable development through strong institutions, education, and democratic governance. Meanwhile, countries with low density, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, can still see catastrophic resource loss when governance fails, inequality grows, or conflict takes hold.

Climate adaptation research finds the same pattern. Resilience depends on social capital and cooperation. After Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans neighbourhoods with strong local networks and active leadership recovered faster than similar areas without them. In shocks and crises, it’s social cohesion that tips the balance.

Cooperative networks also spread sustainable practices far faster than top-down interventions aimed at population numbers. In Central America, the farmer-to-farmer movement has carried agroecological techniques to millions of small farms through peer learning, adapting innovations to local conditions. Development economists like Esther Duflo confirm that these social learning effects often outweigh demographic factors entirely.

This brief foray into social cohesion suggests that it is easy enough to find evidence that social organisation, cooperation, and adaptive capacity are more important determinants of sustainability outcomes than absolute population size. And for the moment, we will ignore the scale mismatch between these localised examples and the global boundaries.

Given that population is as much a people problem as it is the number of people, the following premise is both logical and necessary…

Moving beyond numerical reductionism requires new frameworks that prioritise resilience, justice, and regenerative capacity over conventional metrics like population growth and GDP.

GDP and population growth make for neat, comparable numbers, but they strip the story down to what can be counted and miss what matters. GDP logs every transaction as positive, whether it’s a productive investment or rebuilding after a disaster, and ignores whether the gains are equitably shared, ecologically destructive, or even sustainable. Population totals do the same. They count heads but skip the harder questions about how people live, consume, govern, and adapt. This numerical reductionism gives the illusion of precision while dodging the systemic and ethical complexity of sustainability and even the consequences of the energy needed to defy entropy.

Resilience frameworks turn the lens toward the ability of systems to absorb shocks, adapt, and still hold their core identity. Drawing from ecology, systems theory, and institutional economics, they focus on feedback loops, thresholds, diversity, and redundancy. Scholars like Brian Walker and Carl Folke have shown that resilient social–ecological systems can survive disruption without losing function. The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities program puts this into practice, developing tools that measure resilience across multiple dimensions instead of relying on a single growth metric.

Climate and environmental justice movements add another essential layer to understand who benefits and who pays. Those least responsible for ecological damage often carry the heaviest burdens. Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum’s capabilities approach shifts the question from “How much do you have?” to “What can you actually do and be?” It shows that flourishing doesn’t always require resource-heavy development models. Environmental justice research warns that sustainability efforts often fail when they deepen existing inequalities or push costs onto vulnerable groups.

Regenerative development goes further, rejecting the extractive assumption that natural and social systems are limitless inputs. Carol Sanford and others argue for development that actively improves the health of the systems it touches. Regenerative agriculture builds soil, boosts biodiversity, and restores water cycles while producing food and creating positive feedback loops instead of linear depletion. These approaches require metrics that track system vitality, rather than just throughput or growth rates.

The shift isn’t hypothetical. It is visible in policy experiments, academic research, and grassroots movements worldwide. We know that conventional metrics can’t capture the complexity of sustainability, and alternative frameworks already exist that measure what actually matters. The challenge is not inventing them, but having the courage to replace the comfortable fictions of growth and headcounts with measures that reflect the real conditions for long-term survival.

All this moralising is understandable.

Evolutionary biology, developmental psychology, and cross‑cultural research converge on the fact that humans likely come equipped with a deep-seated aversion to inequity, especially when we're at a disadvantage. In the animal world, this is far from unique. Capuchin monkeys, for instance, famously reject unequal rewards, throwing away cucumbers if their neighbour gets a grape for the same effort, even refusing to trade at all. Broader studies show this disadvantageous inequity aversion in chimps, macaques, ravens, and dogs, suggesting it evolved to safeguard cooperation against exploitation.

Human infants as young as 15 months gravitate toward fair resource distribution, and by age 4, children begin rejecting scenarios where they receive less than their peers. This emerges consistently across cultures and is a near universal among children. Advantageous inequity aversion which means turning down extra for the sake of fairness, appears more selectively, shaped by cultural norms.

Disliking inequity is one thing; prioritising resilience, justice, and regeneration is another. Our instinctive fairness responses are often short-term, reactive, and self-focused. We’re quick to call a foul when we lose, slower to act when we win. Inequity aversion can be drowned out by loyalty to our in-group, fear of loss, or faith in meritocracy. In complex, hierarchical societies, injustice can be institutionalised and hidden, making it easy to ignore when it benefits us.

The implication from psychology is that if we want resilience, justice, and regenerative capacity, we can’t rely on instinct. Resilience demands long-term thinking, systems awareness, and comfort with uncertainty. These are traits that human cognition tends to resist. Justice requires accountability, representation, and redistribution. A prod in the direction of doing the right thing will not be enough.

For example, regeneration will mean redesigning economies to work with ecological limits instead of mining them for short-term gain, which is a cultural and structural pivot of historic scale. None of these are intuitive defaults. They are collective, intentional choices that often cut against immediate self-interest.

In other words, any realistic alternative to Malthusian population-resource ideas will need to exist within the planetary boundaries and explain how we might flourish there without the need for the abomination of demographic control.

So we reach the last premise…

Reimagining the population-resource relationship reveals pathways that emphasise human flourishing within planetary boundaries rather than demographic control.

The traditional population–resource framing is crude. It assumes that more people mean fewer resources, more scarcity, and inevitable ecological decline. From there, it’s a short leap to the politically toxic idea that controlling fertility or immigration is necessary. Yet for the last 200 years, the worst predictions of environmental Malthusianism never came to pass. In the aggregate, technological innovation and social adaptation kept supply ahead of demand. The conclusion, for many, was that population isn’t the problem after all.

That verdict ignores the complexity of the system. Population pressure interacts with consumption patterns, inequality, governance, and fossil energy. Without cheap, abundant fossil fuels, the last two centuries’ growth trajectory would look very different. Any polarised population debate of too many or not enough dodges an uncomfortable truth. Eventually, resources will constrain us. And you don’t need to be a population ecologist to know what happens when demand overshoots supply.

A better frame shifts the focus from headcounts to how we live, how resources are shared, and what we value as progress. Policies that expand education, health, gender equity, and participatory governance tend to lower fertility rates without coercion and build resilience at the same time. This is population policy by stealth, creating the conditions where smaller, healthier families are the natural choice.

This reframing aligns with the planetary boundaries framework, where ecological limits aren’t shackles, they’re the conditions for lasting prosperity. A small but wasteful population can do more damage than a larger one living regeneratively. If we focus on flourishing as quality of life, equity, health, education, and strong communities, then we can design development paths that are both humane and ecologically safe.

Living regeneratively also sidesteps the ugly history of demographic control and the ugly mechanisms of coercion, racialised targeting, and disregard for human rights. Instead, it emphasises agency, justice, and systems thinking. Sustainability isn’t about limiting people; it’s about redesigning how we inhabit the Earth. The result is a more sophisticated, ethical way to navigate the population–environment nexus in the 21st century.

Wellbeing economics shows that high life satisfaction is possible at far lower resource use than conventional development assumes. The Happy Planet Index finds countries like Costa Rica and Vietnam delivering strong wellbeing with ecological footprints near sustainable levels, while the United States consumes 4–5 times more resources per capita for only marginal gains in life satisfaction. Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics builds on this, defining a “safe and just operating space” bounded by social foundations and ecological ceilings.

On the ground, community-scale initiatives prove the point. Transition Towns, eco-villages, and urban sustainability projects show that social connection, meaningful work, access to nature, and participatory governance matter more for wellbeing than high consumption. Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness framework has improved education, healthcare, and environmental conservation while protecting cultural identity and democracy.

Demographic research backs the approach. Coercive family planning schemes tend to fail, fostering resentment and reducing participation. In contrast, education, healthcare, economic opportunity, and women’s empowerment consistently lower birth rates while boosting wellbeing across multiple dimensions.

Human flourishing within planetary boundaries is possible, and the path that leads to it isn’t through blunt demographic control, but through wellbeing, justice, and regenerative development.

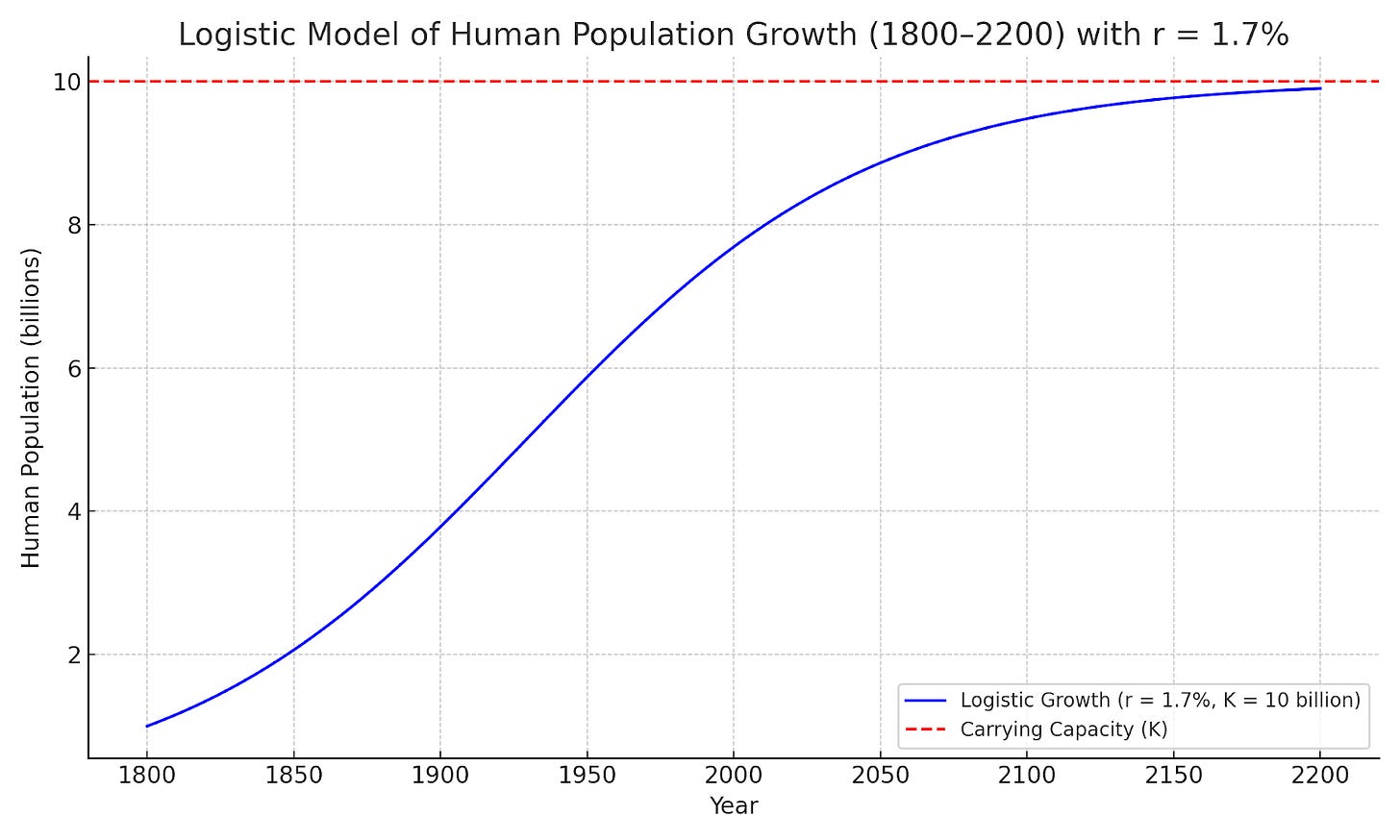

All this is fine, dandy even. But, how should I tackle the human population predicament with the objectivity of a population ecologist? Without any irony, all I have to do is show you this graph.

And then break it down.

This looks like classic exponential growth where numbers increase slowly and then accelerate. Only the time scale is deceptive. What happens is that the exponent of the growth rate changes around about 1950, a change that is hard to see when the data are plotted at this scale. Better to do some maths.

Calculating the exponential growth rate (r) for human population from 10,000 BCE to 1800 CE, requires the formula for exponential growth:

P(t)=P0⋅ert

Where:

P(t) is the population at time t

P0 is the initial population

r is the exponential growth rate

t is the time in years

e is the base of the natural logarithm

The average exponential growth rate of the global human population from 10,000 BCE to 1800 CE was approximately 0.0439% per year—a remarkably slow rate by modern standards. This sluggish growth reflects millennia of constraints imposed by limited food supplies, high disease burdens, and elevated mortality rates, all of which kept population expansion in check. But only to a point.

Agriculture was a net energy source, producing more food than was available to gatherers, so growth to 1800 was still exponential, as a redrawing of the first graph shows. This is the increase that concerned Malthus.

However, if that long-term growth rate had continued beyond 1800, the global population in 2025 would be around 993 million, just under 1 billion people.

This stands in stark contrast to the actual 2025 estimate of 8.1 billion, representing a more than eightfold increase.

The vast divergence highlights the unprecedented acceleration in population growth after 1800, catalysed by industrialisation, medical and public health advances, increased agricultural productivity (notably the Haber-Bosch process), and sharply declining mortality. For context, the average annual population growth rate between 1950 and 2000 was about 1.7% which is nearly 40 times faster than during the entire pre-industrial era.

40 times faster!

So here is the data again, drawn this time on a very different scale. Change in population is now in the billions, and the growth rate is still exponential, but with a much larger exponent.

This transformation underscores how modern population dynamics are historically exceptional, driven by structural changes rather than simply extensions of ancient demographic trends. We got drunk on fossils and converted all that near-free energy into food and more people.

In population ecology terms, we raised the carrying capacity by growing more food and proved that Thomas Malthus was wrong.

Or was he?

Well, his assumptions certainly were. Food production kept pace with population expansion, as the two are inextricably linked in a deterministic dance. As we said, mammals have to eat.

Fossil fuels removed the constraint on food production through the mechanical expansion of arable land, the use of fertilisers to speed up crop and livestock growth and yield, and the development of industrial-scale food systems.

But here is the thing.

No ecologist has seen a population continue to expand exponentially. Soon enough, a resource limit is reached. Crudely, there are two basic options once the resource limit is reached.

One scenario is where scarcity leads to overconsumption, resulting in population collapse. In the other scenario, where scarcity forces competition, resulting in some winners and losers, the population declines, but it can potentially regulate itself at the resource limit. The latter is the one I looked for in the woodlouse and claimed that density-dependent effects on growth and reproduction were enough to regulate populations.

Both scenarios see contraction, but one is more brutal than the other.

Population ecologists describe the controlled contraction with the logistic equation, which describes how a population grows in an environment with limited resources. Unlike exponential growth, which assumes unlimited resources, the logistic model incorporates a carrying capacity, K, which represents the maximum population size that the environment can sustain.

Here’s a breakdown of the formula:

dN/dt = rN(1 - N/K)

Where:

N = population size at time t

dN/dt = rate of change of the population over time

r = intrinsic growth rate (how fast the population grows without constraints)

K = carrying capacity (maximum population the environment can sustain)

The term (1−N/K) slows the growth as the population approaches the carrying capacity. When N is much smaller than K, the population grows almost exponentially. As N approaches K, the growth rate declines, eventually reaching zero when N = K. This S-shaped (sigmoidal) curve reflects how environmental limits constrain real-world population dynamics, making the logistic equation foundational in population ecology and resource management.

Let’s apply this to the human population since 1800, which we know is growing at 1.7% and set K to be 10 billion people.

The curve predicts rapid growth during the 20th and early 21st centuries, which gradually slows as it approaches the theoretical environmental limit. This slowing is happening now. Fertility rates are declining worldwide, and in some countries, their populations are shrinking. Absolute numbers are still increasing at a rate of 8,000 per hour, but there is a slowing of the growth rate.

We should be pleased about this. It suggests that even as we modify K, hoping to increase it with technology and alternative energy sources, there is some regulation in human populations. The demographic transition model might have some legs.

However, the concept of carrying capacity, which underlies both Malthusian and ecological thinking, is fundamentally flawed when applied to human systems because it assumes static relationships in dynamic systems. Human carrying capacity is a function of social organisation, technology, and values that change faster than ecological timescales. Setting it up as a bar to raise and an upper limit of an equation that allows numbers to remain high is a risky distraction.

So here is my contrary premise, as presented by a population ecologist…

The entire population debate, with its Victorian gentleman as a posthumous ball being batted around, and its careful attention to consumption patterns, social justice, and adaptive capacity, serves as an intellectual displacement activity that prevents confronting more fundamental issues about energy and consumption systems.

While we argue about demographics, we avoid discussing the thermodynamic impossibility of current economic models, the inevitability of energy descent, or the psychological drivers of "more making" that transcend population size.

In professional settings, this means scrutinising every population or sustainability argument for its hidden energy assumptions. In civic contexts, it means steering discussion toward the infrastructures and resource flows that actually determine survival, rather than the headcount.

We've become so focused on whether population matters that we've avoided confronting what the numbers tell us about what happens during overshoot. Overshoot isn’t just a matter of headcount; it’s the moment when the rate of entropy production outstrips the system’s capacity to absorb and re-pattern that disorder.

After that, decline becomes the path of least resistance.

And by every measure that matters, we're already there, and what happens is not pretty.

Helpful Sources

Borlaug, N. E. (2000). Ending world hunger. The promise of biotechnology and the threat of antiscience zealotry. Plant Physiology, 124(2), 487-490.

Buch-Hansen, H., & Koch, M. (Eds.). (2021). Degrowth through income and wealth caps? Ecological economics, social equity and the future of capitalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hartmann, B. (2016). Reproductive rights and wrongs: The global politics of population control (3rd ed.). Haymarket Books.

Hickel, J. (2020). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world. Heinemann.

Jackson, T. (2017). Prosperity without growth: Foundations for the economy of tomorrow (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Lee, R. (2003). The demographic transition: Three centuries of fundamental change. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(4), 167-190.

Mazzucato, M. (2021). Mission economy: A moonshot guide to changing capitalism. Harper Business.

Nielsen, K. S., Clayton, S., Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Capstick, S., & Whitmarsh, L. (2021). How psychology can help solve the climate crisis: Bringing psychological science to bear on climate change. American Psychologist, 76(1), 130-144.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Parrique, T. (2022). The political economy of degrowth. Palgrave Macmillan.

Piketty, T. (2020). Capital and ideology. Harvard University Press.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F. S., Lambin, E. F., ... & Foley, J. A. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472-475.

Rosling, H., Rosling, O., & Rosling Rönnlund, A. (2018). Factfulness: Ten reasons we're wrong about the world—and why things are better than you think. Flatiron Books.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

Steffen, W., Rockström, J., Richardson, K., Lenton, T. M., Folke, C., Liverman, D., ... & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2020). The emergence and evolution of Earth System Science. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1(1), 54-63.

Walker, B., & Salt, D. (2012). Resilience thinking: Sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world. Island Press.

Whitmee, S., Haines, A., Beyrer, C., Boltz, F., Capon, A. G., de Souza Dias, B. F., ... & Yach, D. (2021). Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The Lancet, 397(10269), 1973-2028.