Mindful Progress Beats Impossible Perfection

Do we have the courage to choose progress over perfection?

When the good is good enough, it might be better to run with it than wait for the best to appear. When time is short, good can be the only option.

Have you ever noticed how striving for perfection can stop you from taking action?

As an ecological consultant to companies wanting to engage in the carbon markets, I learned this the hard way. I told farmers and project developers what actions would increase carbon in the soil in general, while the carbon registries insisted on knowing the precise gains.

This tension between practical and perfect sits at the heart of our modern environmental challenges.

Whether you're a student grappling with overwhelming ecological data or someone concerned about leaving a better planet for your grandchildren, pursuing perfect solutions often prevents good ones from happening.

Today, I want to share more of a powerful insight that transformed how I approach environmental problems—one that dates back to Voltaire but speaks directly to our current predicament.

Understanding this principle will help you:

Cut through the paralysis of environmental complexity

Make confident decisions with imperfect information

Take meaningful action despite uncertainty

Balance idealism with practical progress

Focus your energy where it matters most

Soil carbon sequestration is a bit technical, but it is a perfect example of how pursuing the "best" solution can sometimes prevent good outcomes.

Don't worry if you're unfamiliar with soil science; this story reveals a universal truth about progressing in complex systems.

It turns out that embracing "good enough" could be our most powerful tool for environmental progress.

Let me show you why.

The best is the enemy of the good

François-Marie Arouet is better known to most of us as the influential Frenchman Voltaire, a prolific writer, historian and philosopher of the Enlightenment who quoted an invaluable Italian proverb over 200 years ago

Le meglio è l'inimico del bene

The best is the enemy of the good

Voltaire was a critic of Christianity and the Roman Catholic Church and advocated for freedom of speech, religion, and separation of church and state. These were risky topics to be contrary about in the 1700s, but then again, it was the Enlightenment.

We can safely assume that Voltaire was especially enamoured with the ‘enemy of the good’ striving for perfection as he also uses the phrase to begin his moral poem La Bégueule

Dans ses écrits, un sage Italien

Dit que le mieux est l'ennemi du bien.

In his writings, a wise Italian

says that the best is the enemy of good

There are uncountable instances throughout history that could lead to such a ‘pursuit of perfection’ aphorism.

The best runner wasn’t the only one to escape the lion. The best clan leader couldn’t gather more resources for his tribe than could be gathered by willing hands.

The best tractor couldn’t plough all the fields. The best story on Medium is not the only one that gets applause.

But why is this formulation of truth so important to mindful sceptics?

After four decades of working among academics, scientists, policymakers and bureaucrats, all with perfectionist tendencies and keen to be the best or at least to scoot across their meritocracy pond as fast as their duck peddling can take them, I might have an answer.

It’s because the best is unattainable, and perfect is the enemy.

Let me explain using one of our favourite topics, soil organic carbon.

The best is the enemy of the good for soil organic carbon

This will get technical, but knowing about this critical mechanism is essential.

If you want to skip ahead to the next section, take with you the idea that soil needs carbon for plants to grow; increasing carbon in soils helps production and can assist with achieving net zero emissions—if we accept good enough and don’t strive for precision.

Here are the details.

Plants grow because they have adequate supplies of nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P) and sulphur (S), access to sunlight, water and somewhere for their roots to hold up the whole mechanism.

Invariably, that support substrate is soil.

Much of the cycling of N, P, S and other plant nutrients in the soil is driven by biogeochemical and biophysical processes involving the soil organic matter (SOM).

The carbon component of SOM, what researchers call soil organic carbon (SOC), is also a sizeable terrestrial carbon pool that constantly exchanges carbon dioxide (CO2) between soil-plant systems and the atmosphere and has a direct impact on the Earth’s carbon budget and CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere.

When carbon is lost from the soil, it ends up in the atmosphere and adds to the warming potential, but soils can also absorb carbon by drawing down CO2 via plants and storing it as SOC.

Any SOC in the soil is the balance of plant-derived C added to the soil as organic residues and carbon losses from SOM, primarily as CO2 respired by the soil organisms.

When the net balance of soil carbon increases over some baseline level, we call this sequestration, an option to help balance our skewed carbon budgets. We need soil to gain soil carbon to help pull carbon from the atmosphere and slow climate change. We also need them to hold onto carbon because then plants grow.

There are three ways that carbon can accumulate in soils…

increasing plant C inputs to soils,

storing a more significant proportion of the plant-derived C in the longer-term C pools in the soil or

by slowing decomposition.

Soil scientists have studied and know the ins and outs of these options in most agricultural production systems worldwide.

Whilst it can be hard to predict specific SOC levels and changes, the generalities are clear—leave more plant biomass to decompose, keep ground cover, add organic inputs, and reduce soil disturbance to see a net SOC gain in most agricultural situations.

We also know some common consequences from increased plant-derived carbon inputs, added recalcitrant carbon pools to soils, or slowed decomposition are that…

the rates of C sequestration are modest, mostly less than 0.5–1 Mg C ha−1 yr−1

C sequestration only happens for a few decades and with decreasing rates of accumulation over time

other greenhouse gases can affect the benefits of SOC accumulation

In other words, it can be hard to demonstrate the net benefit from actions that should increase SOC over a baseline level.

And soil is notoriously fickle medium. Its chemistry and biology vary from field to field, patch to patch and down to the microscopic differences at the scale of fine roots. It is almost impossible—even with modern sensors to measure the variables and computer models to predict what will happen to them—to know precisely the current and future amount of SOC in the three dimensions of soil.

We can predict if soil will accumulate or lose SOC over time, given the soil type, weather, and management practices, but precise amounts of change are hard to determine with any certainty.

However, we do know this.

Returning SOC to degraded soils is a win-win land management option. It mitigates greenhouse gas emissions and helps maintain soil health for consistent plant growth.

What is there not to like?

The scientists who figured out all the details on SOC are spoiling the party. They say there are issues with soil C sequestration as a climate mitigation option… it only lasts a short time, can easily be reversed and might leak.

Leakage happens when activity shifts to somewhere else. Stop ploughing here, but someone else ploughs the same amount of land on their farm. So, a production activity is stopped to increase SOC in one location, which might mean it is released from elsewhere because production was shifted to another place.

For the bean counters, the most worrying factor is that SOC is hard to measure precisely. This becomes a problem if there are volume-based incentives or trading systems for the sequestration.

For example, suppose a farmer changes his production practices by ploughing less and maintaining a cover crop to increase SOC in his degraded soils. It works to increase SOC, and he decides to trade the gains for carbon credits.

He makes a few soil measurements across his 500 ha of fields that grow canola and uses a model to predict the amount sequestered. It comes to 0.95 Mg C ha−1 yr−1 or just shy of 4 tonnes of CO2e per hectare or 2,000 carbon credits per annum across his 500ha.

But what if the sequestration is 0.45 Mg C ha−1 yr−1?

The farmer could be claiming double the actual amount of credits. That is way too much error.

Nothing is perfect

It is not an ideal mechanism, so the scientific advice is to be cautious.

Whilst these issues are real, they should not be showstoppers.

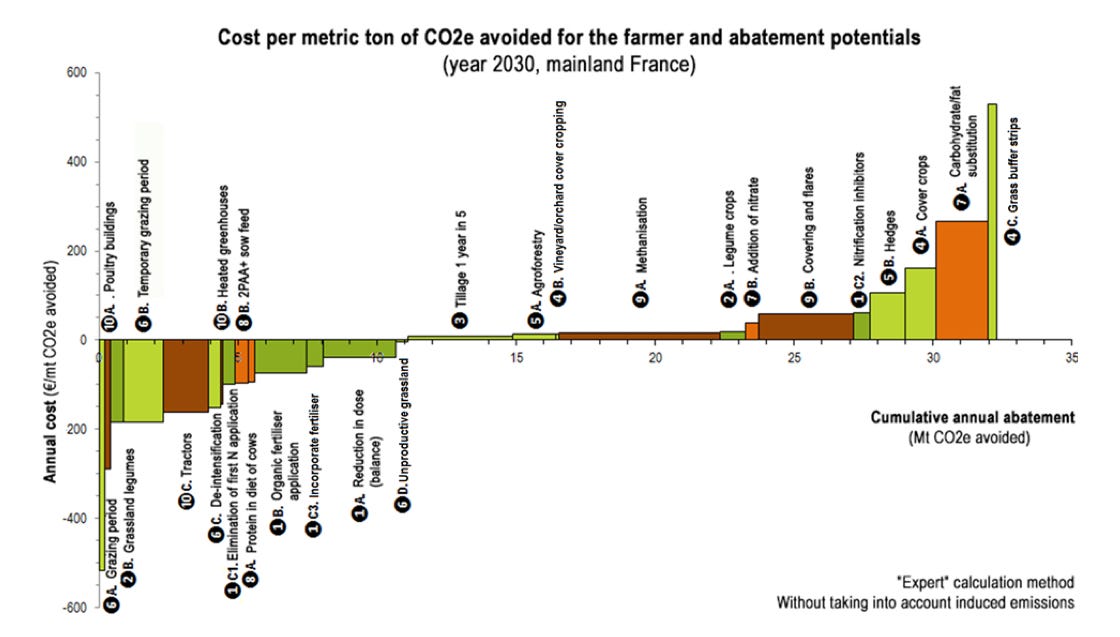

Indeed, increasing SOC levels through changes to agricultural management practices can be a relatively low-cost way of reducing emissions. Plenty of the actions on the left of this marginal abatement cost curve show that the cost per tonne of CO2e is avoided for the farmer and that the abatement potential for France is negative, which means that the farmer makes money from them.

There are also plenty of actions that can be beneficial. There is no need to prescribe just one or two. Farmers can choose among several according to their circumstances.

SOC sequestration could even be a policy priority, perhaps with an incentive for the practices on the left of the graph—especially grazing and fertiliser management.

Only nervous Nelly scientists are providing the excuse for politicians to dither. What if a payment scheme incentivises the wrong farmers to participate in schemes, such as those that do not offer the best sequestration potentials? Goodness, this is not even science but a compliance issue.

Then, they conclude that however significant the overall global potential for carbon sequestration in soil is, current barriers suggest that the actual achievable contribution is constrained.

Of course, it is… the best is always unattainable.

However, rather than perfectionism, the good is good enough when the sequestration win is also a production and resilience win.

Being a mindful sceptic about embracing progress

I don’t often do this, but here is a quote from George Monbiot, a British writer and environmentalist known for his political activism who, I’m guessing, would identify with Voltaire.

Hypocrisy is the gap between your aspirations and your actions. Greens have high aspirations — they want to live more ethically — and they will always fall short. But the alternative to hypocrisy isn’t moral purity (no one manages that), but cynicism. Give me hypocrisy any day…

George Monbiot

After four decades in ecology, I've learned that perfect solutions rarely happen in complex systems. Nature herself doesn't deal in perfection but always gets the job done.

Think about this.

Every hour, the equivalent of a small town joins our global population. They all need food, energy, and resources. Meanwhile, we're caught in an impossible bind of burning fossil fuels to meet immediate needs while knowing this threatens our future. It's easy to feel paralysed by the enormity of this challenge.

Global energy demand and clearing land for agriculture to maintain food supplies is a tide of emissions that is hard to stop. We need every climate mitigation option available.

If there is an option that removes carbon from tha atmosphere—as opposed to just an emission reduction—that also helps to grow more food consistently, only a crazy person can ignore it.

Building carbon in soil can tackle multiple problems at once.

It might not be perfect. The measurements might not be precise. The results might vary. But it works.

In academia, we often get stuck seeking perfect data while farmers already implement "good enough" solutions to improve their soils. Both approaches have value, but waiting for perfection usually means missing opportunities for real progress.

This is where George Monbiot's insight is profound, especially for environmental actions. We're all hypocrites to some degree when it comes to environmental issues. We want to live perfectly sustainable lives but fall short in countless small ways.

But that gap between aspiration and action isn't a failure. It's the space where real change happens.

Every time we choose good enough over perfect inaction, we're moving forward. Every imperfect solution implemented is better than a perfect one forever stuck in planning.

So what does this mean for you?

Start small.

Observe the soil beneath your feet. Question claims, but don't let scepticism paralyse you.

Embrace solutions that work, even if they're not perfect. Because in the end, good enough actions today will achieve far more than perfect solutions tomorrow.

Remember, being a mindful sceptic isn't about having all the answers.

It's about staying curious, thinking critically, and being willing to act with the best information we have right now. Because sometimes, good enough is good enough.

What small, imperfect action will you take today?

Mindful Momentum

Stop for just one minute next time you walk on grass or soil.

Look closely at the ground. Is it bare or covered with plants? Hard or soft? What colour is it? Just notice, without judgment.

Do this for a week and jot down what you see.

You'll start understanding soil as a living thing, not just dirt, which is the first step in grasping why "good enough" soil management matters.

Key Points

The concept "the best is the enemy of the good" illustrates how perfectionism can hinder environmental progress, with soil carbon management providing a clear example of where reasonable solutions are often delayed while waiting for perfect ones. This tension between ideal and practical approaches affects how we tackle urgent ecological challenges.

Soil organic carbon plays a vital role in agricultural productivity and climate change mitigation. While the science shows that increasing soil carbon has multiple benefits, concerns about measurement precision and verification often prevent the implementation of known beneficial practices, demonstrating how the pursuit of perfect data can block practical progress.

A mindful sceptic recognises that while scientific precision is necessary, waiting for perfect solutions in complex systems like soil carbon sequestration can delay meaningful action. Evidence suggests that many current "good enough" soil management practices can improve both food production and carbon storage, even if their exact impacts cannot be perfectly quantified.

This case study of soil carbon illustrates a broader principle for environmental action that implementing imperfect but beneficial solutions often achieves more than waiting for perfect ones. This approach exemplifies mindful scepticism by balancing the need for scientific rigour with pragmatic action in the face of urgent environmental challenges.

Curiosity Corner

This issue of the newsletter is all about…

Through the lens of soil carbon sequestration, we explore how pursuing perfect solutions often prevents good ones from happening, revealing why mindful sceptics must balance scientific ideals with practical progress to tackle urgent environmental challenges.

Here are 5 better questions from this issue, each pushing our thinking beyond surface-level reactions…

1. Instead of asking 'How can we perfectly measure soil carbon?', what if we asked 'What carbon-building practices are farmers already using successfully?' This reframe shifts us from theoretical perfection to practical wisdom, acknowledging that solutions might already exist in unexpected places.

2. Rather than 'Why isn't our climate action perfect?', shouldn't we be asking 'What good-enough steps could we implement today?' This gets to the heart of action over analysis, pushing us past the paralysis of seeking flawless solutions. I've seen too many promising projects stall while waiting for perfect conditions.

3. Instead of 'How do we get everyone to adopt the best practices?', what about 'What makes some farmers willing to try imperfect solutions?' From my years working with farmers, I've learned that understanding motivation often matters more than perfect methodology. This question explores the human side of environmental action.

4. Rather than asking, 'What's the ideal carbon level?', shouldn't we ask, 'What's the minimum improvement that would make a meaningful difference?' This shifts our thinking from abstract ideals to practical thresholds - something I wish I'd understood earlier in my research career.

5. Instead of 'How do we eliminate uncertainty in measurement?', what if we asked, 'How much certainty is good enough to act?' This question challenges our academic instinct for perfect data, pushing us to consider when we know enough to move forward.

What question would you add to this list?

In the next issue

Ever watched a politician confidently declare something you know is scientifically impossible?

In our next issue, we'll unpack the art of political deception and what it means for evidence-based decision-making. Drawing from real examples in environmental policy, I'll show you how mindful scepticism can transform frustration into focused action.

Join me for an honest conversation about truth, lies, and finding balance in a post-truth world.