Fish On Friday

A sceptical guide to aquaculture marketing and reality

Demand and the nutritional benefits of fish have produced a phenomenal rise in aquaculture. Is fish farming the answer to sustainable seafood?

I am one lucky dude. I was born into a Western culture at a time of crazy abundance. I had access to a remarkable education and leveraged it into a science career that kept me busy, entertained and fulfilled.

I have a loving family, a warm home and a set of golf clubs.

Recently, I also became the owner of a caravan.

The fallout from the COVID-19 travel restrictions brought on this unexpected development. Instead of travelling overseas in retirement, which would have been more outrageous fortune, I now travel locally, mainly to the east coast, which in Australia is spectacular.

It tends to look like this…

Or sometimes this…

On our travels, my wife and I seek out the best vanilla slice, currently held by an excellent patisserie in Megalong, Kangaroo Valley. We also try to source the best fish and chips. This is a bit trickier for the purveyors, given that the fish is usually fresh out of the ocean, so what they do to cook it matters.

We have two joint favourites: Bub’s Famous Fish & Chips, Nelson Bay Marina, and the Husky Fresh Fish & Chip Co, Huskisson. Both know how to grill, and the latter makes the best crumbed batter ever.

Every time, I bless my good fortune to eat such a magnificent lunch and ponder the miracle of nature that the ocean still has any fish left to catch.

Because humans like seafood.

Fish are perfect parcels of nutrient-dense food, and humans have a long relationship with fish as a food source and with the habitats where fish live.

We have always been keen on a seafood platter and have risked life and limb to secure fish supplies. Working on a trawler at night on an angry sea takes real courage.

In this week’s Mindful Sceptic, we will have a look at fish, specifically aquaculture, which is the main reason there are still fish in supermarkets.

Fish on Friday

Christians are supposed to fast on the sixth day of the week, a Friday.

Back in the day, fish was the food of the poor, so on the sixth day, the wealthy would fool themselves that they were roughing it and meet the requirement to fast by eating fish on Friday.

Fish and chips on Friday is still a thing in Britain, although in 1985, the Catholic Church in England and Wales allowed Catholics to substitute another form of penance instead of fasting or fish. Maybe they did without ice cream for dessert.

Fish provides excellent nutrition. It is low in fat and a high-quality protein filled with omega-3 fatty acids and vitamins such as D and B2 (riboflavin). Fish is also rich in calcium and phosphorus and is an excellent source of minerals such as iron, zinc, iodine, magnesium, and potassium—no wonder the poor survived on it.

Not strictly fasting then, but hey.

When I was born in 1961, the global average fish consumption in the UK was 19.8 kg per person per year, while the average global John Doe ate 12.7 kg in the year.

By 2017, the UK was still tucking into fish and chips, but at a similar rate to when I was a kid (roughly 19.7 kg per person per year). Meanwhile, the global John munched almost double at 21.4 kg per year.

On Friday, the rich kept to their fish, and the poor, half the global population live on less than $10 a day, ate a lot more.

There has also been a change in where the fish is sourced.

In 1961, the total fish eaten was roughly 36 million tons, and 94% were wild-caught. The oceans, lakes and rivers coughed up the catch.

In 2015, it was 200 million tons.

However, once extraction was roughly 90 million tons, the oceans and lakes were at their limit, and the rest had to come from somewhere else. Humans began to farm fish at scale. There was an exponential increase in aquaculture, rearing aquatic animals or cultivating aquatic plants for food.

Since 2012, humans have grown over half the tonnage of fish consumed.

Aquaculture became popular as the wild catch declined, especially since that catch plateaued in the 1990s. The demand for fish was rising, but despite the technology and vast fishing fleets, the wild-caught supply needed help to keep up.

Businesses saw the opportunity and met the need through various forms of aquaculture.

Marine (Mariculture)

Fish farming in ocean pens or cages (e.g. salmon, tuna)

Seaweed farming (e.g. kelp, nori)

Shellfish farming (e.g. oysters, mussels, clams)

Open ocean aquaculture (offshore cages in deeper water)

Freshwater Aquaculture

Pond culture (e.g. tilapia, carp, catfish)

Raceway systems (flow-through tanks in streams or canals)

Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS – closed-loop, land-based systems)

Brackish Water Aquaculture

Estuarine shrimp farming

Milkfish and mud crab cultivation in coastal ponds

The rise in seafood production from aquaculture is remarkable.

Aquaculture is important, but not without issues

There is plenty to like about aquaculture: fish year-round for consumers, incomes for producers, and reduced pressure on wild fish stocks are all good.

Aquaculture can also provide ecosystem services through wastewater treatment, bioremediation, habitat structure, and the rebuilding of depleted wild populations through stock enhancement and sprat dispersal.

Farmed fish and shellfish species are cold-blooded and physically supported by water. They are more efficient feed converters and have higher edible yields than most terrestrial animals.

But they are still consumers; they have to be fed.

As of 2022, over two-thirds of global aquaculture production relied on supplemental feed inputs, primarily sourced from human-inedible by-products of crop, livestock, and fisheries sectors, including fishmeal and fish oil derived from wild-caught fish.

Aquaculture's dependence on supplemental feeds has been a longstanding characteristic of the industry. They typically comprise fishmeal and fish oil, traditionally produced from wild-caught forage fish. However, this practice has raised sustainability concerns due to its pressure on wild fish populations. The industry has increasingly turned to by-products from crop and livestock processing, as well as trimmings from fish processing.

In Australia, for example, the aquaculture sector has significantly reduced its reliance on traditional fishmeal. Less than 15% of aquaculture feed in the country now contains fishmeal, with under 10% sourced from wild fish. Instead, feed producers are increasingly utilising poultry by-products and fish processing trimmings.

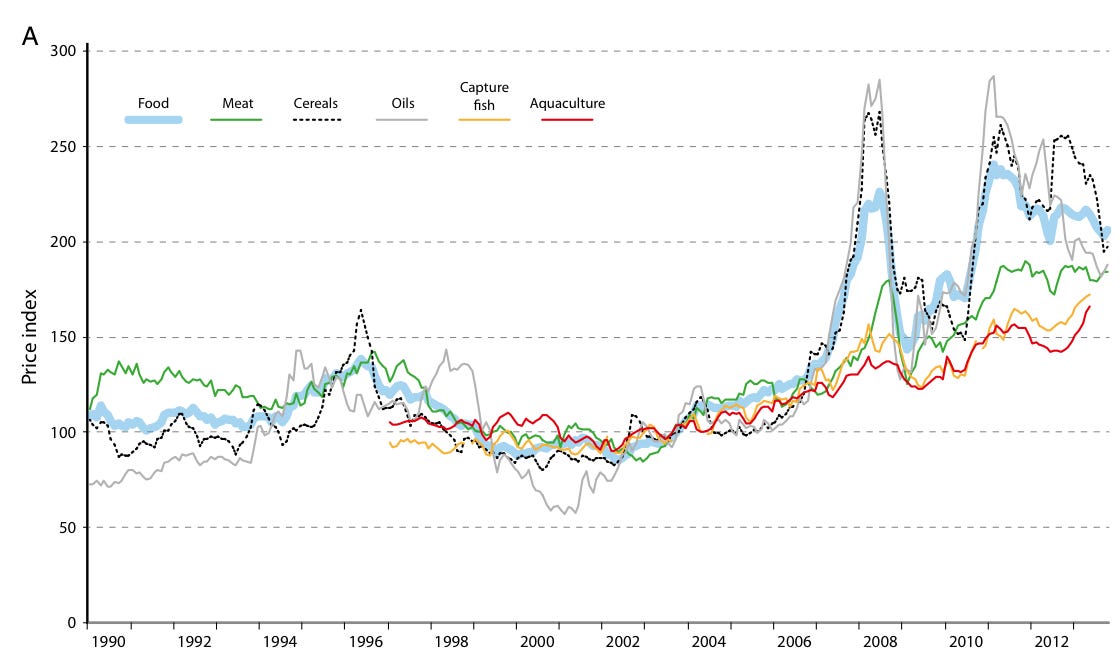

Aquaculture is a production process similar to farming with inputs of labour, energy and nutrients. Fish from the pens and ponds come at a cost. However, the price of farmed fish is relatively stable globally compared to other food types, especially cereals and oils. This is a good thing, significantly, because price spikes in wheat, rice and corn harm the poor.

Aquaculture has buffered the global demand for fish from the plateau in production from capture fisheries. We now farm a lot of fish because far fewer fish are left in the seas, oceans, and lakes.

But it is not all fish and chips on Friday.

Aquaculture is not a panacea

Aquaculture comes with most of the general problems and consequences of agricultural intensification, including energy, nutrient and pesticide inputs, mechanisation, sustainability, as well as a few of its own…

Pollution, especially nitrate leaks

Coastal habitat loss

Potential disease and parasite transmission between farmed and wild fish populations, introduction and spread of invasive species

Appropriation of freshwater resources

Depletion of wild fish populations to stock aquaculture operations

Overfishing of wild fish populations used as ingredients in aquaculture feeds

The use of wild fish in aquafeeds can also have food security implications for low-income households, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia and Latin America, that depend on low-trophic-level fish as a critical constituent of their diets.

In short, aquaculture is an input-output system like intensive farming on land.

Intensification transforms food production into an industrial process, prioritising efficiency and profit but relying heavily on external inputs of energy and nutrients; inputs that must be sourced from elsewhere.

Unlike wild-caught fish that are simply harvested, farmed fish require ongoing feeding, care, and environmental management to grow. This shift underscores the hidden dependencies that underpin modern aquaculture systems.

And like many industrial processes on land, there is waste.

Some of these are obvious and direct pollution events, like the leaks of nitrate from fish pens, but there are other externalities (consequences of production that appear outside of the supply chain) such as the loss of habitat and depletion of wild fish populations.

The bottom line of aquaculture

Aquaculture is essential to the 22 trillion kilocalories daily to feed everyone well.

Wild-caught fish cannot feed the 8 billion people we already have, plus the extra 8,000 an hour from the population spike. Aquaculture is essential to meet the shortfall in demand.

But that demand is enormous.

If the 8,000 new arrivals in the last hour ate the average amount of fish per person per year (21 kg), then we need an additional 168 tonnes of fish per annum for each hour of every day, 24/7.

Humans are designed for hunting, gathering, and digesting various food types, from prawns to papaya. This omnivory has contributed to our widespread success. It also gives us flexibility and adaptability.

Humans are also large mammals with an evolved physiology designed to process nutrient and energy-dense food.

Elephants are big mammals too. They use their size to forage widely and consume vast amounts of relatively nutrient-poor foods, primarily grasses, leaves and even bark at a push—they have a high throughput strategy, meaning they are eating most of their waking hours.

Humans went the other way.

We take infrequent meals and hold onto our food to digest it thoroughly. We could only be successful in this strategy with foods high in nutrients and energy. Feeding everyone well means supplying at least some of those high-density nutrient meals.

Throughout recorded and prehistoric history, humans have found fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants in rivers, lakes, and the ocean to make good meals. We will always be keen on Friday’s fish.

So what does a mindful sceptic make of all this?

Beyond Simple Answers

Despite the rhetoric, fish farming is inherently evil. It's just that farming fish can quickly go the way of industrial agriculture on land. It becomes over-reliant on inputs, especially energy, while systematically avoiding responsibility for its externalities.

This pattern should sound familiar.

We've seen it with intensive agriculture, factory farming, and even renewable energy projects that promise sustainability while quietly shifting environmental costs elsewhere.

Aquaculture can follow the same playbook to meet immediate demand while externalising long-term consequences.

Then there is this uncomfortable reality…

Neither aquaculture nor our current wild fish catch is truly sustainable. Both systems operate beyond planetary boundaries, just through different mechanisms. Wild fishing directly depletes ocean ecosystems; aquaculture does it indirectly through feed requirements and waste streams.

We've simply traded one form of unsustainability for another.

A mindful sceptic recognises that this reality doesn't mean abandoning seafood or aquaculture entirely. Instead, it means asking better questions.

When evaluating any aquaculture operation, apply this sceptical lens…

Follow the inputs | Where do the feed, energy, and materials come from?

Track the outputs | What happens to waste, both direct and indirect?

Question the metrics | Who defines "sustainable" and what are they measuring?

Consider the alternatives | What would happen without this intervention?

Admiring those beautiful Australian coastlines, enjoying my fish and chips, I'm struck with guilt over my good fortune. The very abundance that allows me this pleasure depends on systems that my consumption undermines.

I could slip easily into despair. Even if I sold the caravan and lived on kale for the rest of my days, someone else would be in the van. People are like that.

So here is an alternative.

The mindful sceptic's approach isn't to reject aquaculture wholesale, but to demand better. Some fish farming operations innovate with closed-loop systems, alternative feeds, and genuine ecological integration. Let’s find, evaluate and promote those that work.

Next time you're offered that Friday fish special, pause for just a moment. Not to feel guilty, but to exercise your sceptical muscles. What questions would you ask about this fish's journey to your plate? What evidence would convince you it was produced responsibly?

Fish and chips, anyone?

Absolutely, just order with our eyes wide open.

Mindful Momentum

The Seafood Detective Challenge

Next time you're shopping for fish, become a mindful investigator.

Choose three seafood products and examine their labels and marketing claims for five minutes. What specific information is provided? What's conspicuously absent?

Notice the language used… "sustainably sourced," "responsibly farmed," "ocean-friendly", and ask what evidence I would need to verify these claims?

This isn't about becoming a food purist; it's about exercising your sceptical muscles in a low-stakes environment. You might discover that "wild-caught" doesn't automatically mean sustainable, or that some aquaculture operations provide remarkably transparent information while others rely on vague feel-good phrases.

The goal is to develop your ability to distinguish between substantive information and marketing spin, a skill that applies far beyond the seafood counter.

Key Points

Wild-caught fish consumption plateaued in the 1990s at approximately 90 million tonnes annually, unable to meet rising demand from a growing global population that now consumes over 200 million tonnes of seafood yearly. This gap has been filled by aquaculture, which since 2012 has provided more than half of all fish consumed globally. The shift represents one of the most significant changes in human food production systems, moving from purely extractive harvesting to managed cultivation of aquatic species.

Fish farming provides year-round protein supplies, supports rural economies, and reduces pressure on wild fish stocks while delivering more efficient feed conversion than terrestrial livestock. However, the industry increasingly relies on external inputs, including fishmeal, fish oil, and energy-intensive infrastructure. This dependency creates vulnerability to supply chain disruptions and raises questions about the net environmental benefit when feed ingredients are sourced from wild-caught fish or agricultural by-products.

While industry advocates emphasise reduced land use and efficient protein conversion, critical analysis reveals significant environmental costs, including nutrient pollution, habitat modification, and potential disease transmission to wild populations. Modern aquaculture operations function as industrial systems that externalise waste streams and resource consumption, following patterns established by intensive land-based agriculture rather than representing a fundamentally different approach to food production.

Rather than categorising fish farming as inherently sustainable or unsustainable, informed consumers and policymakers benefit from examining specific operations through multiple lenses: input sources, waste management practices, local ecological impacts, and social equity considerations. This approach recognises that some aquaculture innovations genuinely advance sustainability goals. In contrast, others simply rebrand industrial practices with environmental marketing language, requiring ongoing critical assessment rather than blanket acceptance or rejection.

Curiosity Corner

This issue of the newsletter is all about…

While aquaculture promises sustainable seafood, applying critical thinking reveals that both wild-caught and farmed fish operate beyond planetary boundaries, just through different mechanisms.

5 Better Questions from this issue of the newsletter…

Who compiled the global seafood production statistics we rely on, and what data gaps might exist in regions with limited monitoring infrastructure?

This question is better because it challenges us to examine the foundation of our understanding rather than simply accepting impressive-sounding numbers, helping us develop habits of source verification that apply across all environmental claims.

When aquaculture operations claim to use "sustainable" feed sources, what specific metrics define sustainability and who established those standards?

This cuts through marketing language to reveal the human decisions and potential conflicts of interest behind environmental certifications, building skills to decode greenwashing across industries.

How do the total system costs of aquaculture compare to wild-caught fishing when we include externalities like feed production, waste treatment, and ecosystem disruption?

This question is superior because it demands systems thinking rather than narrow comparisons, training us to recognise hidden costs that often determine true sustainability.

What economic and social pressures drive the rapid expansion of industrial aquaculture, and how do these forces shape environmental outcomes?

This moves beyond technical considerations to examine the underlying drivers of environmental problems, developing our capacity to understand root causes rather than just symptoms.

Which aquaculture innovations show genuine promise for reducing environmental impact, and what evidence standards should we apply to evaluate their claims?

This question is better because it maintains pragmatic optimism while demanding rigorous evaluation, embodying the mindful sceptic's balance between cynicism and gullibility.

In the next newsletter issue

We’re told the future is electric.

Electric vehicles will solve the climate crisis without disrupting our lifestyle. You can keep your car, your speed, and your convenience by simply swapping out the fuel. But what if the plug that powers your Tesla draws from the same grid that burns coal by the trainload?

In the next issue of Mindful Sceptic, we take a hard look at the upstream realities of electric cars and the downstream comfort they offer. We'll follow the wires back to their source, trace the emissions through the illusion, and ask why technologies that promise change without sacrifice are so politically seductive and so ecologically misleading.

If you think EVs are the answer, you may want to read the fine print.

Science Source

Troell, M., Naylor, R. L., Metian, M., Beveridge, M., Tyedmers, P. H., Folke, C., ... & De Zeeuw, A. (2014). Does aquaculture add resilience to the global food system? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(37), 13257-13263.

Very interesting article. I believe tuna farming involves catching small tuna for raising in pens, so it is actually a form of wildcatch as well as a form of mariculture.