Coal-fired Teslas

Electric cars and the uncomfortable truth about technologies that promise change without sacrifice

Electric cars are touted as the transport solution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and saving the planet from excessive warming. If only it were so simple…

This week, we have a slightly different newsletter. It is shorter, maybe not sweeter, but most likely an eye-opener. It is also a classic application of mindful scepticism.

It's about cars, specifically electric ones. And it’s a metaphor for a challenge at the heart of every application of mindful scepticism to the human predicament. But we will get to that.

In the spirit of short(er), let’s go.

But first…

The perfect EV

If you drive a Tesla Model S for 100 miles, it will use 34 kWh of electricity, more or less. In petrol terms, that is about 100 MPG and sounds like a win for the driver.

If electricity costs an average of $0.17/kWh, the yearly cost to drive a Tesla Model S 15,000 miles is $867.

For the same mileage (15,000 miles), a petrol car equivalent to a Tesla Model S would likely cost around $1,846.40 in fuel in the US, assuming an average consumption of 26 MPG and a gasoline price of $3.20 per gallon.

Clearly, the Tesla is much cheaper than a gas guzzler.

Driving those 15,000 miles of silent motoring pleasure needs roughly 5,000 kWh.

But what about the carbon emissions?

The U.S. EPA states that burning one gallon of gasoline produces about 9 kg of CO2, a widely accepted figure for tailpipe emissions. Given the expected MPG and the 15,000 miles travelled, a new petrol car would be expected to release a little over 5 metric tons of CO2.

Surely an electric car would have fewer emissions.

Electric engines are more energy efficient and better for the atmosphere than internal combustion engines. Using electricity to drive the car means no exhaust and no nasty fumes. Aside from the embodied energy in the materials that make up the vehicle, the carbon footprint should be minuscule.

Perhaps.

The thing is, it depends on where the electricity comes from.

When the first Tesla was sold to Elon Musk in 2008, just shy of 50% of the electricity in the U.S. came from coal-fired power stations. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the electric power sector accounted for over 90% of U.S. coal consumption.

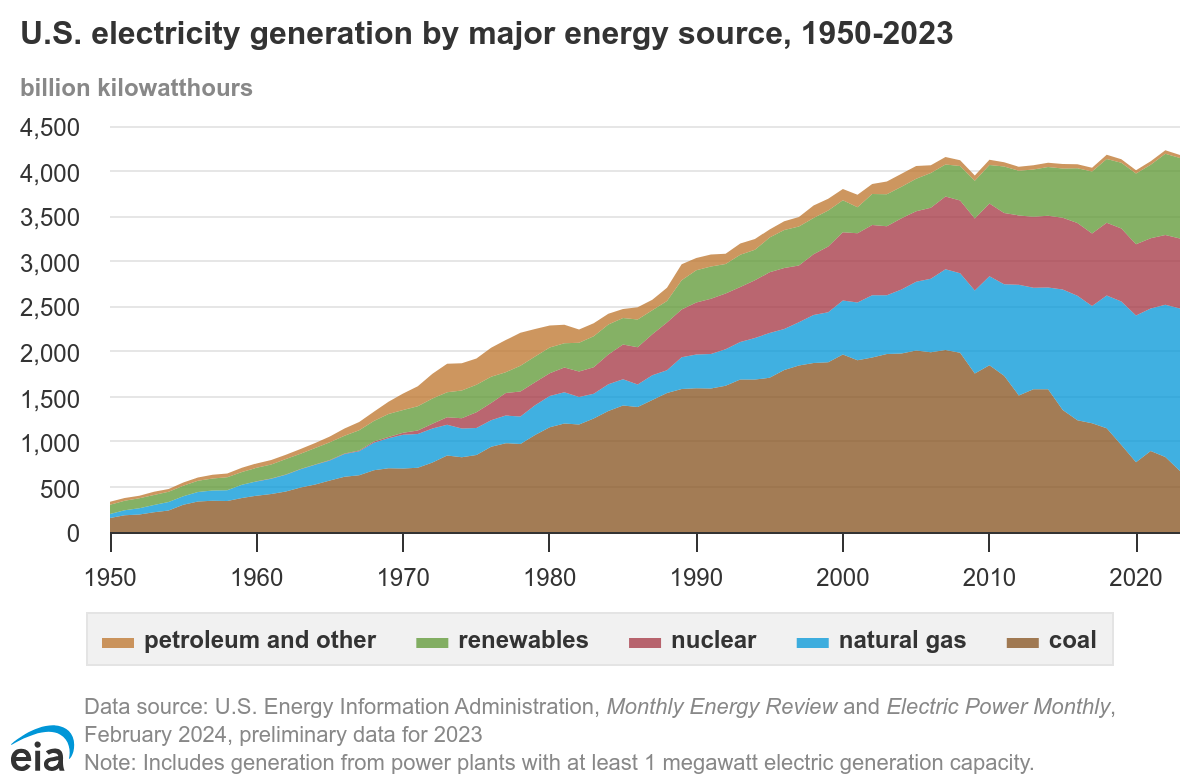

Here are the trends in electricity generation by fuel source in the US from 1950 to the present, according to the US Energy Information Administration. In 2008, coal generated just under 2 billion kw/h.

Back to the emissions from the Tesla.

It takes about one pound of coal (0.45 kg) to generate one kilowatt hour (kwh) of electricity. So each Tesla needs 2,250 kg of coal to produce the electricity for its yearly travel.

Turns out that coal has a carbon intensity of about 1,000g CO2/kWh, oil is 800g CO2/kWh, natural gas is around 500g CO2/kWh, while nuclear, hydro, wind and solar are all less than 50 g CO2/kWh.

So here is the thing.

If the Tesla were powered by the coal-fired power station down the road, the 5,000 kWh of electricity generated from 2 metric tonnes of coal to power the Tesla for 15,000 miles would release around 5 metric tons of CO2, a rounding error from the petrol model.

Luckily, only 50% of the electricity came from coal in 2008. So the Tesla emitted half the emissions of the Beemer, assuming all the rest of the electricity was green. Well, not quite.

In 2008, roughly 20% of electricity generation came from gas. Admittedly, this source has half the carbon intensity of coal, but if we added it to the 50% from coal we should add another 0.5 metric tons of CO2 to take the Tesla to 3 metric tons of CO2, 40% less than the petrol car.

But, you will say, it has to be better now with all the renewables we have added since 2008. Well, let’s go back to the graph and do the same calculation for 2023.

The petrol car produces the same amount of CO2 emissions at 5 metric tons.

Coal has declined to 16% of the electricity energy mix, so the Tesla releases 0.8 tCO2 from coal. However, gas has increased to 43% of the mix, so we have to add another ton for a total of 1.8 tCO2, now 64% less than the petrol car.

Now we are getting somewhere.

Calculating this proportion using average emission factors gives a similar result. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) states that in 2023, the U.S. net electricity generation resulted in approximately 367 grams of CO2 per kWh. As before, the U.S. EPA states that burning one gallon of gasoline produces about 9 kg of CO2, the widely accepted figure for tailpipe emissions.

Tesla Model S (Electric) emits approximately 1.94 metric tons of CO2

An Equivalent Petrol Car emits approximately 5.13 metric tons of CO2

Even considering the current US electricity grid mix (which still includes a significant portion of fossil fuels), an electric vehicle generally produces significantly lower operational carbon emissions than a gasoline-powered car for the same mileage.

Note that this calculation focuses on "tailpipe" equivalent emissions. It does not include "upstream" emissions from manufacturing the vehicles, batteries, or the infrastructure, which are more complex to quantify but are typically higher for EVs initially, though they are usually offset over the vehicle's lifespan by lower operational emissions.

What This Teaches Us

This Tesla example gives us three essential mindful scepticism skills that apply far beyond electric cars.

1. Question the invisible infrastructure

We see the sleek Tesla, not the coal plant. We notice the solar panel, not the lithium mine. A mindful sceptic always asks… "What's happening upstream that I can't see?" and ‘What might happen after the fact?” This systems thinking transforms how we evaluate any "green" technology.

2. Timing matters more than we admit.

Electric cars aren't inherently good or bad, their impact depends entirely on when and where we use them. The same technology can be revolutionary in Norway (95% renewable electricity) or counterproductive in Poland (70% coal). Context defeats ideology every time.

3. Beware solutions that feel too comfortable.

The most seductive environmental solutions are those requiring no sacrifice from us. When a green technology promises all the benefits with none of the trade-offs, that's precisely when our sceptical radar should activate.

Next time you encounter any environmental claim, spend thirty seconds asking: "What can't I see? What's the timing? Why does this feel so easy?" Those questions alone will make you a more discerning consumer of environmental information than 90% of people sharing articles on social media.

What should the mindful sceptic do?

Should I rush out and buy an EV when my current vehicle dies?

If you are concerned about emissions, consider buying a second-hand petrol car until they're no longer available. By the time the stock of petrol vehicles is used up, electricity from renewables would give electric cars the emissions profile we think they currently have.

Again, if emissions are a concern, encourage the divestment from fossil fuels, especially coal, but remember that people need electricity for health and well-being. Not everyone can afford to pay heavily for it, especially in developing economies where the alternatives to electricity are charcoal, wood, and cattle dung.

Imagine the environmental cost of a billion more people shifting from electricity to charcoal.

The 2,450 coal-fired power stations globally should become stranded assets, but only when there is enough generation capacity in alternatives.

This last statement hits at the metaphor I mentioned at the start.

The Deeper Pattern

Here's the uncomfortable truth this Tesla example reveals. We are addicted to "more" solutions when the planet needs "less" ones.

Electric cars let us feel virtuous while driving the same distances. Solar panels let us use the same amount of electricity. Plant-based meat allows us to consume the same amount of protein. Green hydrogen promises endless clean energy for endless growth.

Notice the pattern?

Every "green" solution preserves our lifestyle while shifting the problem elsewhere—coal plants instead of exhaust pipes, lithium mines instead of oil wells, industrial agriculture instead of factory farms.

This is where mindful scepticism becomes essential. Our awareness catches us reaching for the comfortable solutions that require no sacrifice, no behaviour change, no difficult conversations about less.

A better question is "What if the problem isn't how we power our consumption, but how much we consume?"

The hardest questions are cultural. Not "How do we make cars cleaner?" but "Do we need this many cars?" Not "How do we power growth sustainably?" but "What if sustainable means smaller?"

The real challenge of mindful scepticism is having the courage to question not just the solutions, but the assumptions that make us need those solutions in the first place.

Most days, we'll choose the Tesla over the bus pass. But the mindful sceptic at least knows what choice they're making.

Mindful Momentum

The Mindful Sceptic's homework

Next time someone proposes a 'green' solution, ask yourself this question…

Does this let me consume the same amount, just differently?

If yes, what more challenging questions am I avoiding?

Key Points

While a Tesla Model S produces significantly lower emissions today (1.94 metric tons CO₂) compared to equivalent petrol cars (5.13 metric tons), this advantage emerged gradually as electricity generation shifted from coal dominance. In 2008, when EVs first gained popularity, coal generated 50% of US electricity, making electric cars only marginally better than conventional vehicles. By 2023, coal's share dropped to 16%, while natural gas increased to 43%, creating the substantial emissions advantage we now associate with electric vehicles. This progression demonstrates how technological solutions can appear ineffective initially but become transformative as supporting infrastructure evolves.

The sleek Tesla represents a broader pattern where consumers focus on immediate, visible technology while remaining unaware of complex supply chains and energy infrastructure. This systems thinking approach applies beyond transportation to all environmental technologies, from solar panels requiring lithium mining to biofuels competing with food crops. Effective critical thinking demands asking "What's happening upstream that I can't see?" and "What might happen after the fact?" These questions transform how we evaluate any purportedly green technology by revealing hidden trade-offs and dependencies.

Electric vehicles exemplify this pattern by allowing people to drive the same distances while feeling virtuous about their choices. Similarly, solar panels enable continued electricity consumption, plant-based meats maintain protein consumption levels, and green hydrogen promises endless clean energy for unlimited growth. This comfortable approach to environmental challenges avoids difficult conversations about reducing consumption, instead relocating environmental impacts from exhaust pipes to coal plants, from oil wells to lithium mines, from factory farms to industrial agriculture.

Mindful scepticism's most valuable application lies in recognising when solutions feel too comfortable and promise environmental benefits without requiring behavioural change or sacrifice. The most productive questions shift from technical optimisation ("How do we make cars cleaner?") to cultural examination ("Do we need this many cars?"). This approach requires courage to challenge not just proposed solutions but the underlying assumptions that create demand for those solutions, ultimately distinguishing between technological fixes that preserve existing systems and genuine sustainability that may require different ways of living.

In the next Issue

We imagine collapse as a loud, catastrophic, unmistakable moment. But what if it's already here, unfolding slowly beneath the noise of normal life?

In the next issue of Mindful Sceptic, we explore how humanity has entered ecological overshoot, consuming 1.7 Earths while pretending we still live within one.

The rules of population ecology haven’t been suspended for us even if we have delayed the consequences with a fossil fuel cheat code. And now that code is expiring. What happens when 8 billion humans discover that nature still keeps receipts?

...be a mindful sceptic.

How does this work if the car considered is a hybrid like a Prius?