Beyond Environmental Targets

Why a mindful sceptic focuses on process

A mindful sceptic will always question conventional wisdom and seek evidence-based solutions. But when it comes to environmental action, we face a paradox: the more targets we set, the less progress we seem to make. Why?

The answer is understanding a fundamental misconception about how change happens in nature and human systems. While our analytical minds crave the certainty of specific targets like ‘plant a billion trees’ or ‘zero emissions by 2050’, our mindful awareness tells us something different—real change comes from understanding and improving processes, not just chasing numbers.

In this week's issue of Mindful Sceptic, we'll explore a radical yet pragmatic approach to environmental action that aligns with scientific understanding and mindful scepticism.

We'll use ecological thinking to challenge conventional wisdom and discover how shifting focus from targets to processes can lead to more meaningful, lasting change.

The Challenge of Making a Difference

Do you feel like you make a difference? Sometimes, it is hard to know for sure.

As a kid, I was always told that being a good person is the best thing in life. Be kind, help others and do no harm. My religious parents preached all about improving the world through good deeds.

It turns out that is what self-help manuals and gurus from all corners tell us—every small act of kindness contributes. Even in an uncertain world, every little bit helps. Meanwhile, humanity creates an endless supply of trauma in need of a salve.

As this newsletter describes in often disturbing detail, humanity has outgrown the planet, risking the collapse of everything.

So, how do I know what I do is helping to avoid catastrophe? Or is it adding to the misery?

Maybe what I need is a target.

For example, I could improve at woodwork.

I will give it a go from preparing the timber, chiselling out a few ragged joints, to hours sanding down the project, only to wait another two weeks while multiple coats of varnish dry.

This process takes too long for me, so shortcuts are taken, and I end up with a shoddy job.

Even if I could practice hard to learn the skills, I would need the patience of a craftsman. But I can follow the process to a result, and in this, I gain something. Various wooden items my hand has touched are scattered throughout the house—I dare not say crafted.

What I do find in this process is a near-constant feeling of gratitude.

I am grateful to the tree and to the foresters who tended it. I am warmed by the ingenuity of engineering the tools and the generations of woodworkers who have completed the trials and learnt from the errors—YouTube hosts dozens of them.

Gratitude requires awareness, which is a good path—feeling grateful means you are on it.

I could set myself a target. I want to make a passable bedside cabinet that requires mastering a few dovetails and precision cutting.

There is a good chance I will miss such a target. I simply do not have the skills and experience to make furniture.

The Problem with Target-Setting

This one is not in the self-help books, but bear with me.

Global uncertainty leaking into everyday lives is a symptom of a critical phase for humanity. Human numbers are vast, and our activities have bent the planet out of shape.

One response to this is to set an agenda of bending it back. For example, we might set a target of saving a species from extinction. However, this is a spurious target because there is a good chance that most species we're trying to save will not survive.

We fail to meet the target and set another one.

Soga & Gaston (2107) describe a form of mission creep that is just one of the problems with target setting.

Shifting baseline syndrome (SBS) is a psychological and sociological phenomenon whereby each new human generation accepts as natural or normal the situation in which it was raised. With ongoing local, regional and global deterioration in the natural environment, this results in a continued lowering of people's accepted norms for these environmental conditions.

Soga, M., & Gaston, K. J. (2018). Shifting baseline syndrome: causes, consequences, and implications. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 16(4), 222-230.

Shifting baselines are a huge problem when the trend is negative. As we progress, the concept of degradation becomes increasingly diluted, resulting in lower and lower standards being accepted as the norm for habitat conditions.

But there is more to this.

When the smelly stuff hits the fan, humanity will decide to prioritise itself over wildlife. It is what we've always done, and there is no easy way of changing that.

The best we can hope for is to shift our thinking away from targets, objectives and goals—the endpoints— and to refocus on the process itself.

Ask what we need to do to improve the planet instead of continually degrading the environment and its services.

A mindful sceptic’s solution is to focus on the process, not the target, objective, or baseline.

Rather than accepting arbitrary targets a mindful sceptic asks plenty of questions

How do we know this works?

What happens to get to a target of, let’s say, saving the koala from extinction?

What does it mean, and how will actions like planting tree species that provide food for koalas lower the chance of extinction?

How many trees are needed, and where should they be planted?

Will actions be material (proportional) to the natural dynamics of koala populations and the species?

The answers come from understanding the koala's basic ecology, context information on populations, and matching the conservation actions to these fundamentals.

All this happens before asking whether hitting a target solves the underlying problem, which is assumed to be that people value koalas and do not want to see them extinct but believe they are under threat.

Here is another example.

Suppose your local council announces a target to increase urban tree cover by 30%. Before the why question that presumably has something to do with greenspace and heat islands, a mindful sceptic will ask

What processes maintain healthy urban trees?

How does the existing tree care system work (or not work)?

What changes to current practices would support long-term tree health?

In other words, what ecological processes are relevant to trees in urban areas and can those processes support a greater number of trees?

Process-Oriented Thinking

Rehabilitating degraded soils can help restore carbon levels and, in turn, improve water retention and nutrient exchange capacities.

The target might be to sequester 1 tCO2e per hectare per annum of restored agricultural land.

But we know it's unlikely that that soil will return to anything like pre-management capabilities to hold onto carbon. Taking away the vegetation and exposing the soil pushes it toward degradation. This is hard to turn around and nearly impossible to return to prior levels unless you have several thousand years to wait for the soil to recover.

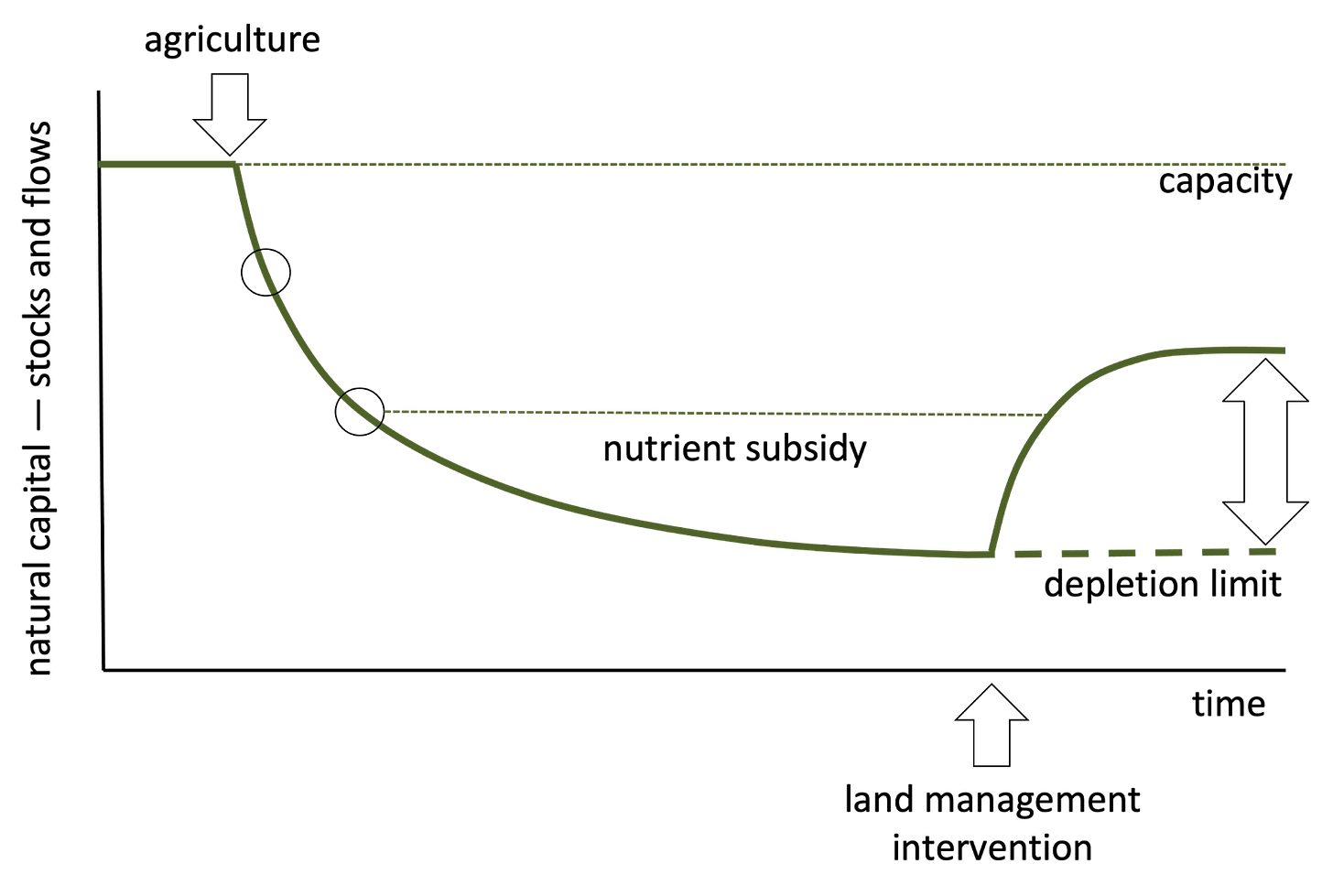

The graph for soil carbon levels after the introduction of agriculture usually looks something like this.

Rather than the 1 tCO2e ha-1 yr-1 target, the 'make a difference' thought is how the carbon is returned to the soil.

What actions must be taken, and how do they differ from current practices? This is the point of land management intervention in the graph.

The actions taken should be understood as possible directions from where we are now and move forward with awareness and understanding rather than moving forward with conventional wisdom or trying to achieve targets that can't be reached.

How do we choose the actions?

We go back to basics, the principles of how ecosystems function and how they work—we start with the fundamentals to know what is good ecology.

After the basics, we can ask more value-laden questions

What are the drivers of change in all directions?

What are the values we want from the ecosystems that we manage?

Suppose agricultural landscapes are expected to produce food and deliver ecosystem services of clean water, clean air, pollination and a range of other regulating and provisioning services. In that case, we can move that environment towards that combination without setting a target for a particular value.

We don't need water purity to be x units, soil carbon levels to be y t ha-1 or air quality to z units. We need the metrics to move positively concerning their value relative to the process.

So, yes, objectives are set but not targets—the aim would be to maintain the value, e.g. clean air, but not a fixed amount.

Here are some more examples.

One thing is clear.

Humanity cannot keep missing targets because that has a severe psychological effect on us as individuals and then as a collective. Missing targets has a profound impact on our mood, our collective performance, and our ability to make intelligent decisions.

At the extreme, we might continue to make poor decisions because why bother?

Practical Steps for a Mindful Sceptic

Make a difference by understanding ecological processes.

Again, not in the self-help books and not in the conservation manual, but it's essential. Targets are part of our psychology, but they're not helpful anymore because we act on values, not targets, even when we think they are aligned. Saving that species appears to be an admirable target; until we understand this, it is already doomed.

One of the best ways to maintain motivation and know that you are on a good path is to understand why that species is doomed.

Look at the bigger picture and the processes that allow persistence. This is about ecological thinking—more why and how than what.

So here is a way to make a difference…

Think about processes, not targets.

And here are some exercises to help cultivate that process awareness

Instead of targeting "zero waste," focus on understanding your consumption patterns

Track what you throw away for a week

Notice the systems that create waste in your life

Make incremental changes based on what you learn

Celebrate progress without getting attached to specific numbers

- Rather than pledging to ‘eat sustainably’, explore food systems

Learn where your food comes from

Understand seasonal availability in your area

Gradually shift eating habits based on this knowledge

Share insights with fellow students

Instead of setting garden biodiversity targets, enhance natural processes

Observe what already grows well in your space

Notice which insects and birds visit

Work with natural cycles rather than against them

Share your garden's journey with neighbours

Rather than targeting specific energy reductions, understand your energy use

Track daily patterns and seasonal changes

Notice which activities use the most energy

Make mindful adjustments based on observations

Mentor others in your community

Why focus on processes rather than targets

Here are three good reasons why a mindful sceptic focuses on process over targets. Because…

Environmental and social systems are complex and interconnected

Critical thinking shows us that fixed targets, however well-intentioned, often oversimplify these relationships and miss crucial interactions. A process focus gets to the mechanisms of an outcome and make it easier to recognise unexpected outcomes and understand how different parts of a system influence each other. This is why successful restoration projects often evolve their approaches over time, learning from both successes and setbacks. A process focus lets us work with the complexity rather than trying to reduce it to simple numbers or targets.

Targets tell us what we want but rarely reveal how to achieve it.

A process focus helps us understand the actual mechanisms of change—what works, what doesn't, and why. This is crucial because it reveals causal relationships and success factors we might otherwise miss. For example, when we study how successful community composting systems work rather than just setting volume targets, we learn principles we can apply elsewhere. This evidence-based understanding of ‘how’ rather than ‘what’ leads to more effective and replicable solutions.

While targets imply linear progress toward a goal, real-world change often involves cycles, setbacks, and unexpected developments.

A process focus makes it easier to notice and appreciate small but significant improvements, learn valuable lessons from apparent failures, and recognise benefits we hadn't anticipated. This way, setbacks are part of the process, not signs of failure. It's about working with nature's rhythms and human nature's complexities rather than trying to force them into artificial timelines and targets.

There are plenty more reasons.

Offer yours in the comments.

Key points

While seemingly concrete and ambitious, setting specific targets for environmental initiatives can be counterproductive. These goals frequently fail to account for the intricate, interconnected nature of ecosystems and human behavior. The rigid nature of targets can lead to short-term thinking, shifting baselines, and a sense of failure when not achieved. This approach may inadvertently hinder progress by oversimplifying complex environmental challenges.

Shifting focus from end goals to the underlying processes that shape our environment can yield more meaningful and lasting change. This approach embraces the complexity and non-linear nature of ecological systems. We can create more adaptable and sustainable solutions by understanding and improving these processes. Process-oriented thinking allows for continuous learning and adjustment, leading to more holistic and effective environmental management.

Process-oriented approaches have shown promising results across various environmental domains, from marine conservation to urban planning. These strategies prioritise long-term ecosystem health, biodiversity, and resilience over narrow, quantitative targets. By focusing on processes such as habitat connectivity, soil health, or circular economy principles, these initiatives create more comprehensive and adaptable solutions to environmental challenges.

Combining critical thinking with open-minded awareness allows for a more nuanced understanding of environmental issues. This approach encourages questioning conventional wisdom, understanding complex systems, and proposing more effective solutions. Mindful sceptics are well-positioned to navigate the complexities of current environmental challenges, offering fresh perspectives and innovative approaches to making a meaningful difference in our world.

In the next issue

Ever wondered how termites in the African savanna could teach us to spot fake news? Join me on a journey from the floodplains of the Okavango Delta to your daily social media feed as I reveal the ten essential steps that transformed me from a curious field researcher into a mindful sceptic.

Whether you're drowning in information overload or trying to separate environmental fact from fiction, these battle-tested evaluation skills might change how you see the world. And yes, those termites did bite.

Some mindful momentum

Spread the Word

If this article resonated with you, share it with three friends or colleagues who are passionate about environmental issues.

Invite them to subscribe to our newsletter and join our community of mindful sceptics. Together, we can foster a more nuanced, process-oriented approach to tackling environmental challenges.