A Graph That Upends Certainty

Why our global feast rides on invisible chemistry and borrowed ground

Historians and anyone with half an eye on the past know that the world changed when fossils made industrial energy cheap; the quiet shift from candles to crops fertilised with synthetic nitrogen set the stage for a population never seen before.

Around 1785, the British began using natural gas from coal for home and street illumination. Hard to imagine what a change it was from whale oil lamps and candles to a clean and relatively safe form of light.

In 1816, Baltimore, Maryland, became the first city in the United States to light its streets with natural gas.

Then, in 1885, Robert Bunsen invented the Bunsen burner, which could vary the amount of air mixed with the gas stream to produce a cooler or hotter reaction. Researchers could now carry out delicate procedures such as flame tests for element identification, controlled thermal reactions, and glasswork that required specific, consistent temperatures. Bunsen’s refinement turned the open flame from natural gas into a dependable scientific instrument.

As infrastructure improved, gas was piped into homes for cooking and heating, with the first gas stoves and water heaters emerging by the mid-19th century. This convenience marked a turning point in domestic life, especially in urban areas where coal smoke and soot had been major nuisances.

Industrially, natural gas became a reliable heat source for glassmaking, metalworking, and ceramics, where consistent flame temperature improved both efficiency and quality.

Once these opportunities to use gas were established, it made sense to build pipelines to maintain supply.

These were built in the 20th century.

The oil revolution happened soon after, a little over 100 years ago and almost within living memory. A retouched photograph in the Library of Congress was copyrighted in 1890, showing Edwin L. Drake in Titusville, Pennsylvania, where the first commercial well was drilled in 1859 to find oil.

As with many revolutions, the effects of these energy innovations unfolded over time.

It took time to build the infrastructure, power lines, roads, and fertiliser factories. And time to figure out how to manufacture an engine that converts coal power into rotational energy to run a cotton mill or force steam through turbines to generate electricity.

But build these things we did.

This new energy source enabled all sorts of innovations.

In 1909, German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed a high-temperature, energy-intensive process to synthesise plant-available nitrate from the air. The process converts atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) by reacting it with hydrogen (H2) in the presence of a metal catalyst at high temperatures and pressures.

The primary source of hydrogen is methane from natural gas. Approximately 60% of the natural gas is used as raw material, with the remainder employed to power the synthesis process.

Crucially, this invention was scalable.

By the 1920s, factories were producing ammonia on a commercial scale. One hundred years later, the Haber-Bosch process produces 230 million tonnes of ammonia annually (roughly 188 mt of nitrogen), mainly for use as a nitrogen fertiliser, as ammonia itself (in the form of ammonium nitrate), and as urea.

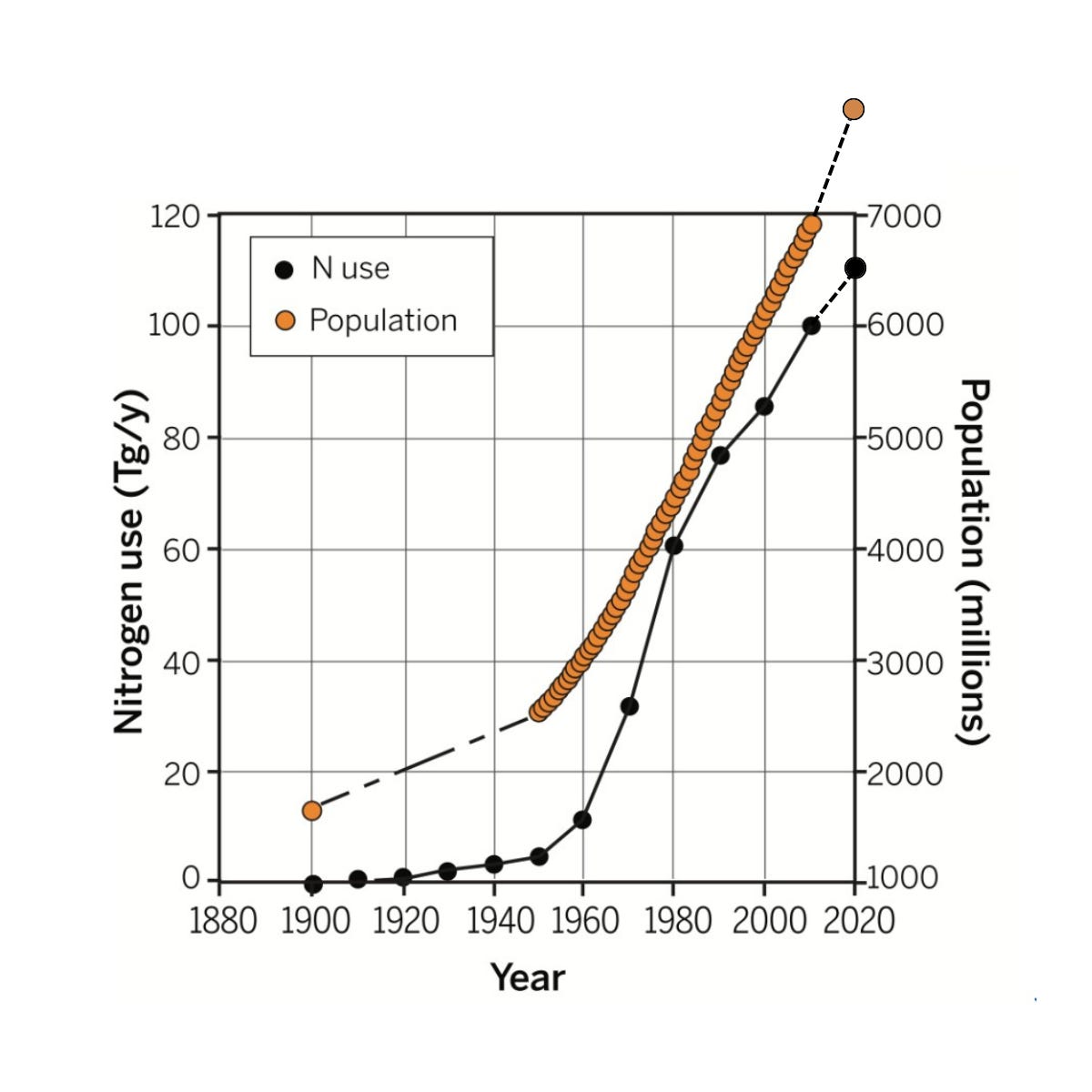

And with this historical pramble we come to the graph that explains so much.

Here it is.

It shows the rise in nitrogen fertiliser use after the invention of the Haber-Bosch process—an exponential increase in production and use.

And the parallel rise in human populations.

The growth in world population in the late 20th century mirrors the increasing use of industrially derived N fertiliser. It also follows the rise in energy use.

This correlation is not a coincidence.

Crop production would have stalled if the energy-intensive conversion of nitrogen gas to ammonia had not occurred. If average agricultural yields had stayed constant since 1900, crop harvesting in 2000 would have required roughly four times as much cropland as was actually used.

Humans ate fossil fuels, and there was so much to eat that we made plenty more humans.

We know there are now 8 billion humans on Earth, most of them arriving in the last 100 years. And we also know that numbers are increasing at a rate of roughly 8,000 per hour.

A counterfactual without nitrogen fertiliser and fossils

Suppose that we model human population dynamics under the environmental constraints typical of the early agricultural era, before the large-scale introduction of exogenous energy and industrial technology.

The plough has been invented, as has the domestication of draught animals, but the exclusion of fossil fuels and industrial fertilisers means food production stays close to the traditional, pre-industrial phase of agriculture that spanned many millennia before the Industrial Revolution.

Around 10,000 BCE, at the beginning of agriculture, modern humans (Homo sapiens) were estimated to be between 2 million and 10 million individuals. The best archaeological estimate for the global population at 10,000 BCE is 4 million.

Before this time, humans lived a primitive, primal life where hunger was ever-present, and mortality rates, especially for the young, were high.

The introduction of agriculture, which included the ability to store grain crops and the use of animal power (draught animals) and tools (the plough), provided a net energy surplus compared to gathering and hunting. This permitted modest population growth by relaxing the ecological shackles that limited hunter-gatherers.

In the absence of fossil fuels and industrial fertilisers, this period of agricultural development resulted in a population growth rate of approximately 0.04% per year, slow but exponential growth.

Population growth remained slow because agriculture was relatively inefficient compared to modern methods and societies were constrained by disease and nutritional deficits. For example, in the Middle Ages, life expectancy was only about 30 years everywhere.

If the global population started at 4 million in 10,000 BCE and grew continuously at the pre-industrial agricultural rate of 0.04% (assuming 13,000 years to 3000 CE), the population would be roughly 725 million by 3000 CE.

Therefore, under the constraints of no fossil fuels and no industrial fertilisers, the estimated human population today (c. 2025 CE) would be significantly less than 1 billion people, residing somewhere in the range of ~490 million, assuming uninterrupted 0.04% annual growth from 10,000 BCE without encountering catastrophic resource limits along the way.

It wouldn’t even make it onto the graph.

What the graph tells us

Obviously, this didn’t happen.

Instead, there was a massive increase, often referred to as the “population spike” or “Great Acceleration,” which was explicitly enabled by the factors excluded in the counterfactual.

The world changed when abundant coal made industrial energy cheap, followed by natural gas and oil. This captured exogenous energy allowed humans to turbocharge crop yield and livestock production through intensification. Fossil fuels allowed the conversion of over half the habitable land into a food factory and provided the energy for public health infrastructure.

The Haber-Bosch process became the dominant energy-intensive conversion of nitrogen gas into ammonia, preventing crop production from stalling and enabling the subsequent exponential rise in population.

So here is another counterfactual.

If average agricultural yields had stayed constant since 1900 (i.e., without industrial inputs), crop harvesting in 2000 CE would have required roughly four times as much cropland as was actually used.

This is as important an observation as the growth in nitrogen use.

0.5 ha of arable land per person

When I was born in 1961, the population was a little over 3 billion, and nitrogen use had begun to expand in volume and extent. At this time, roughly 0.5 ha of cropland per capita was available worldwide.

It turns out that 0.5 hectares (ha) of cropland per capita is the amount estimated to be needed to provide a diverse, healthy, and nutritious diet that includes both plant and animal products, similar to the typical standard of living in the United States and Europe.

Half a hectare is often cited as the land area needed to produce a nutritionally adequate diet because it reflects aggregate global averages of agricultural output, yields, diet composition (including meat), and crop/pasture land use under current farming systems.

The value incorporates several key assumptions, including that yields are moderate; that the diet includes animal products; that land is a mix of cropland and pasture; that there is some food waste; and that soil fertility/inputs are sufficient.

Crucially, this is not the minimal possible under highly optimised vegetarian diets or intensive systems, nor is it a fixed boundary. Land requirements per person vary dramatically with diet (plant-based diets reduce them), yield improvements reduce them, and local agroecological conditions influence them.

In the context of “sufficient nutrition”, it assumes a certain diet quality; a lower-quality diet might demand less land, but a higher-quality diet or more animal protein will require more.

So, the “0.5 ha per person” estimate emerges from modelling typical diets and farming systems globally and offers a useful rule of thumb, but it could be as low as 0.10 ha per person in some developing-country diets and as low as 0.03 ha per person under very efficient systems.

A recent proof-of-concept farm study of nutritional self‑sufficiency in Israel found that a single adult’s nutritional needs could be met on ~0.074 ha with a largely plant-based diet, a well-managed system, a favourable climate, and irrigation.

Either way, the lower bound of ~0.03 to 0.10 ha per person reflects very efficient, low-animal-product diets and optimised systems (high yields, low waste, favourable climate).

The more realistic “minimum viable” for a diversified diet under typical conditions may be closer to ~0.1 ha per person, assuming modest animal products, moderate inputs, and no major soil degradation or climate penalties.

So, how much land is available?

Available arable land

Global agricultural land (cropland + pasture) was approximately 4.78 billion ha in 2022, as estimated by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO).

The crude calculation of the population at the time yields 0.6 ha per person, which sounds hopeful.

However, the global “arable land (hectares per person)” indicator from the FAO, where “arable land” is defined as land under temporary crops + fallow + market/kitchen gardens, etc., was ~0.17 ha per person in 2023, down from ~0.24 ha in 2001.

In other words, the global averages are closing in on the optimistic baseline. And from two directions.

The number of people continues to increase by 8,000 per hour, and arable land continues to degrade, so the global amount of arable and productive land per person in 2050 is projected to be only a quarter of what it was in 1960.

If the current rate of arable land loss (over 12 million ha per year) is maintained, there will only be sufficient arable land to sustain a population of 2 billion people in just 42 years at the minimum viable 0.1 ha per person.

In addition to cropland, achieving a high standard of living requires allocating substantial land to other essential uses, including approximately 1.5 ha per capita for renewable energy and about 1 ha each for forest and pasture production.

But we will save those numbers for another time.

Upending certainty

Amundson et al.’s graph is powerful because it compresses 10 millennia of coevolution among soil fertility, nitrogen use, and population into a single visual, revealing how modern human security rests on a historically unprecedented—and unsustainable—acceleration of soil nutrient exploitation.

The visual integrates biophysical and demographic history.

It plots human population growth against estimated rates of nitrogen fertiliser use and soil nutrient extraction, showing that for nearly 10,000 years, human numbers and nitrogen fluxes were almost flat—both governed by natural soil fertility and biological nitrogen fixation. Then, around 1900, the Haber–Bosch process caused a dramatic departure from that long equilibrium. The resulting exponential rise in synthetic nitrogen input mirrors the population explosion, visually demonstrating the coupling of industrial nitrogen fixation to food production and global population growth.

Secondly, the figure conveys the soil–security feedback loop more clearly than tables or text could. It shows that modern societies depend on an energy-intensive, industrial nitrogen cycle to maintain soil productivity, implying that soil degradation or fertiliser shortages would reverberate through food systems and population stability.

The visual juxtaposition of population and fertiliser curves makes the dependence stark as the curves rise together, indicating that soil nutrient availability is not merely an agricultural issue but a civilizational one.

Finally, the graph translates complex Earth-system interactions into a moral and policy insight. The entire edifice of modern human security rests on soils enriched artificially beyond their natural regenerative capacity.

The Anthropocene nitrogen surge is a geological discontinuity—linking chemistry, demography, and ethics. In one frame, Amundson et al. make visible the hidden metabolic dependency that underwrites our era of abundance and exposes its fragility.

It’s a masterpiece.

Mindful Momentum

Track your nitrogen footprint for a week... Read the ingredient list on everything you eat and note which items depend on industrial fertiliser for yield. Bread, pasta, meat, dairy, and vegetables grown at scale. Count the meals that would vanish if the Haber-Bosch process stopped tomorrow.

Map your personal land requirement… See if you can calculate how much cropland your current diet demands using the 0.5 ha baseline for animal products, or 0.1 ha for an optimised plant-based system. Compare that number to the global average of 0.17 ha per person in 2023. Ask whether your consumption fits within the soil budget we have left.

Walk one hectare… Find a local park, sports field, or paddock and pace the perimeter of an area of 5,000 square metres or half a hectare. It is just shy of 100 paces on each side. Notice how small half a hectare feels when you imagine it feeding you for a year. Then walk it again and picture eight people sharing that same plot by 2050.

Key Points

Global population growth in the 20th century mirrors the exponential rise in nitrogen fertiliser use enabled by the energy-intensive Haber-Bosch process.

Without fossil fuels and industrial nitrogen, human population would likely remain below 1 billion, not 8 billion.

Arable land per person has fallen from 0.5 hectares in 1961 to 0.17 hectares in 2023, closing in on the minimum viable threshold of 0.1 hectares required for basic nutrition.

At current rates of soil degradation, sufficient arable land will support only 2 billion people within 42 years.

Curiosity Corner

This issue concerns the relationship between exogenous energy and population.

But as we usually do, we can find some better questions:

What happens to soil microbiomes when nitrogen arrives as a gas-derived liquid instead of as manure or legume roots? Synthetic fertiliser delivers readily available nitrate and ammonium that can shortcut microbial symbioses, often boosting fast-growing, copiotrophic microbes while suppressing mutualists and the slower carbon-building guilds that stabilise aggregates. Over time, that shift can reduce soil structure, humus formation, and resilience in nutrient cycling, even when yields hold steady in the short run.

How would global trade routes shift if each region could only feed the population its own soil productivity supports? Regions reliant on imported calories or fertiliser would face tighter local price loops, with diets narrowing to what regional soils and rainfall can sustain, pushing coastal cities and arid nations to renegotiate food security as logistics, not cuisine. Export power would move toward places with resilient soils and water, changing geopolitical leverage from fuel corridors to soil corridors.

Which technologies require less energy than Haber-Bosch to fix atmospheric nitrogen at scale? Emerging pathways include electrochemical nitrogen reduction, plasma fixation, and biological enhancement strategies, each promising lower-temperature routes but struggling with rate, selectivity, and real-world deployment beyond pilot scales. The open question is not lab feasibility but whether any route can beat today’s gas-fed thermodynamics at farm-gate cost without shifting burdens to the grid or land.

What percentage of modern pharmaceuticals, plastics, and infrastructure depend on the same natural gas feedstock used to make ammonia? Natural gas is both fuel and feedstock across ammonia, methanol, polymers, and many precursor chemicals, so disentangling nitrogen fertiliser from the broader gas economy exposes shared fragilities in price spikes and supply shocks. Counting dependencies clarifies that fertiliser reform is a whole-chemistry project, not a single-product swap.

If the graph were redrawn with topsoil depth instead of nitrogen use, would the curve run in the opposite direction? Topsoil depth trends are local and lagged, but many intensively farmed regions show thinning A horizons and compaction that erode buffer capacity against drought and flood even as inputs rise. Swapping axes tests whether our abundance story rests on a diminishing layer, which reframes yield as a drawdown of structure rather than a permanent gain.

Evidence Support

A few peer-reviewed papers relevant to the topic were selected from the vast array of options. Science knows a lot about this topic.

Amundson, R., Berhe, A. A., Hopmans, J. W., Olson, C., Sztein, A. E., & Sparks, D. L. (2015). Soil and human security in the 21st century. Science, 348(6235), 1261071.

TL;DR... synthesises evidence that soils underpin food, water, climate regulation, and biodiversity, while facing accelerating pressures from erosion, nutrient imbalance, sealing, contamination, and climate change that outpace natural soil formation in many regions. It argues that safeguarding soil functions is a prerequisite for human security and outlines policy, monitoring, and management priorities to arrest degradation and rebuild soil capital.

Relevance to post... grounds the claim that land is the binding constraint by showing soils as a slow‑forming, fast‑losing asset whose degradation narrows feasible diets and yields even when inputs rise, directly linking to the post’s warning about shrinking per‑capita arable capacity. It provides a rigorous framework for translating a vivid graph into system risk by tying biophysical limits to food availability over human time scales.

Erisman, J. W., Sutton, M. A., Galloway, J., Klimont, Z., & Winiwarter, W. (2008). How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nature Geoscience, 1(10), 636–639.

TL;DR... documents how Haber–Bosch nitrogen underpins a large share of current food production and population, framing reactive nitrogen as the key determinant of twentieth‑century yield gains and the modern nitrogen cascade. It highlights the coupled benefits and externalities of synthetic fertiliser, including eutrophication, air pollution, and nitrous oxide emissions.

Relevance to post... central linkage between synthetic nitrogen and population dynamics, and explains why the food system’s apparent abundance is contingent on energy‑intensive ammonia, not just better agronomy. It also sets up the mindful sceptic move by showing that the same molecule that feeds billions degrades water and the climate, sharpening the question of acceptable nitrogen pathways.

Galloway, J. N., Townsend, A. R., Erisman, J. W., Bekunda, M., Cai, Z., Freney, J. R., ... & Sutton, M. A. (2008). Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: Recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science, 320(5878), 889–892.

TL;DR... global review quantifies the human‑driven creation of reactive nitrogen, showing steep increases from fertiliser manufacture, fossil fuel combustion, and the cultivation of nitrogen‑fixing crops, and tracks how that nitrogen propagates through air, land, and water as a cascading set of impacts. It also evaluates solution levers across efficiency and precision applications to diet and policy, noting the scale of reductions needed to lower damage without collapsing yields.

Relevance to post... reinforces the post’s claim that twentieth‑century food output and population growth mirror reactive nitrogen’s rise, while clarifying that the system hangs on a narrow efficiency margin, not on limitless substitution. The paper provides credible mechanisms linking fertiliser dependency to ecological costs, which is essential for arguing that the graph is not merely a correlation but a system structure.

Foley, J. A., Ramankutty, N., Brauman, K. A., Cassidy, E. S., Gerber, J. S., Johnston, M., ... & Zaks, D. P. M. (2011). Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature, 478(7369), 337–342.

TL;DR... halting cropland expansion, closing yield gaps, improving input efficiency, shifting diets, and cutting waste could substantially increase food supply while shrinking environmental footprints, synthesising spatial data on yields, land, water, and nutrients. The analysis frames land use and nitrogen use as joint constraints that must be solved together to avoid pushing agriculture across planetary boundaries.

Relevance to post... underwrites the post’s point that per‑capita arable land is tightening and that the remaining headroom depends on efficiency and diet rather than expansion, which validates the exercises on land budgeting and dietary footprints. It also provides a plan‑level map that connects the graph’s story to practical system levers a mindful sceptic can evaluate without hype.

Ausubel, J. H., Wernick, I. K., & Waggoner, P. E. (2013). Peak farmland and the prospect for land sparing. Population and Development Review, 38, 221–242.

TL;DR... evidence that cropland per capita has declined for decades and argue that yield growth and dietary shifts can enable absolute land sparing, potentially reducing the total area of farmland even as populations grow and diets improve in aggregate. They synthesise global land-use and yield series to demonstrate the feasibility and conditions for achieving peak farmland without sacrificing caloric supply.

Relevance to post... arable land per person has compressed toward tight thresholds, while also showing that the direction of travel is not fated if yield gaps and diet composition are addressed, which sharpens the piece’s hinge between alarm and agency. It equips readers to interrogate whether current efficiency gains are real land sparing or accounting artefacts, aligning with the newsletter’s sceptical posture toward simple optimism.

In the next issue

Three per cent of your body is nitrogen, and half of it came from a machine, not microbes.

Next week, we follow the fertiliser link to population into the ground to see what happens when the living foundation of food turns into a substrate we ignore.

"Before this time, humans lived a primitive, primal life where hunger was ever-present, and mortality rates, especially for the young, were high."

I don't think this is true. As "Civilized to Death" explains, a hunter-gatherer life didn't have much hunger, if any. There was abundant food for us clever humans. Perhaps only when migrating to very different environments did those humans sometimes experience difficult periods. Of course, childhood and birth mortality would have been far higher than today, but those who made it to adulthood could expect to live to 60 or 70 years, sometimes longer.

If hunger were ever present, it's doubtful our species would have survived very long.